How can a book be so current and so dated at the same time? This was at the forefront of our minds as we met to discuss Waugh’s 1938 parody of Fleet Street and the world of foreign correspondents. The book is drawn from Waugh’s own experiences as a journalist in Abyssinia, but far more lighthearted. Waugh was in fact something of a pariah amongst his fellow journos, and enjoyed none of the (wholly accidental) success of his affable protagonist William Boot. Scoop begins with a case of mistaken identity as Boot, who writes a gentle column on country life for the Daily Beast, is suddenly uprooted and sent to cover a civil war in the fictional African nation of Ishmaelia. Lord Copper, the Beast’s proprietor, had intended to employ William’s cousin- the ambitious novelist John Boot – but his foreign editor sends the wrong man. Hilarity ensues.

Now seasoned Waugh readers, we rather feared for William. Nice folk do not always do well in Waugh’s comedies, and William Boot is one of the nicest characters we have met. He is entirely unworldly, as Waugh reveals in the polite telegrams Boot sends back to the Beast:

NO NEWS AT PRESENT THANKS WARNING ABOUT CABLING PRICES BUT IVE PLENTY MONEY LEFT AND ANYWAY WHEN I OFFERED TO PAY WIRELESS MAN SAID IT WAS ALL RIGHT PAID OTHER END RAINING HARD HOPE ALL WELL ENGLAND WILL CABLE AGAIN IF ANY NEWS.

Boot signally fails to grasp that, if there is no news to be had, he must invent it – and his ingenue conversations with fellow journalists reveal the character of his unchosen profession:

“But if we all send the same thing it seems a waste.”

“There would soon be a row if we did.”

“But isn’t it very confusing if we all send different news.”

“It gives them a choice. They all have different policies so of course they have to give different news.”

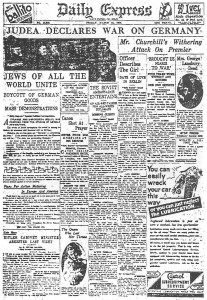

This advice led to a lengthy discussion of our own news platforms. Despite huge changes in media delivery since 1938, we all agreed that the way news is presented and manipulated has stayed pretty much the same. A handful of powerful news channels can create a story simply by paying attention to it – or “kill” it by focussing on something else. It is Ishmaelia’s misfortune that Lord Copper and his fellow tycoons have pinpointed it as a ‘very promising little war.’

So, this is book that remains as relevant today as it did before WWII. Well, yes – and no. Many of us felt pretty uncomfortable reading the Ishmaelia sections for,

even as we laughed, we winced. There is no denying that the language used to describe Ishmaelians marks this very much as a book of its time. We couldn’t even excuse Waugh (if we wanted to) by saying that it’s the characters who use racist terms and not the narrator – because, in the middle of a passage about a taxi journey, the narrative voice uses a term so offensive that the youngest member of our group had never even heard it before. What do we do with language like this? Context can be enlightening. It was, for example, perfectly normal for the mainstream press to drop the n-bomb in the thirties. Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926) uses it liberally, and not in the mouths of unsympathetic characters. By contrast, searching through about 7,500 of Waugh’s letters and diary extracts finds about 15 instances of the word. And it is worth remembering that everyone is grotesquely charicatured in Waugh. This is a problem for anyone reading outside contemporary literature, and we didn’t come up with any solid answers beyond agreeing that censorhip is unhelpful and masks the issues at stake.

On a more conceptual level, Scoop plays beautifully with what “foreign” means. Once William Boot is safely back in the countryside, he is visited by the Beast‘s foreign editor Mr Salter. Salter is a creature of the town, with its ‘cosy horizon of slates and chimneys’, and is totally bewildered by the countryside. A different language is spoken here, he gets hopelessly lost and arrives at the family seat of Boot Magna so dishevelled and disorientated that Boot’s elderly relatives believe he is drunk. Rural England is a more frightening experience for Salter than the Ishmaelian war had proved for Boot. But this gentle humour has a serious point. In Scoop, Waugh shows us a developing country totally at the mercy of Western media, political and business interests. Agents in this game think nothing of engineering a war to suit their own ends. This sting in the tail of Waugh’s most upbeat comic novel is captured in the soft menace of his closing lines:

Before getting into bed he drew the curtain and threw open the window. Moonlight streamed into the room.

Outside the owls hunted maternal rodents and their furry brood.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

You are absolutely right about Scoop being so current and yet so dated!

I think all the stuff about putting spin on things that we talked about was very interesting – what “makes” a news story and what doesn’t. Poor William didn’t seem to have a clue but he ended up with the Scoop anyway! I suppose this is quite comforting really, in comparison to a lot of other calamitous Waugh protagonists.

Something I forgot to mention on the day but have just remembered now is how reminded I was of The Railway Children when we were looking at the scene with Mr Salter talking to Bert Tyler about getting to Boot Magna. In the Railway Children the mother and her children are taken by a chap with a very broad accent (“I dare say” !) to their new house in the country. Coming from London they are completely unaware and unaccustomed to the countryside and I just thought that this dynamic was slightly comparable.