In this second post of our series exploring the collection holders that we have worked with at the Midlands UOSH hub, Elizabeth Gray looks at the UK Sword Dance Archive.

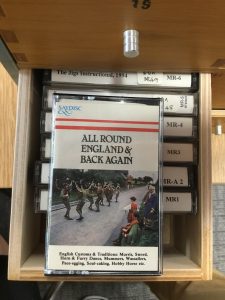

In contrast to Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service which we explored in our last post, today’s archive is much more specialised. The UK Sword Dance Archive consists of one collection focused on preserving the art of sword dancing, as well as other traditional folk and Morris music and dance practices in Britain. The collection contains a wealth of material including recordings of live performances, radio programmes, lectures, and commercial music. Additionally, oral history interviews with significant individuals within the folk music and dance community from the 1950s to 2000s have been collected. As the Sword Dance Archive has systematically gathered all these sources together, it offers a unique learning resource for both established performers and new comers to the art form.

The archive was collected by Ivor Allsop, a key figure in the folk dancing community with a particular interest in the Yorkshire longsword folk-dance tradition. Between 1978 and 1980 Allsop held the post of ‘Squire of the Morris Ring’, and helped to develop better preservation and cataloguing practices for the Ring’s archival material. The collection is now held by Phil Heaton, who himself is a practitioner of the rapper style of sword dancing.

Some of the highlights of the collection are the recordings of lectures held at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. These give an insight into the history of sword and folk dancing and include topics such as the first International Folk Dance Festival held in London in 1935. These are complemented by the oral history interviews with notable figures such as Tony Foxworthy, founder of Whitby Folk Festival; Roy Judge, former president of The Folklore Society; and Marjorie Fennessy, leader of the Whirligigs dance group. Another highlight is the recording of the funeral of Lionel Bacon, Squire of the Morris Ring, 1962-1964, which shows another side of the sword and folk dance community.

As folk dance is a form of intangible culture, written sources on their own cannot give a complete picture of its traditions and practices. Thus, collections such as The UK Sword Dance Archive are instrumental in providing a more thorough representation of the practice, enhancing the community’s ability to share and pass down its traditions. Prior to the UOSH project the recordings in this collection were under threat due to issues such as format obsolescence. Thanks to the work of the Midlands Hub, however, The UK Sword Dance Archive will continue to be preserved, allowing the traditions of sword and folk dance to live on.

Further Reading:

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2012/nov/22/ivor-allsop-obituary

https://www.sworddanceunion.org.uk/

Phil Heaton has kindly added these notes:

Although Sword Dancing is a pan-European activity with many references to presentations from the C.14 up to modern times, the English dances have proven to have both tenacity and longevity. The two types of English sword dance, Longsword and Rapper have developed into highly complicated performances with skilled displays in many different arenas in the UK, the United States and across Europe where English sword dancing has become popular.

There are suggestions that whereas the Morris dance of middle and southern England is a continental import related to the Moors who made massive inroads into the Iberian Peninsular, their dances being adopted by the European Courts; the Sword Dance is mainly found in the old Danelaw, in the counties of North Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and especially in Durham and Northumberland. Although there are no records of sword dances in the Scandinavian countries and certainly no records of the dances left by the Norse invaders so it seems that the sword dancers could have been peculiarly English activity.

Longsword as the name suggests is danced with longish wooden or more usually steel swords. It was mainly performed by groups of agricultural workers who performed seasonally when there was little outdoor work available. Longsword became a highly developed activity in the Industrial areas of Sheffield where the Industrial Revolution drew in skilled and determined artisans. The two dances of Sheffield, Grenoside in the North and Handsworth to the South of the city are excellent and complicated developments obviously built on simpler styles.

Rapper is the name given to the dances of Co. Durham and Northumberland where the simpler styles were adopted by the many imported colliers brought in to work the thousands of coal pits and collieries that wealthy landowners had sunk to get at the coal just under the surface. These incomers met with the Geordie locals and brought with them clog and step dancing and a need to earn money when the pits were closed from November to March. The owners shut the pits down as the seas became too wild to export coal to London where it was sold. The pitmen, without any earnings, gathered in small usually family units and developed the sword dances with short industrial spring steel tools as dancing implements. Music Hall attention – grabbing styles, bright music, and smaller performing areas defined the Rapper and it became a slick, fast and entertaining performance that could earn money on the streets and in the pubs and entertainment venues in the cities and towns. Having a thriving and musical input of Irish, Scottish and Welsh workers helped.