Student staff partnership at action in a EdEx Learning Community event

It’s a pretence. The idea that students and staff can work together in a partnership. The argument, put forward by Dr Lucy Mercer Mapstone at the RAISE Special Interest Group on Power Dynamics in Student Staff Partnerships, was convincing. I was left with the concern that ‘Student-staff partnerships’ or ‘Students as consultants’ are just names that Universities across the UK have seized upon to convince students completing the National Student Survey, that they do, in fact, belong to and are valued by their institution. But can considering power dynamics lead to more meaningful partnerships?

How can student-staff partnerships be anything but disingenuous? It would be naive, damaging and dishonest to ignore the power hierarchies that exists between a member of staff and a student. Lucy used Social Identity Theory to describe how an individual will identify with a range of groups in society. For example, I am white, female, an academic and a learning developer. I am also defined by the groups I don’t belong to – I’m not a football fan, I’m not a shopaholic, I’m not a student. Social Identity theory further suggests that the groups we belong to, we relate to and trust, but the groups we don’t belong to – the ‘outgroups’ – we are less likely to trust, see as credible, or legitimate, and less worthy of moral consideration! What does it mean then, that in the very partnerships we establish, that we begin by defining the two distinct groups? Staff or student.

We talk of ‘empowering students’, but Lucy prompts us to consider how a student and staff member relate to each other, and others within complex social, political and cultural environments. Which of the many power and privilege hierarchies are operating at any one moment? One of the most-distinct is, of course, based on their respective roles within the institution – the expert and the novice of the discipline, the grade-awarder and essay-submitter. Can there be a relationship of shared trust, reciprocity, and honesty when one can judge as ‘unsatisfactory’ the academic standard of the other, particularly when the student’s future is shadowed by graduate debt? Maybe, but it takes time and effort to establish this kind of relationship.

Can partnerships equalise this power dynamic? No – the structures are too great, too fixed within institutions and society.

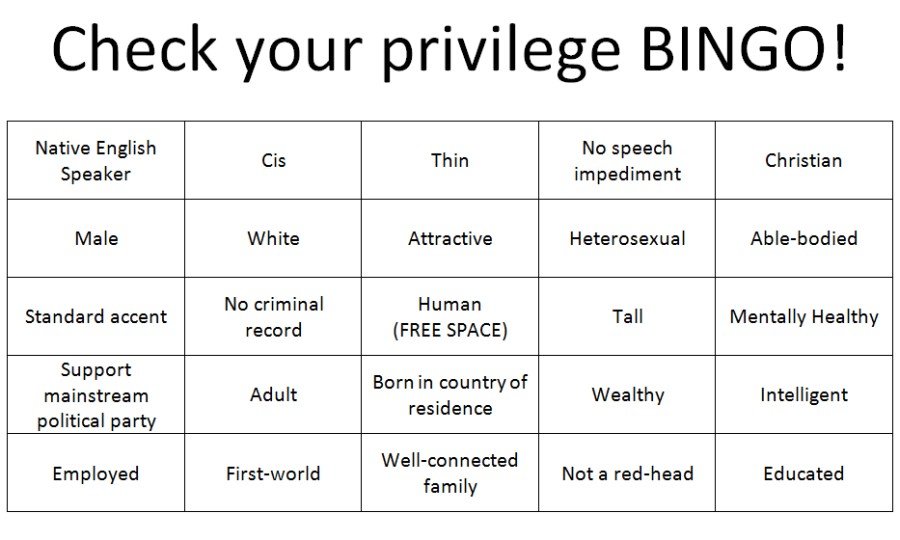

But, this is only one aspect of partnership. We must also consider the partners’ identities outside of the institution. To demonstrate this, Lucy used ‘Privilege Bingo’ to great effect within the session, despite the contestable categories, and it’s inconsistency with the Equalities Act 2010. Participants cross off which of the privileges on the ‘Bingo card’ apply to themselves (see image below) thereby highlighting what might advantage or disadvantage them in society. How privileged or not, how powerful or not is the member of staff or the student? Contrasting against the institutional roles, roles in wider-society may place more power with the student – a different dynamic exists if he is white, wealthy, upper class, able-bodied, heterosexual, and the staff member is female, black, working class-origin, and a minority in other ways. Can the likely hard-won academic achievements of this professor, be simply laid aside, to empower the student?

Privilege bingo card – how advantaged in society are you?

Ever complex and nuanced, Lucy argued that partnerships can also increase acceptance for the member of staff. The humanising aspect of working with each other may encourage, firstly the member of staff to feel confident and accepted in aspects of their identity that they may have been previously being covering. Secondly, participation in a value-driven approach may help staff in their early careers define and promote their teaching. Lastly, partnership can help individuals from minority groups to feel accepted within an institution that can feel unfriendly and exclusive, combating impostor syndrome. Hence, partnerships can help develop the partners’ identities and in doing so may disrupt power dynamics between them and others.

Lucy convinced me: We need to acknowledge and talk about power dynamics. Is power a ‘zero-sum game’ where a gain in power of the student means a loss in power for the academic? The member of staff may need to invite the student to take control, to access University resources, and even act for them when they do not have institutional agency. But can ‘giving’ students power be meaningful – after all, ‘giving’ removes choice and implies power can also be taken away.

Whilst students are not oppressed by staff, we can consider the power dynamics that Paulo Freire, educator, philosopher and writer of ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ explores in our own much less divisive context. His work suggests that we must appreciate that education is political, that teacher and student must develop and employ a critical consciousness to knowledge, roles and cultural norms within their disciplines, institutions and wider society. Fundamentally, it suggests that it takes both staff and student to reconsider and reshape the conventional expert-novice relationship, using critical dialogue.

‘While no one liberates [empowers] himself by his own efforts alone, neither is he liberated [empowered] by others’

(Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th-anniversary edition, translated by MB Ramos. New York: The Continuum., P.66)

What we can do, though, is challenge the perceived status quo. We can appreciate that power is dynamic, it changes over time, in different arenas, and it can be disrupted by a momentary action.

Why would we disrupt academic power hierarchies? Lucy argued that it may mean challenging the unspoken conventions, methods and discourse within the academic culture of the department, and considering new ways of constructing knowledge. New ways of thinking and doing may address some of the criticisms of HE around its gendered, colonial, western-centric perspectives of the world. It might mean acknowledging each person’s area of expertise, particularly the students experience of learning, and its relevance to improving higher education. Additionally and more controversially, it may be a way of critically exploring what it means to be a student in current HE. Are students actively engaged in producing themselves as human capital, developing employability skills and graduate debt for the benefit of some sections of society, but not necessarily themselves?

So, partnerships are an opportunity to explore and reflect on the complexities and dynamics of power relations, and consider different ways of thinking and working. Calling something a ‘partnership’ does not, unsurprisingly, make it so.

Lucy Mercer Mapstone at issotl18

Keynote by Dr Lucy Mercer Mapstone (Twitter: @LucyMercerMaps) at RAISE Special Interest Group event on Power Dynamics in Student Staff Partnerships at the University of Westminster.

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Dear Apatel, thought-provoking reading. I think a conversation between staff and students, (and/or either group) in multiple sessions to unpick the ideas presented here would be an extremely powerful experience for both parties. Have a look at https://cooperativelearning.works/2019/04/29/in-a-word-co-creative-conversation-explained/ for inspiration. There is a practical example from Roehampton University. Please do contact me if it piques your interest. Kind regards Jakob