As part of the ‘Implementing lecture capture – what are we learning‘ event on Monday 11 September 2017, we held discussions on the theme of Pedagogy, Practice and Policy.

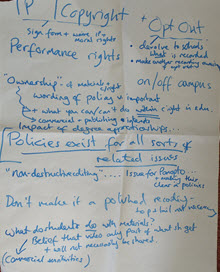

The Pedagogy, Practice and Policy discussions started by considering institutional policy and whether the use of lecture capture is on an opt-in or opt-out basis. We also discussed different ways of managing the conversation over staff performance rights and the need for greater understanding of the implications of copyright and commercial sensitivity in recordings. For students opting out, recordings can be paused or edited later. However if the lecture capture system has ‘non-destructive editing’, then the recording still exists in cloud storage even if it is edited out.

For the second part of the discussion, we covered the hot topics of student attendance and engagement. King’s College shared research by one of their academics that showed that lecture capture had adversely affected attendance at lectures and that those not attending performed more poorly. However there are many reasons for non-attendance, of which lecture capture is only one. With the impact of fees and the need for students to earn money, students want to learn more flexibly. There is also a need to make the experience of attending a teaching session more valuable, for example by including activities that will not be included in recordings or the use of flipped classroom teaching.

It was generally agreed that students need guidance on how to use recordings to effectively support their learning. Appropriate learning analytics may be useful in analysing engagement before, during and after classes.

Details of the Pedagogy, Practice and Policy Discussion

Details of the Pedagogy, Practice and Policy Discussion

Policy: Opt in vs Opt out

We started with discussions on Policy: Opt in vs Opt out. Institutions will usually already have policies for many aspects of lecture capture, for example Intellectual Property and Performance Rights. However in some cases the introduction of lecture capture highlights existing issues; for example, the copyright of teaching materials does belong to the university, but academics weren’t necessarily aware of this until it was highlighted by lecture capture.

The specific wording of the policy is important and takes time to agree. The details will vary between institutions, depending on what other policies are in place and what is included in staff contracts and student regulations.

Two examples of policy from different institutions were:

- Opt-out, but the decision about what to publish is devolved down to Schools and Departments. This provides the ability to tailor usage to different practices and disciplines.

- Opt-out, but with the ability to put another recording up in place of the actual live recording. This gives academics more control.

Performance and rights and Copyright were areas of much discussion and some confusion. One institution had been advised that academics need to sign a form to waive both performance rights and moral rights. Another way to handle this issue it to write it into the policy: if you use the service, you are waiving your rights. If you opt out, you preserve whatever rights are not covered by other existing policies. Also there may be a difference between performance rights on- and off-campus, but this is unclear.

At Sheffield University, the university owns the copyright but the academic owns the performance rights. If the institution wants to reuse a recording then the academic has to give permission. This still applies if the academic has left the institution.

In some disciplines there are also issues of commercial sensitivity, particularly for students on degree apprenticeships who may bring in materials from their placements.

Lecturers need to know when they are able to use images and other materials, as there are exceptions for educational purposes. There is a lot of confusion around this.

Other discussions were on how students use recordings. Several people felt that students were used to skipping through videos to find relevant sections, so there was no need to ‘top and tail’ to produce a polished recording.

Prior to lecture capture, staff frequently expressed concern about the illicit sharing of recordings by students. However this seems to be uncommon and will usually be covered by existing regulations. A student at the event didn’t feel most students would have time to do this, even if they wanted to.

Some institutions had issues with ‘non-destructive editing’ (for example in Panopto), which means that recorded content still exists in cloud storage even if it is edited out. Although the material does exist, it is not published and thus not available to viewers. However if this still causes problems, you can choose to actually stop a recording while discussions are taking place and then start a new recording later.

However there can be a conflict between the need for a usable system and data privacy. This applies to many systems other than lecture capture, for example you could potentially track student movements using the university wi-fi.

Pedagogy and Practice: student attendance and engagement

For the second half of the session, discussion focused on the hot topics of student attendance and engagement.

Attendance

An academic at King’s College recorded attendance before and after the introduction of lecture capture and found that attendance plummeted. They analysed attendance, viewings and performance and found that a student who hadn’t attended a lecture had to watch recordings five times to gain the same results as someone who had attended the lecture. This subject was in Politics (teaching research methods). It may highlight the need to educate students on how to use recordings.

Small scale research at Leicester shows no correlation between the use of recordings and achievement, but this area needs more research.

Lecture capture isn’t the only thing that affects attendance. Is it just the latest reasons why students don’t attend? It is a complicated picture, with the changing demographic of students and the need for paid work. There are many reasons for non-attendance.

With the impact of fees and the need to earn money, students want to learn more flexibly. If attendance is dropping, we need to think about why that is? There is a need to evaluate teaching and offer students different ways to engage and learn, for example a combination of online and face-to-face, or flipped classroom. Also students attending a lecture might not mean that much in terms of engagement.

A delegate from Oxford University felt that students who don’t turn up might not turn up anyway. He has used previous recordings in flipped classroom model and found that attendance at the face-to-face sessions was much higher than at traditional lectures. This raises the question of when does a lecture become a seminar? This lecturer calls them ‘teaching sessions’ rather than using the traditional terms.

We need to recognise the impact of non-attendance on students who do attend.

Making lectures more valuable

It was felt that face-to-face sessions have richer quality than recordings.

We need to consider how to make lectures more valuable for students. For example one lecturer at the University of Kent has a five minute discussion at start of a Finance session linked to current affairs which isn’t recorded, so those missing the lecture won’t hear it. This provides a reason to attend.

In some cases, students are acting as consumers and working out how much it costs them per lecture. They may feel they need to attend the lecture rather than just watch the recording in order to get value for money. There are different perceptions of value: academic perspective vs commercial perspective. The quality of lecture affects the perception of value.

Engagement

What does engagement mean? For example a lecturer in a very large lecture thought they had engaged well with the group of students, but actually only two students took part in the discussion.

How students use videos is important: watching the videos isn’t a replacement for revision. The recordings are there to support learning, not as the only source of information.

Students reported that lecture capture helps them to take notes. Has the problem been that students have previously had problems understanding how to take notes but this only became apparent when lecture capture was evaluated?

Learning analytics before and after class and in class will be useful in this area. What data can be useful for instructors?

Subscribe to Catherine Leyland's posts

Subscribe to Catherine Leyland's posts

[…] Pedagogy, Practice and Policy […]