ALT Conference – Siân Bayne – Wednesday 6th September 2017

www.chrisbullphotographer.com

pictures@chrisbullphotographer.com

Digital information gathering is everywhere – it’s collection is hidden behind the T and C check box for every platform registration, and is gathered when students use their Virtual Learning Environments. There’s an assumption that having student information is a good thing; we just need to work out what to do with it. Several thought provoking sessions at the Association for Learning Technologists Conference 2017 brought up different perspectives around this theme – the role of anonymity in learning, potential uses of learner analytics, what students think we do with learning analytics, and the parallel with platform capitalist collection and use of data and consequent filter bubbles.

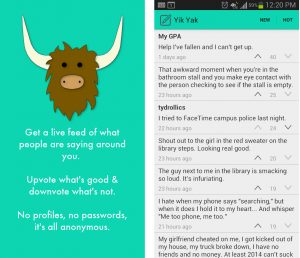

Example of social media Yik Yak, from: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/cyberbully-app-yik-yak-banned-uk-schools-1448007 [accessed: 08/09/17]

The social media app Yik Yak demonstrated a need for anonymity within learning. Siân Bayne, during her key note at ALT-C 2017, described Yik Yak as a social media tool that allowed people within a restricted radius to communicate – focusing on hyperlocality and anonymity. Yik Yak become both popular across the US and UK with students due to intensive marketing, but also notorious in the media for hate speech and victimisation. However, research by Saveski, Chou and Roy (2016) suggested that community moderation was effectively up-voting positive yaks, while down-voting negative yaks, and vulgarity was comparable to twitter. Students would share information, talk about missing lectures, sex/dating, and emotional wellbeing – Yik Yak, in some ways, had developed into a personal support network. This was until August 2016, when designers switched their focus away from anonymity, which was thought to contribute to negative behaviours, to instead require participants to create profiles. Bayne’s data show a HUGE drop in usage when anonymity was removed, which partly recovered when designers brought it back. Sadly, in May 2017 the app closed – largely due to the measures brought in to combat victimisation. Thus, Siân argued, there is a role for anonymity in discussion spaces.

At the same time, there is a great deal of interest in collecting and using learning analytics. A wealth of data is collected about our students including demographics, assessment scores, attendance, usage of virtual learning environments such as Blackboard, Canvas or Moodle, access of learning activities and lecture recordings. Laraine D’antin of Southampton Solent University suggested that data analytics should be used both during curricular redevelopment to better tailor the approaches toward students and also as a student dashboard to help students become more self-aware of their role in learning. Their approach to the latter involved drawing links to other forms of data collection and profiling, that students may be aware of, such as companies like Amazon and Facebook, and tools such as Fitbits. Laraine felt that students generally didn’t have reservations about their data being used in this way, and in fact, expected that it was already shared across the University. Interestingly, they wanted equivalent data about staff and teaching – such as how many students passed the course in the previous year, and metrics on the quality of the teaching. Samantha Ahern, from University College London, further suggested that given the rise and prevalence of mental difficulties experienced by students – one stat suggesting that 78% of students thought they had a mental health issue that year – perhaps behavioural patterns associated with mental issues could be detected by using learning analytics. These might include detecting changes in behaviour seen as reduction in grades, missing deadlines or increasingly frequent absences, which in combination with other behaviours such as dropping extracurricular activities, substance misuse, isolation and withdrawal, lack of self-care, and extreme risky behaviours might suggest a struggling student. She was quick to point out that whilst the Universities UK Framework on mental health #stepchange suggests we should promote a compassionate culture, and align learning analytics with student wellbeing, there are also big challenges – mental illness, as a disability, falling under a protected characteristic within the UK data protection law, and potential liabilities exist should students fall through the gaps.

ALT Conference – Day Three – Thursday 7th September 2017

www.chrisbullphotographer.com

pictures@chrisbullphotographer.com

One approach to the question of what to do with learning analytics, might be to ask students themselves – Alex Whitelock-Wainwright described development of a psychological survey tool to assess student’s expectations of learning analytics. The instrument has been refined to 12 items based on student feedback and factor analysis, which fall into two areas – ethical expectations around consent for usage, and service expectations around how staff will act. The questionnaire has been validated at the University of Liverpool, and is currently being considered by groups across Europe.

The use of learning analytics, as pointed about by Laraine D’antin, has parallels with the information profiles that some of the big internet companies are collecting on us. Siân Bayne quoted Lanchester (2017) that “Facebook, in fact, is the biggest surveillance-based enterprise in the history of mankind”, further suggesting that when the service is free, it is in fact, users or their data profiles, that are the products being traded. Now, Bayne suggests, data is the new oil, and platform capitalism depends on a platform’s ability to extract and use our personal data. Resistance to collection of data can occur through use of anonymous apps, such as Yik Yak. However these types of apps are less likely to last, as they do not generate wealth through selling data, and their anonymity causes moral panic around its perceived dangers.

For what are companies collecting our data? Perhaps it is to tailor information, adverts and services to our profiles – creating “filter bubbles” – where the information that is presented to us as passive users, is filtered based on our profiles. Whilst there are emotional benefits to only being given that we might find interesting or reinforcing, or opinions that we are comfortable with, there are also risks. Kamakshi Rajagopal from the Open Universiteit in the Netherlands ran an insightful workshop, allowing participants to explore the idea of a filter bubble and how restricting the people, sources and perspectives that are available to us will limit our learning and criticality. One approach to resisting this, as both Kamaksi and Siân pointed out, is the use of anonymity to prevent data collecting, profiling and therefore restricted perspectives.

It also raises the question – will learning analytics create filter bubbles if we target certain information, advice and support or services to students based on their learner profiles? What would this mean for their learning?

Just to prove I was there, and yes, listening.

References:

Lanchester, J. (2017). You Are the Product. [Review of the books The Attention Merchants: From the Daily Newspaper to Social Media, How Our Time and Attention Is Harvested and Sold, Chaos Monkeys: Inside the Silicon Valley Money Machine and Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google and Amazon have Cornered Culture and What It Means for All of Us.] London Review of Books, 39(16), 3-10. Retrieved from https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n16/john-lanchester/you-are-the-product.

Saveski, M., Chou, S., & Roy, D. (2016, March). Tracking the Yak: An Empirical Study of Yik Yak. In ICWSM (pp. 671-674).

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Great post. We’re (HE) about to shoot ourselves in the foot again by intrusive neoliberal use of learning alanytics, driving students underground and loosing the major benefits.