I have very recently discovered the wonder that is Scoop-it. This e-tool should supposedly save me the job of searching online to find any latest news/posts/pieces about learning outcomes in higher education (click here to check out my ‘Learning Outcomes’ scoop-it). So far it is doing a grand job and it was through my Scoop-it’s daily curation that I came across this blog piece from Gardner Campbell called Understanding and Learning Outcomes. It is quite a lengthy piece that is most decidely against the development of a learning outcomes approach in higher education. Some key extracts will illustrate his arguments against learning outcomes:

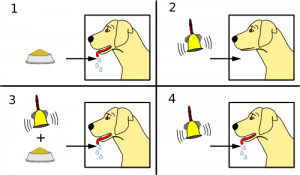

Behaviourism:

As we seek to perfect the language and institutionalization of a culture of “learning outcomes,” it seems we are necessarily moving toward a strictly behaviorist paradigm of learning, away from what Jerome Bruner refers to as the “cognitive turn” in learning theory and ever more deliberately toward a stimulus-response paradigm of learning.

Linear learning:

I see these examples and admonitions everywhere. Students will … students will … students will … students will. (Meantime the students’ will becomes defined for them, or ignored, or crushed.) Each of the above [learning outcome] statements assume a linear, non-paradoxical, cleanly defined world. The sun shines. Experience is orderly. Tab A goes into Slot B. Problem solved.

Measurable verbs:

it turns out that two of the words we must never, ever use are “understand” and “appreciate.” These are vague words, we are told. Instead, we must use specific words like “describe,” “formulate,” “evaluate,” “identify,” and so forth. You know, action verbs that we believe we can measure with confidence.

These arguments are not necessarily new – I’ve commented on similar ones in previous posts and anyone acquainted with the topic of learning outcomes will surely have come across them before. But, as I was reading the piece I was unsatisfied with some of the key arguments being made and I would like to use this space here to critique them a bit further.

(Image from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palov’s_dog_conditioning.svg)

Top of my list is Gardner Campbell’s argument that learning outcomes reinforce a behaviourist framework of learning. I find this view a very limited one. Learning outcomes can focus on a range of skills and capabilities. Some of these may be behavioural, e.g. use a computer program sufficiently, but most will be cognitively-based, e.g. critically evaluate the arguments supporting the implementation of an intervention/policy change etc etc. Far from being reductionist, learning outcomes that focus on cognitive skills/capabilities have the inherent potential to be open-ended and flexible – in other words, to be achieved in ways unique and meaningful to the learner. The learning outcome does not specify what answers must be reached or what conclusions should be drawn – this is down to the learner and the way that they approach the topic/content being studied. Biggs makes a similar point in a recent paper about the inherent potential for learning outcomes to lead to unintended outcomes as well:

at an advanced level appropriate verbs [for learning outcomes] would include “hypothesize”, “reflect”, “apply to unseen domains or problems”. These higher order LOs require open ended tasks, allowing for unintended outcomes.

…In the design of LOs and assessment tasks [teachers] are free to use open ended verbs such as “design”, “create”, “hypothesise”, “reflect” and so on. Assessment tasks should also allow for students to present their own evidence that they have achieved the criteria in openended formats…Such a design for teaching and assessment is hardly predetermined or rigid.

I would also thoroughly recommend reading Prof Jo Allan’s insightful PhD thesis on the topic of learning outcomes (or at least the second chapter which explores the theoretical perspectives concerning learning outcomes) as it locates the development of the learning outcomes concept within a much broader and enlightened educational framework than simply behaviourism.

So overall, the behaviourist stimulus/response theory seems to me inadequate and too reductionist about the concept of learning outcomes. And there is one further thing that I just can’t get away from – surely every teacher must have implicit ideas about what they want their students to get out of the course or module they are doing. And these ideas might not necessarily just focus on knowledge of content but on ways of thinking too. So why not tell the students these ideas because isn’t this essentially what learning outcomes are? Learning outcomes don’t by themselves inculcate a behaviourist framework or paradigm of learning – only not-so-good teachers would do that. Within a learning outcomes approach, a teacher can still be pedagogically creative and innovative – the only focus is on ensuring that the learning activities align to and help students to achieve the learning outcomes. And this focus seems hard to argue against – essentially, that the teaching should be geared towards enabling students to achieve what the teacher wants them to get from the module or the course (and remember, it is the teacher who writes the learning outcomes so the teacher is straightjacketed or constrained behaviouristically by their learning outcomes only if they choose to be).

But this focus on learning outcome achievement does not mean that ‘complexity and the emergent phenomena springing from it’ is outlawed. I would argue that these elements are an essential part (and outcome) of engaging in any kind of higher level thinking, such as critically analysing or evaluating whatever topic is being covered. Again, I fail to see how learning outcomes (especially those that focus on these types of thinking skills) close down learning in the way Gardner Campbell suggests.

Now to the second part of my critique. As the quote above shows, Gardner Campbell cites the oft-repeated advice that ‘understand’ and ‘appreciate’ are words that have to be avoided in learning outcomes. Further on in his post though, he suggests that learning outcomes are coming from a ‘learning paradigm that avoids “understanding” and “appreciation”’. This, I think, is a misunderstanding on Gardner Campbell’s part. I would not say that the learning outcomes paradigm seeks to avoid ‘understanding’, I would say that understanding is embedded throughout it but in a way that is trying to make understanding more explicit to the learner. Understanding will be at the core of most skills or activities specified within learning outcomes, e.g. identify/assess/justify/evaluate a phenomena/topic/argument/problem etc. Of course, these different activities will most likely involve different levels of understanding, but part of a teacher’s (implicit or explicit) job is to develop students’ understanding of whatever subject or topic is being covered as their module or course progresses. What teacher would say this is not an essential part of their role? Learning outcomes, from my perspective, focus the learner on what they will be cognitively doing with that understanding, e.g. using it to identify significant factors of the First World War or to apply theories of lean management to specific engineering environments.

Of course, activities like identifying, applying, assessing etc can always be done superficially without a great deal of understanding. But if this is the case then they will also be done poorly and the student will not do well in their assessments. It is, then, in no one’s interest to ‘avoid’ understanding but it is in everyone’s interest to keep it an ingrained element of every learning experience that a student will undertake. Hence, I would argue that ‘understanding’ is actually at the heart of every learning outcome that is developed.

Finally, I have one last critique to make. Gardner Campbell’s argument does seem to imply that a learning outcomes approach will lead to more superficial learning. If he is arguing that learning outcomes reinforce a reductive behaviourist framework of learning, then he must also be arguing that learning is more superficial in this framework rather than deep and meaningful. To me, there seems to be a binary argument developing – that learning outcomes lead to behaviourist learning which closes down curiosity, complexity and fluidity in the process, and without learning outcomes we would have nothing but inquisitive learners who can take the subject/topic wherever they want it to go and satisfy only their own thirst and desire for more understanding. This latter circumstance would of course be great, but I would say that this is not the ‘reality’ that many tutors would report experiencing with their students, regardless of whether they use learning outcomes or not. Personally, and anecdotally, I hear many colleagues frustrations with the focus on summative assessments, which will often be at the forefront of students’ minds and determine, to a large extent, what they choose to focus on in their learning and how they go about learning it (see Al-Kadri et al’s 2012 paper on this topic). So, could the same behaviourist argument be applied to exams too – ‘at the end of term you will be tested on…(stimulus) so you must cram into your heads…(response)’? My point here, like I’ve made in a previous post, is that the criticisms or arguments levelled at learning outcomes can be seen to apply to many elements of the higher education process/experience. So to see learning outcomes as the sole cause, for example, of creating a turn to behaviourism is a flawed argument. And ultimately it is an unhelpful argument too because it closes down any discussion about how learning outcomes can become more meaningful learning aids for students.

Here endeth my critique!

Subscribe to Kerry Dobbins's posts

Subscribe to Kerry Dobbins's posts

Recent Comments