‘The Snow Garden’, P. H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, ‘Marsh Leaves’, (London, 1895), pl. XII, SCM 08575. University of Leicester Special Collections.

‘Next to printing, photography is the greatest weapon given to mankind for his intellectual advancement,’1 Peter Henry Emerson wrote in Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, first published in 1889. This book, described at the time as ‘a bombshell dropped in the midst of a tea party’2, passionately argued that photography should be ‘naturalistic’, a faithful representation of the world around us, not an imitation of another art form. Emerson scorned the practice of combining multiple images and never retouched his photographs. He believed that a photograph should accurately reproduce what the human eye saw, and strove to replicate the effect of peripheral vision by contrasting sharp focus on particular objects with a ‘misty’ effect for the rest.

In addition to Naturalistic Photography …, the University is very fortunate to possess a

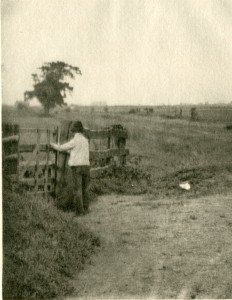

‘A Corner of the Farmyard’, P. H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, ‘Marsh Leaves’, (London, 1895), pl. XIII, SCM 08575. University of Leicester Special Collections.

copy of Emerson’s Marsh Leaves, his final book of photography, considered by many to be his best. This came to us courtesy of the extraordinary Thomas Hatton (boot manufacturer, book collector, promoter of boxing and greyhound racing, founder of a crossword puzzle company and authority on Charles Dickens – more about that in a later blog post!). The photogravure process, very similar to that used in aquatint printmaking, was used to produce the plates in Marsh Leaves. The influence on Emerson of Japanese art, Hokusai in particular, is plain. Emerson was a friend of the painter, James McNeill Whistler and the misty quality of the photos is reminiscent of Whistler’s style.

Like Hatton, Emerson had a remarkable life. He was born in Cuba, but the family moved

‘The Misty River’, P. H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, ‘Marsh Leaves’, (London, 1895), pl. VIII, SCM 08575. University of Leicester Special Collections.

to England when he was of school age. He excelled at nearly everything he turned his hand to – as a scholar, a doctor of medicine, a naturalist and ornithologist, an author, an athlete in football and rowing and even in billiards. When researching for his books on East Anglia, Emerson lived among the country people, rising at dawn, shooting, fishing and sailing, exploring the fens in his horse-drawn cart with his fox terrier for company, doctoring small injuries and, most importantly, asking endless questions about their lives. His aim was to produce ‘truthful pictures of East Anglian Peasant and Fisherfolk Life, and of the landscape in which such life is lived’3, warts and all – in contrast to the sentimentalised view of rustic life often purveyed by his contemporaries. Some of the anecdotes in Marsh Leaves (for example, the fate of marsh cats, which ‘poached’ rabbits and hares, or of rats in the farmyard) are hard for modern sensibilities to take, but have to be seen in the context of a life where even women and children could be whipped by the farmer for minor misdemeanours, hunger and squalid living conditions were commonplace and the workhouse always threatened.

‘Rime Crystals’, P. H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, ‘Marsh Leaves’, (London, 1895), pl. XIV, SCM 08575. University of Leicester Special Collections.

In 1891 Emerson published The Death of Naturalistic Photography, a pamphlet printed

‘The Last Gate’, which was the final plate in Emerson’s last book of photographs: P. H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, ‘Marsh Leaves’, (London, 1895), pl. XVI, SCM 08575. University of Leicester Special Collections.

with a black border and the heading ‘Epitaph: in Memory of Naturalistic Photography’, renouncing his claim that photography was an art. ‘The limitations of photography are so great that … the medium must rank … lower than any graphic art, for the individuality of the artist is cramped, in short it can hardly show itself,’ 4 he wrote. Despite this declaration, Marsh Leaves, ‘the most exquisite and last of his albums’5 appeared in 1895. ‘Emerson was a photographic revolutionary … a protean person; a mover and shaker – Victorian in the manner that made fortunes, empires and discoveries.’6

1P.H. (Peter Henry) Emerson, Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, (London, 1890), pp. 7-8, SCM 06071

2R. Child Bayley, see Nancy Newhall, P.H. Emerson: The Fight for Photography as a Fine Art, (Aperture, 1975), p. 62, 779.092 EME/NEW

3From the preface to Pictures of Life in East Anglia, see Nancy Newhall, P.H. Emerson: The Fight for Photography as a Fine Art, (New York, 1978), p. 50, 779.092 EME/NEW

Nancy Newhall, P.H. Emerson: The Fight for Photography as a Fine Art, (New York, 1978), 4p. 93 & 5p. 103, 779.092 EME/NEW

6Peter Turner, ‘Emerson, Peter Henry (1856-1936)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004), http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38592

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments