It was with great sadness that we learned last week of the death of one of our depositors, Sue Townsend, the creator of the Adrian Mole diaries and one of the most popular British novelists of the late twentieth century. Her work was read not just in the UK but across the world. When I showed a group of visiting international students around Special Collections in 2012 they all knew Sue Townsend’s books, and most of them had read Adrian Mole.

Sue Townsend visiting Special Collections in 2008 after receiving her Distinguished Honorary Fellowship of the University.

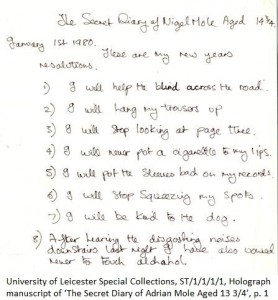

When I came to Leicester in September 2012 one of the things that excited me about my new job was that the University holds the Sue Townsend Archive. In 2005 Sue deposited her literary and personal papers with Special Collections in the Library. The archive tells the stories behind the books: where the ideas came from, how they evolved and how they were received. It also provides insights into Sue Townsend’s working methods, her personality and sense of humour. One of the Library’s most prized items is a large pile of loose sheets of paper, mainly A4 size but some smaller. They contain the manuscript of the first of two books that made Townsend the best selling novelist of the 1980s: The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole 13 3/4.

On the opening pages Adrian is actually Nigel Mole, aged 14 3/4. Methuen, the book’s publisher, insisted on the name change on the grounds that Nigel was too reminiscent of Nigel Molesworth from the series of books by Geoffrey Willans. Reluctantly, Sue acquiesced although the name change involved a great deal of deliberation. A single sheet of A4 paper in the archive contains a list of the names considered, split into three columns. The third column contains just one name, written twice in capitals: “ADRIAN / ADRIAN”.

Elsewhere in the archive are papers relating to The Queen and I, in which the monarchy has been abolished and the royal family removed to a council estate. This was not the book that Townsend was originally commissioned to write. An American publisher had asked for a biography of the Queen, which was to be written from the perspective of the author herself who was a child at the time of the coronation. Sue soon realised that this wasn’t the book she wanted to write, and so the idea morphed into a novel. Among the papers are some estate agent’s details for a 3 bedroom semi in Braunstone adorned with handwritten notes. This was the basis for the house to which the Queen and Prince Philip were removed. Someone no doubt lives there now, oblivious to their home’s place in literature. A hand drawn sketch of Hell (later Hellebore) Close shows the plan of the road and the location of the deposed monarch’s neighbours.

The archive is full of fascinating insights into Sue Townsend’s working methods, and provides a case study of how books are written and published. It offers great opportunities for student projects, dissertations and PhD theses. It is a great asset for the University, and we are fortunate that she chose to deposit it with us. The archive can be searched via the Library catalogue by selecting Sue Townsend Collection from the list of collections. Files can be consulted in the Special Collections reading room by staff, students and members of the public.

Our thoughts and sympathies are with Sue’s family at this time.

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Recent Comments