In the story of pulque, we have so far thought about different origin stories about pulque and their role in political and cultural processes in Aztec Mexico. Being linked to the origin or discovery of pulque carried a certain prestige value, but why?

In many ways, pulque was not singled out, but was one of several material substances that played a special role in Aztec culture and ritual. Corn, or maize, is the most obvious example of a material foodstuff that was revered as the staff of life, was embedded in religious and philosophical thought, and featured ubiquitously in ceremonial and ritual practices. Particular foods and drinks like this were so important because they were means through which humankind, the natural world and divine or godly forces could communicate, connect and overlap with one another. Foods and drinks with deep connections to everyday material life and with a deep history in the region seem to have acted in this way in indigenous cultures. Maize – the cornerstone of Mexican cuisine for centuries – was one. Pulque – being derived from the maguey or agave plant that provided everything from building materials, paper and fabrics to food and drink – was another.

Pulque’s special status as a material substance connecting together human, natural and divine worlds was also due to its intoxicating properties. Intoxication was understood as a state of instability and unpredictability that was also valuable as means of transferring between human, divine and natural states of being. Pulque – together with chocolate, tobacco, blood and hallucinogenic substances – fulfilled this special function, which was at the heart of much of the Aztecs’ religious and ritual life [1]

Stone carvings of “drunkards” from Aztec period, showing different emotional states produced by pulque. Photo by Deborah Toner, Museo Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico City

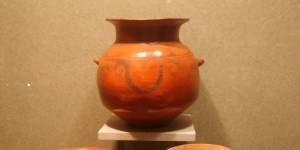

Pulque was associated with many Aztec deities, including Mayahuel (goddess of fertility and essential a divine version of the maguey plant), Tlaloc (god of rain), Ometochtli (two-rabbit, god of pulque) and others. The rabbit was also linked to the moon in Aztec culture, and the cycles of life, fertility and death represented by the moon, and so vessels made for drinking pulque during ceremonies often have rabbit symbolism and/or a crescent, half-moon shape symbol called the yacametztli.

Pulque vessels with rabbit symbolism. Photo by Deborah Toner, Museo Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico City

Pulque was used in agricultural ceremonies to encourage the health and well-being of crops and in festivals celebrating the harvest, both by being drunk by the celebrants of these ceremonies and by being offered as a gift or sacrifice to the gods responsible for fertility and growth. Pulque was also consumed by the priests and warriors who conducted ceremonies, to better facilitate their communication with divine forces and indeed to enable them to become divine. For similar reasons, pulque was given to those destined to become human sacrifices.[2]

The Aztec leadership also imposed strict protocols about who could consume pulque, when, in what quantities and for what purpose. With a few exceptions, pulque was officially restricted to military, religious and political elites, and commoners found drinking pulque in unsanctioned contexts could be severely punished. Pregnant women, lactating women and the elderly were also allowed to drink pulque, for its associations with fertility, purification and renewal, but the quantities they could legally consume were restricted and consumption was often limited to a particular ritual context. There is considerable debate about the extent to which these rules were enforced in practice, especially considering that aguamiel – the sap from which pulque ferments naturally – was much more freely available. This situations seems a bit like the cartons of grape juice on sale in Prohibition-era America with the instructions: “After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in the jug away in the cupboard for 20 days, because then it would turn into wine.”[3] Hmm.

But the fact that the rules existed, even if they couldn’t be enforced widely, show that pulque had a high symbolic and cultural value: if pulque opened up an unstable channel through which human, divine and natural worlds could interact, it was important to try to control that force and limit it to those deemed powerful and prestigious enough to use it. This also indicates why the stories of pulque’s origin discussed in the previous post had such political and cultural meaning: embedding themselves in the story of pulque’s origins, was one way that the Aztec ruling elite could claim originary status in the foundation and development of the key principles of political and cultural life in Central Mexico, over which they were establishing dominion. Of course, claiming connections to pulque’s origins was only one of many ways they did this, but clearly an important one.

1. Marcy Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (Cornell University Press, 2008), 20-43.

2 . Oswalso Goncalvez de Lima, El maguey y el pulque en las codices mexicanos (Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1956).

3. Paul Aaron and David Musto, ‘Temperance and Prohibition in America: A Historical Overview,’ in Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition, ed. Mark H. Moore and Dean R. Gerstein (National Research Council, 1981), 159

Subscribe to Deborah Toner's posts

Subscribe to Deborah Toner's posts

Good post, i definitely appreciate this site, keep on it