Ethnographic research with craft cider-makers suggests that part of the authenticity of a craft cider derives from its staying true to the traditions of cider, as opposed to a “commercial cider”, a category often used by craft cider makers to distinguish their brew from those of lesser provenance. While I have discussed ambiguities in the way craft cider makers use the term ‘commercial’, a recent research trip to Hereford Cider Museum has shown cider in a whole new light. Rebecca Roseff, curator of the Archive of Cider Pomology based at the Museum, explained to me that cider has long been implicated in a global story of conquest and trade.

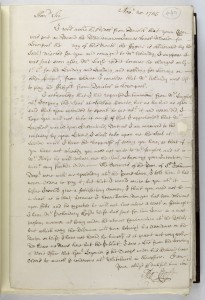

A letter (number 440) from the Bodewryd Archive. From Thomas Croft, cider merchant, to “Doctor Wynn Chancellor”, (Dr Edward Wynne of the Bodewryd Estate Anglesey, also Chancellor of the parish of Hereford) 1745. Reproduced with kind permission from the National Library of Wales (www.llgc.org.uk)

Unlike beer, which until relatively recently could not be kept much longer for a week, cider’s inherent keeping properties meant that it could also travel well. And it did. Cider accompanied travellers and troops during Britain’s colonial expansion and was the mainstay of many a domestic cellar. According to Roseff, the Elizabethan era in particular was a boom time for cider. Commonly regarded as a first era of globalisation, the sixteenth century onwards also marked a change in Britain’s landscape. Orchards became more prevalent as a response to the Tudor–era Enclosures as orcharding became a viable-and essential-side income for small-time farmers.

Due to its keeping properties, cider was therefore an important industry from its earliest days. This is evidenced by the new role of the cider merchant, someone who would not only coordinate the growers and producers, but would arrange for storage and shipping to members of the gentry, to be stored in their cellars. One such Cider merchant was Thomas Croft from Hereford, and a search of the National Library of Wales’ archives reveals that he did a roaring trade with several members of the gentry in Wales as this image of a letter, from Croft, illustrates.

This snippet of cider industry info illustrates just how extensive the cider merchants’ networks must have been. In the letter, Croft explains to his customer, Dr Edward Wynne, that he had been informed that Wynne’s “Cyder” had been taken from storage in Bristol to Liverpool at the expense of a Mr Whalley, and despatched by boat to Anglesey by a Mr Last:

“I suppose it was sent soon after Mr Last received it because he charged only 1s 6d for the landing and Haulling and nothing for Storing or other payment from whence I conclude that Mr Whalley was left to pay the freight from Bristol to Liverpool”.

Croft’s role appears to be that of an overseer of the distribution, rather than a merchant in a face to face sense, something that in all probability was only possible with a commodity, like cider, that could keep for long periods of time, and therefore lent itself well to Croft’s rather remote mercantilism.

Historically then, cider must be seen as a commodity, and I suggest that this history differs greatly from the perception of cider, and craft cider in particular, as a down-on-the-farm, “traditional” drink. If we can say that modern craft cider is “traditional”, then can we also say that cider, as a portable commodity implicated in the process of globalisatioon, is traditionally “modern”?

Subscribe to 's posts

Subscribe to 's posts

Recent Comments