The following is a guest post kindly supplied by Ben Doty.

The upcoming conference Evelyn Waugh and His Circle has most of the regular staff at the blog tied up, so I offered to step in and report on April’s meeting of the book group.

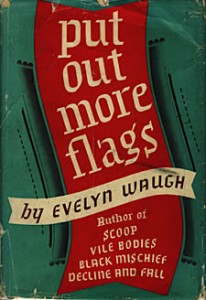

Put Out More Flags is a hidden gem among Waugh’s works, the group decided. It features Basil Seal (clearly a favourite character of Waugh’s, judging from his frequent reappearances, from Black Mischief to ‘Basil Seal Rides Again’) and a host of other returning Waugh characters during the Phoney War at the outset of World War II.

In this time of national enterprise, when everyone is in it together, being asked to sacrifice for their country, most of the characters just seem to want to be left alone. Angela Lyne, a socialite and sophisticate, cloisters herself in her London flat, listening to the lights going out all over Europe on the radio. Barbara Sothill, Basil’s sister, cringes at the arrival of her husband and his entire regiment, who will be camping on the lawn at her country home. And although Waugh focuses on the plight of the upper classes, it is also made clear that urban evacuees who are being billeted out in the countryside under the direction of Barbara and others like her are no more pleased about being forced into close quarters with others. The buried irony in this scene is that while no one wants to be in this situation, the entity forcing them into it is the government, which, in theory, is an embodiment of their collective will.

Some of these city people, a trio of unruly children named the Connollies, supply many of the novel’s best moments. They are so badly behaved that Basil quickly realizes people will pay him to take the Connollies off their hands. He sets off, lodging them in each moderately well-to-do home in the countryside until the owners return, begging Basil find another home for the Connollies. The first time this happens, Basil tries appealing to the billetter’s sense of humanity:

‘“You surely wouldn’t suggest sending them back to Birmingham to be bombed?”

This was an argument which Barbara often employed with good effect. As soon as Basil spoke he realized it was a false step. Suffering had purged Mr. Harkness of all hypocrisy. For the first time something like a smile twisted his lips.

“There is nothing would delight me more,” he said.’

For all the misfortune Basil put them through, the Harknesses did not emerge as the sympathetic ones in this exchange. It becomes apparent that the Connollies, who initially seemed feral and disturbing, begin to display a calculating intelligence that is fun to watch—they become Basil’s partners. The Harknesses, on the other hand, are infuriatingly precious. Mr. Harkness buys a home in the countryside, the ‘Old Mill House’, as a home to retire to. His working life was ‘haunted by only one fear; that he would return to find the place “developed”’. It is not, and he and his wife are able to retire to a fetishised version of the countryside: one with all the pleasing aesthetic elements but none of the meaning behind those elements. Their home is an old mill—literally a building with a functional purpose that they have ended. The draining of its pond is the starkest representation of this.

The book group was intrigued by Basil’s seemingly pure amorality. He drifts through wartime Britain emulating his heroes, ‘the hard-faced men who did well out of the war’ in 1918, with no thought at all to the morality of his actions. By the end, however, he has committed to marry Angela (formerly his mistress) and enlisted in the war. This pairing was ultimately a bit puzzling—why would Basil seek marriage? Angela was wealthy, but the group felt there was more character development involved. Angela’s choice, too, was a bit puzzling. She had been one of the many well-developed and interesting female characters in the novel, one who desired her privacy and was perfectly self-sufficient. The onset of war sent her into an alcoholic spiral, though, and it took Basil to pull her out of it—he moderated her drinking in a way only Basil could have come up with. He drank with her:

‘in general the new arrangement worked well. Angela drank a good deal less and Basil a good deal more than they had done for the last few weeks and both were happier as a result.’

Basil, a figure of comic fun in Black Mischief, achieved greater depth in Put Out More Flags. Women in the novel were also much more well-rounded than some of his other works—Angela, Barbara, Molly and others are strong and interesting. Even evacuees and billeters reveal hidden depths. On the strength of its characterization alone, this, the book group found this to be one of Waugh’s strongest novels, and was surprised it is not better known.

The book group will meet next on May 16th, at 11 AM, to discuss Nancy Mitford’s novel Pigeon Pie. Mitford was a confidante of Waugh’s, and Pigeon Pie is set around the same time as Put Out More Flags.

Subscribe to Rebecca Moore's posts

Subscribe to Rebecca Moore's posts

[…] repay, is relieved to escape to Azania to assist his college friend. We will meet him again in Put Out More Flags and the short story Basil Seal Rides Again. Seth establishes a Ministry of Modernisation with the […]