Developed by Mark Van Der Enden, Tracy Dix, and Alex Patel

The challenge and rationale…

The problem with ‘study skills’ workshops are that, typically, they are boring, generic and students feel they have little relevance to them (Lea and Street, 2006; Rooney, 2016). In fact, it takes a GREAT deal of time, effort and expertise to make them interesting, contextualised for the nuances of the disciplinary culture and planned in a way that is meaningful and useful for the students to engage with them. In the majority of cases, it is better for the people marking the assignments, with support from learning developers (those who develop expertise around how people learn academic literacies), to facilitate discussions and experiential activities and give feedback on the expectations they have around effective practices in their discipline.

Whilst not a comprehensive solution to this – as our direct efforts as learning developers can only ever be generic – we have been exploring the interactive, problem solving and motivating approach of ‘Escape Rooms’, that are increasingly popular as a leisure activity and even starting to appear in Higher Education. The two sessions we ran were a success in achieving full student engagement, encouraging focused dialogue and peer learning, and ultimately, creating a fun opportunity to understand important academic practices around marking and feedback.

Here, we offer a summary of this approach, with the recommendation that it would be far more meaningful to further contextualise it – either by academics participating alongside students to share expertise, or by adapting the resources for their discipline by using real student essays, marking criteria and digital learning environments, or by asking second or third year students to create their own escape rooms for first year students – thereby developing the understanding of academic practices by both groups.

The Escape Room:

‘Thank you so much for coming! We have a crisis here in the Department of Trans-temporal Studies,’ the lecturer explains. ‘Our eminent Doctor – Emmett Brown – was recently undertaking fieldwork research back in 1885. But, tragically he is stuck there. Whilst we are not too concerned about the Doc – he’s a smart man, after all – he took with him some student essays to mark in the evenings. And we need to know what marks the students have been given before they can graduate!’

‘As I said, Doc Brown is very clever, and he managed to sneak into this building, the Fielding Johnson building, back in 1885 when it was a mental asylum. He hid a suitcase containing the student essays and his feedback to them – which we discovered this summer when this very room was refurbished. However, the passage of time has caused some of the documents to disintegrate.’

‘Your task, is to piece together the feedback, and use it to work out who the mystery essay belongs to. Only then will they be able to graduate. Good luck.’

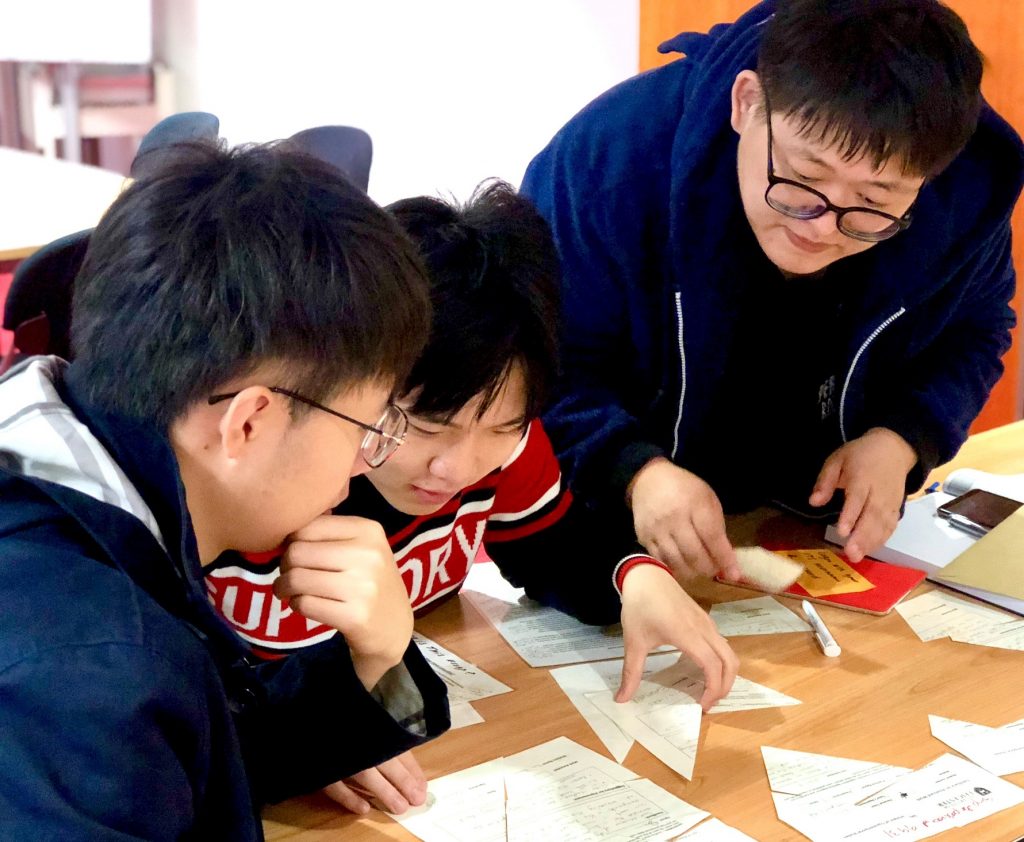

Task 1: Students must reassemble three feedback sheets which have been cut up as a jigsaw.

Task 2: Match the feedback sheets to the appropriate essay. Essays have Doc Brown’s comments written on them to help. This enables students to explore expectations around what makes a good essay – with examples. These particular essays are mock-ups written on ‘the plausibility of time travel’. On the back of one of the essays is the next clue – a hand written note from Doc Brown, asking the students to self-enrol on a module within our digital learning environment (Blackboard), and to find the marking rubric he has uploaded.

Task 3: Navigate the digital learning environment – become familiar with the typical layout of modules and quizzes (see task 4 and 5). If you work or study at the university of Leicester, then you can access this Blackboard module by self-enrolling (see slides above) on the course ‘Supporting Student Learning: Resource Hub’.

Task 4: Under the ‘Assessments’ section, students complete a Blackboard quiz where they must match the criteria with the appropriate grade classification. If correct, they then receive instructions to use this marking criteria to work out the grade classification of the essay, and to find the ‘Student Grades’ section of the Blackboard site.

Task 5: Students work out what grade the ‘mystery’ essay is, and use this and the partially obscured student number from the feedback sheet to work out which of the three students shown the essay belongs to.

Student response

The session was run with 12 and then 8 students, who had just started University. All students interacted with the activity and had meaningful discussions with each other around essays, marking criteria and feedback. Five out of the six groups successfully, with some help, matched the essays to the feedback, marking criteria and degree classification. In most cases, students were able to develop each others understanding, but in other instances it was easily apparent when students ‘got stuck’ and the facilitator was able to step in and help. The feedback was very positive with one student commenting that it was an ‘amazing experience’, and all were enthusiastic about this approach being used to address different academic pratices as well – such as note-taking, time management, writing dissertations, and collating information effectively.

As this was the first Escape Room that we have designed, it took around 5 days to create. Having learnt the process, subsequent rooms would be faster to design. This also lends itself to being developed into an online resource – although care must be taken to ensure the collaborative element is kept. This idea could be further developed by contextualising the content for a specific discipline – using actual student essays, marking criteria, feedback and Blackboard site. Furthermore, second or third year students could design an escape room for first year students as a way to develop the academic literacies of both senior students and new students.

The resources are available here, for you to use and develop yourself – please credit Leicester Learning Institute for their development.

References:

Lea, M. R. & Street, B. V. (2006) The “Academic Literacies” Model: Theory and Applications, Theory Into Practice, 45:4, 368-377, DOI: 10.1207/s15430421tip4504_11.

Rooney, S.G. (2016). Moving beyond ‘study skills’: Principles for effective practice in supporting students’ learning. Leicester Learning Institute, University of Leicester. Available here.

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Subscribe to apatel's posts

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.