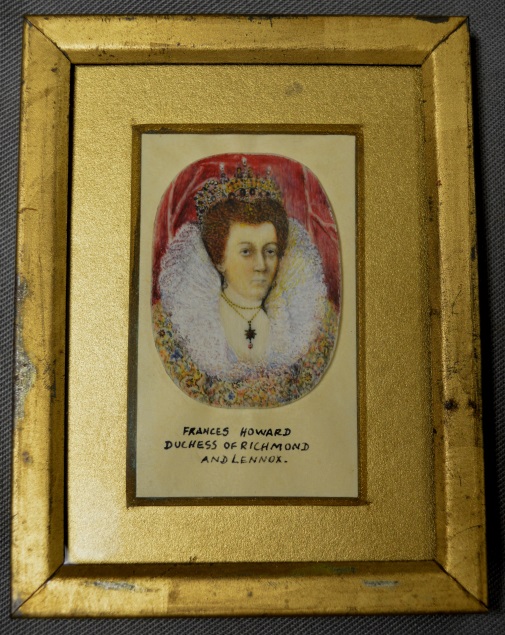

Amongst the contents of the Fairclough Collection of engraved portraits, relating to political and social history in 17th century Britain, we have recently discovered this delicately executed miniature of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, who died in 1639. The oval appears to have been cut from a larger composition (in watercolour or gouache?), and is displayed in a gold mount and frame and inscribed with the name of the sitter in Basil Fairclough’s hand.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Miniature of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, from the Fairclough Collection

Frances Stuart was one of the most celebrated beauties of her day and the target of much scurrilous gossip. Although she came from noble stock (her two grandfathers were the Dukes of Norfolk and Buckingham), she was orphaned at the age of 3 and, as she approached marriageable age, found herself without a dowry. In 1591, aged only 13, she was married to Henry Prannell, described rather contemptuously by Wilson as ‘a Vintner’s Son’1, although, in fact, Prannell’s father was an Alderman of London, an honour reserved for ‘the most respectable of the commercial order’2. Prannell nonetheless felt obliged to write to William Cecil, Lord Burghley (who had intended to arrange a match for Frances) apologising for marrying her:

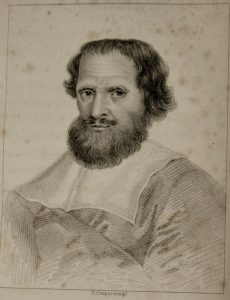

University of Leicester Special Collections. Engraved portrait of astrologer and medical practitioner, Dr Simon Forman from: SCM 10949, William Lilly, William Lilly’s History of His Life and Times, from the Year 1602 to 1681, (London, 1822).

‘The gentlewoman I have a longe time loved dearlie, being bounde thereunto by her mutuall liking of me; little or nothing I expected with her, considering she had litle or nothing to mainetaine and preferr her self, she being destitute of friendes and abilitie I thought it a most frindlie parte … to present her my selfe and therbie to make her partaker of all wherewith God hath blessed me …’3

The couple had no children and, while Prannell was away at sea, from May 1597 onwards, Frances began to visit a London astrologer and medical practitioner, Dr Simon Forman. She reportedly wanted to know whether Henry would return and, if he did not, whether she should marry Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, her ‘love’. And also to learn ‘by giving water (in July and August) whether she were pregnant’4. Henry did return, but in December 1599 he died, leaving his entire estate to Frances, who was still only 21.

When she came out of mourning, not surprisingly, the wealthy widow had many suitors, one of whom, Sir George Rodney, was pushed over the edge by her rejection. As John Chamberlain observed, in a letter to Dudley Carleton on 3 February 1601, ‘[Rodney’s] braines wer not able to beare the burthen, but have plaide banckrout and left him raving’5. He travelled to Amesbury, where she lived, and, at an inn in the town, wrote her a lengthy ‘Elegia’ in his own blood. Lodge reproduces this, along with Frances’ reply, also in rhyme:

‘No, no I never yett could hear or prove

That there was ever any died for love’6.

On receiving this, Rodney ‘cut his owne throat as an earnest of his love’7 – but not before he had penned a final short verse!

‘Ah mee! Myselfe, myselfe must kill,

And yett I die against my will’8.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Engraved portrait of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, from the Fairclough Collection, (undated), EP42B/Box 3/R.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Engraved portrait of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, from the Fairclough Collection, (undated), EP42B/Box 3/R.

Instead of Rodney, on the advice of Dr Forman, Frances selected from amongst her suitors, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, who was 61 at the time and a widower twice over. Seymour offered her a jointure of between four and five thousand pounds a year, if he should die. But the marriage does not seem to have been a happy one and Frances was forced to live in the country, rather than at court, where she very much desired to be. Wilson takes delight in relating how, ‘when she … found admirers about her, she would often discourse of her two grandfathers, the dukes of Norfolk and Buckingham … but if the earl her husband came in presence, she would quickly desist; for when he found her in these exaltations, to take her down he would say, Frank, Frank, how long is it since thou wert married to Prannel?9’ Seymour’s use of the pet name ‘Frank’ perhaps suggests that this was affectionate teasing, rather than simply a spiteful attempt to draw attention to her former union with ‘a mere Vintner’. Whatever the case, he defied expectations by surviving to the age of nearly 82 and, if Wilson is to be believed, while he still lived, Frances allowed herself to be courted by Ludovick Stuart, Duke of Lennox (and later also of Richmond), who ‘presented many a fair offring to her, as an humble Suppliant; sometimes in a blew Coat with a Basket-hilt Sword, making his addresses in such odd disguises’10.

Only a few weeks after Seymour’s death, Frances was secretly married to Stuart and the couple proceeded to live extravagantly, as befitted their wealth and rank. ‘The new Duches of Lennox takes state upon her (they say) after the old manner, which is out of date long ago’11, Chamberlain reports with relish. But Chamberlain, it must be said was a shocking purveyor of gossip, who would have loved social media and whose letters are peppered with ‘as some say’, ‘the world says’ and so on. He certainly did not approve of Frances, whom he referred to as ‘the double Duchesse, or (as some wags call her) the Duchesse cut upon Duchesse’12 and ‘this Diana of the Ephesians’13 (an allusion to the great goddess, ‘whom all Asia and the world worshippeth’ – Acts 19: 27).

University of Leicester Special Collections. Engraved portrait of Ludovick Stuart, Duke of Richmond and Lennox, by R. Clamp after Paul van Somer, (London, 1795) from: SCM 10792, Francis Godolphin Waldron, The Biographical Mirrour …, (London, 1795).

‘[The Duke of Richmond] died of an apoplexie in his bed on Monday morning,’ Chamberlain writes on 21 February 1624. ‘His Lady takes yt extreme passionately, cut of her haire that day with divers other demonstrations of extraordinarie griefe, as she had goode cause as well in respect of the losse of such a Lord, as for that she foresees the end of her raigne’14. And again on 10 April, ‘The Duke of Richmonds funeral is to be at Westminster the 19th of this moneth. There hath ben a herse, with his statue on a bed of state above these sixe weekes at Hatton House, where there hath ben great concourse of all sorts, and all things are and like to be performed with more solemnitie and ado then needed: but that yt so pleaseth her Grace to honor the memorie of so deare a husband, whose losse she takes so impatiently and with so much shew of passion that many odd and ydle tales are daylie reported or invented of her, insomuch that many malicious people impute yt as much to the losse of the court as of her Lord, and will not be perswaded that having buried two husbands alredy and being so far past the flower and prime of her youth she could otherwise be so passionate’15.

Frances survived her third husband by 15 years and did not remarry. According to Wilson, ‘she vowed after so great a Prince as Richmond, never to be blown with the Kisses, nor eat at the Table of a Subject, and this Vow must be spread abroad, that the King may take notice of the Bravery of her spirit’16. But, if she did indeed set her sights on the old King James, he did not take the bait. She continued to enjoy her wealth and live in great state – Chamberlain disapprovingly describes the ‘magnificence’ of her progress to chapel in January 1625, ‘her fowre principall officers steward, chamberlain, treasurer, controller, marching before her in velvet gowns with their white staves, three gentlemen ushers, two Ladies that bare up her traine, the Countess of Bedford and Mongomerie following with the other Ladies two and two’17. She died at the age of 61 at Exeter House in the Strand and is buried beside Ludovick Stuart in Westminster Abbey. Lodge quotes a letter in the Strafford papers, which shows that, even in her dying moments, she was ‘surrounded by the officers of her household, bearing white wands, and other ensigns of their respective stations’18.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Engraved portrait of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, engraved by P. Lightfoot (London, 1836) from: SCM 10788, Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain …, (London, 1840), Vol. 4, No. 20.

Special Collections welcomes students, researchers, staff and visitors who wish to consult the University of Leicester’s collection of rare books, archives and manuscripts. To arrange a visit to view any particular items from the Fairclough Collection, please email us at specialcollections@le.ac.uk for more information. Please do contact us, if you have any comments about the miniature or are able to make a judgement as to its age.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Miniature of Frances Stuart (née Howard), Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, from the Fairclough Collection

- Arthur Wilson, The History of Great Britain: Being the Life and Reign of King James the First …, (London, 1653), p. 258, SCT 01171

- Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain …, (London, 1840), Vol. 4, No. 20, p. 1, SCM 10788

- Henry Ellis, Original Letters, Illustrative of English History …, Third Series, Vol. 4, (London, 1846), p. 91, SCM 13319

- Donald W. Foster, ‘Stuart , Frances, Duchess of Lennox and Richmond (1578–1639)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, 2004) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/70952

- John Chamberlain, The Letters of John Chamberlain, Vol. 1, (Philadelphi, 1939), p. 116, FAIRCLOUGH DL.CHA

- Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain …, (London, 1840), Vol. 4, No. 20, p. 9, SCM 10788

- John Chamberlain, The Letters of John Chamberlain, Vol. 1, (Philadelphi, 1939), p. 126, FAIRCLOUGH DL.CHA

- Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain …, (London, 1840), Vol. 4, No. 20, p. 10, SCM 10788

- Arthur Wilson, The History of Great Britain: Being the Life and Reign of King James the First …, (London, 1653), p. 259, SCT 01171

- Ibid., p. 258

- John Chamberlain, The Letters of John Chamberlain, Vol. 2, (Philadelphia, 1939), p. 408, FAIRCLOUGH DL.CHA

- Ibid., p. 499

- Ibid., p. 594

- Ibid., pp. 545-6

- Ibid., pp. 551-2

- Arthur Wilson, The History of Great Britain: Being the Life and Reign of King James the First …, (London, 1653), p. 259, SCT 01171

- John Chamberlain, The Letters of John Chamberlain, Vol. 2, (Philadelphi, 1939), p. 595, FAIRCLOUGH DL.CHA

- Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain …, (London, 1840), Vol. 4, No. 20, p. 12, SCM 10788

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments