The first thing we noticed about the second book in Waugh’s trilogy was the ambivalence of its title. Playing on the traditional description of a man as ‘an officer and a gentleman’, the plural form ‘officers and gentlemen’ instead implies that a man can be rather one or the other: and there are very few gentlemen left at all in this case.

The first thing we noticed about the second book in Waugh’s trilogy was the ambivalence of its title. Playing on the traditional description of a man as ‘an officer and a gentleman’, the plural form ‘officers and gentlemen’ instead implies that a man can be rather one or the other: and there are very few gentlemen left at all in this case.

Officers and Gentlemen is darkly cynical, offering up a cast of wartime soldiers who rise through the ranks by cunning or accident, but never by merit. And the war itself, as we saw in Men at Arms, flails on with no sense of planning or strategy into deadly farce.

This farce is performed in two acts. First, there is the black comedy of the Isle of Mugg, which features characters in sympathy with Waugh’s earlier satires such as the laird’s fascist, cheerfully unhinged great-niece Katie who compromises Crouchback by leaving incendiary leaflets in his car. Elizabeth-Anne wondered if Katie might be inspired by Unity Mitford, younger sister of Waugh’s friend Nancy, who expressed a fiery passion for Hitler. Trimmer, too, the most ungentlemanly of the new breed of officers, makes his appearance on Mugg as the ostentatiously Scottish “McTavish” before ending up in a raid on occupied France. During the raid McTavish/Trimmer trips over an unmapped railway in the dark and decides he might as well blow it up. This act ultimately results in his celebration as a war hero.

Act two is the tragedy. The first “real” action Guy sees is the evacuation of Crete, and there is nothing funny about this farce. The island is presented as a disorientating hell, upon which more than one officer loses his soul. What struck us most about the episode was Waugh’s focus on the changing meaning of the word “liberation”:

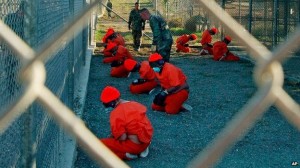

‘Italian prisoners,’ he explained. ‘Not a happy party…They’ve got a very fierce doctor in charge who says it’s contrary to international convention to turn unwounded prisoners loose until the end of hostilities…’

In a year or two of war ‘Liberation’ would aquire a nasty meaning. This was Guy’s first meeting with its modern use.

This description of the abandoned prisoners of war, some of whom are murdered byGerman strafing a few lines later, finds deep resonance in our post-9/11 world. This is especially true in a week when the extent of the CIA’s involvement in torture during the “War on Terror” has been made clearer. Crouchback’s “liberation” is our “democracy”, our “extraordinary rendition”, our “rectal hydration”.

Crouchback is rescued from Crete by Corporal-Major Ludovic, in the murkiest of circumstances. Everyone else in their boat dies, and the implication – which, Rebecca tells us, is more explicit in the William Boyd film adaptation of the trilogy – is that Ludovic murders them and spares the delirious Crouchback o provide him with an alibi. The experience renders Guy voluntarily mute, and the passages devoted to his “recovery” in hospital are amongst Waugh’s most lyrical:

Silence was all. Ripeness was all. Silence swelled lusciously like a ripening fig, while through the hospital the softly petulant north-west wind, which long ago delayed Helen and Menelaus on that strand, stirred and fluttered.

This silence was Guy’s private posession, all his own work.

We discussed many theories for Guy’s silence. Ben suggested that it was the only way he could avoid following orders and being dragged back into a war which no longer held any moral worth for him. But he is dragged back, by Waugh’s recurring character Mrs Stitch. In her way as unsettling a force as Ludovic, Mrs Stitch coaxes Guy back to existence and covers up the ignoble actions of his fellow officers on Crete. In the narrative equivalent of a sucker-punch, she throws away an envelope passed into her care by Guy. She, we assume, thinks it contains incriminating information. It actually contains the identity tags of a young, dying soldier Crouchback encountered on Crete.

There is little joy for the protagonists of our sub-plots, either. Guy’s ex-wife Virginia has a brief affair with Trimmer , but by the end of the novel seeks to be rid of him. Instead, she is pushed into accompanying him on a propaganda-tour of America. I thought this amounted to her being pimped out by the British Army; other members of the group were less sympathetic, and saw the predicament as her just desserts. Only Guy’s father, the beatific Gervase Crouchback, carries on his existence in ignorance of the malice of those around him. His serenity and unswerving faith in the goodness of people is the one beacon of hope – like the relit chapel lamp in Brideshead Revisited – in a bleak world.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

[…] something of the other-worldliness of trauma that recalls the nightmare landscape of Crete in Officers and Gentlemen. The sinister Major Ludovic falls apart completely when confronted once again with Guy, finding […]