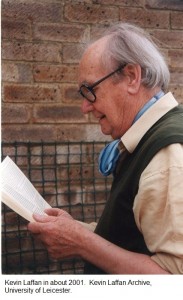

‘God alone knows why I keep trying to get a play on. I must be out of my mind, for I’m even toying with the idea of a new one! I know I’ll be wasting time and effort but I can’t get it out of my mind,’ Kevin Laffan wrote in about 2001, when he was approaching the age of 80.

While working on the Kevin Laffan Archive, I came across some partly autobiographical reflections from which this quote is taken, called ‘Memoirs of an Opsimath’ (someone who begins to learn or study only late in life), on his plans for a new play ‘about the end of the world’ to be titled Fred Noah – the play was never finished.

Kevin Barry Laffan was probably best known as the creator, in 1972, of Emmerdale Farm, the Yorkshire TV soap opera, for which he wrote 262 episodes, but his first love was the theatre and he saw himself as ‘a playwright at heart’. The narrative of Laffan’s early life was arresting. From a devout Irish Roman Catholic family, he was the third of 14 children. His father, a disabled itinerant photographer, was unable to support the family and they were eventually evicted. At the age of 12, Laffan jumped from the bailiff’s lorry carrying them through the gates of a workhouse in Walsall and ran off. Here, in his own words, is the story of how his infatuation with the theatre began:

In those days the hangabouts of society used to hang about local library reading rooms, trying to get over their own misery by reading about other people’s in the newspapers … After a day or two sleeping rough, mainly in an old disused lavatory, I needed a bit of warmth so I joined them and got myself introduced to The Stage … the rag of the acting profession … the only paper being unread when I entered the reading room. You could say, no I will say, it was the turning point of my life … I read it and became an actor.

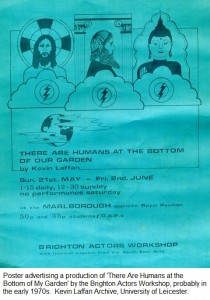

Poster advertising a production of ‘There Are Humans at the Bottom of My Garden’ by the Brighton Actors Workshop, probably in the early 1970s. Kevin Laffan Archive, University of Leicester.

He was befriended by a ‘good old biddy, who let me sleep on the sofa in her kitchen’ and managed to find a job as a gardener’s boy in a rose nursery. One day, he saw an ad in The Stage for an Assistant Stage Manager at a local repertory company, ‘experience not needed’. He ‘hadn’t the faintest idea what an ASM was but … had an enquiring mind and went off enquiring’. From these modest beginnings, Laffan went on to become artistic director of the Everyman Theatre in Reading, leaving in 1958 to concentrate on his writing.

Initially, it was a struggle; his play Cut in Ebony won an ATV award in 1959, but was never produced, because it dealt with issues surrounding race and colour and was thought to be too controversial. His first major success was Zoo, Zoo Widdershins Zoo, which won an NUS award for best new drama. In 1970, It’s a Two-Foot-Six-Inches-Above-the-Ground World had a successful run in the West End and was later made into a film, The Love Ban. As a result of his childhood experiences, Laffan was strongly critical of the Catholic Church’s stance on birth control and this was a recurring theme in his work.

Laffan was always hunting for good pseudonyms. Going through the archive, I’ve come across 9 so far. This habit generated a lot of publicity for The Superannuated Man, which won the Irish Life Drama Award in 1968 and was staged under the pen-name of Michael McNamara. ‘The theatre world is trying to solve a classic whodunit,’ wrote Matt Johnson in The Irish Sun (3 April 1997). ‘For the identity of the Irish playwright taking London by storm remains a mystery. Publicity-shy Michael McNamara … from Limerick has refused to meet the director and cast.’ Laffan also revised his work repeatedly and meticulously and often changed the titles of his plays several times.

Early notes and ideas for the play ‘Children of Cain’, also known as ‘The Naked Gael’. ©Estate of Kevin Laffan.

The archive is still in the process of being catalogued, but its contents can be viewed by arrangement in the Library’s Special Collections.

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Thanks for an informative, detailed and well-structured article.

Andrea