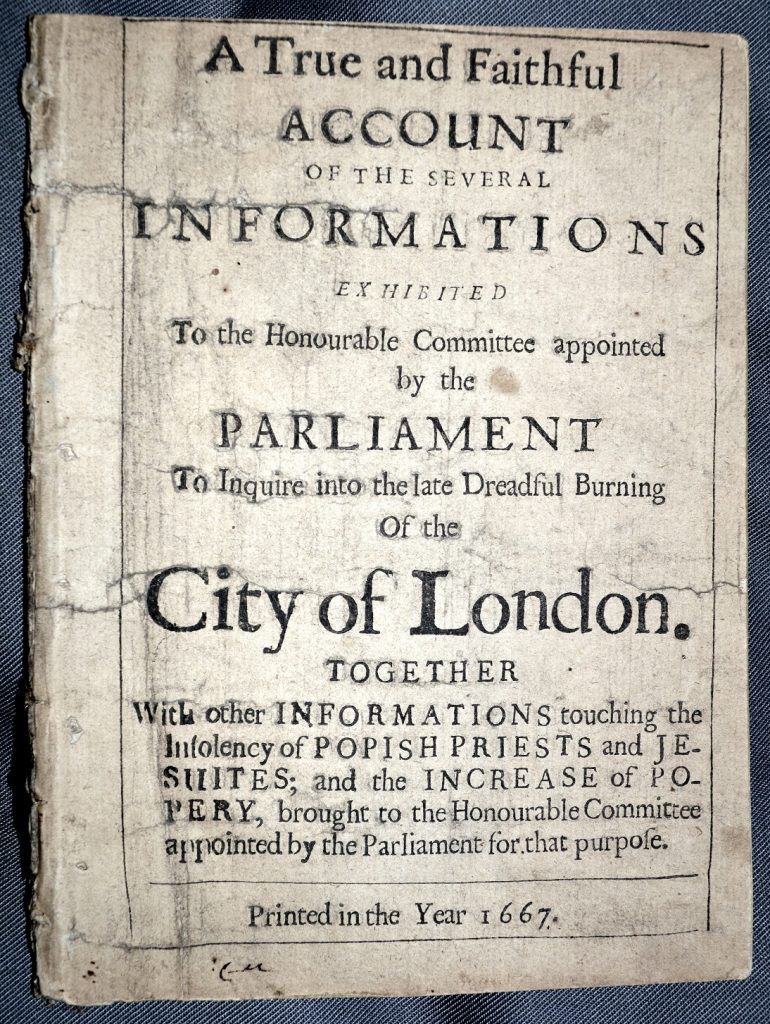

The atmosphere of London in 1666, before, as well as after, the outbreak of the Great Fire, was febrile – anti-Catholic feeling was potent and rife, portents and prophecies of terrible events abounded, the city had been ravaged by Plague the year before and England was at war with the Dutch, with whom the French had allied in January. Here I discuss one of the many eye-witness accounts accusing Catholics of fire-raising, which was related to ‘The Honourable Committee appointed by the Parliament to inquire into the late Dreadful Burning of the City of London’ and subsequently published in a pamphlet of 1667. This is one of a large collection of pamphlets belonging to the Special Collections.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Front cover of the pamphlet, A True and Faithful Account of the Several Informations Exhibited to the Honourable Committee Appointed by the Parliament to Inquire into the Late Dreadful Burning of the City of London, (London, 1667), SCM 05525.

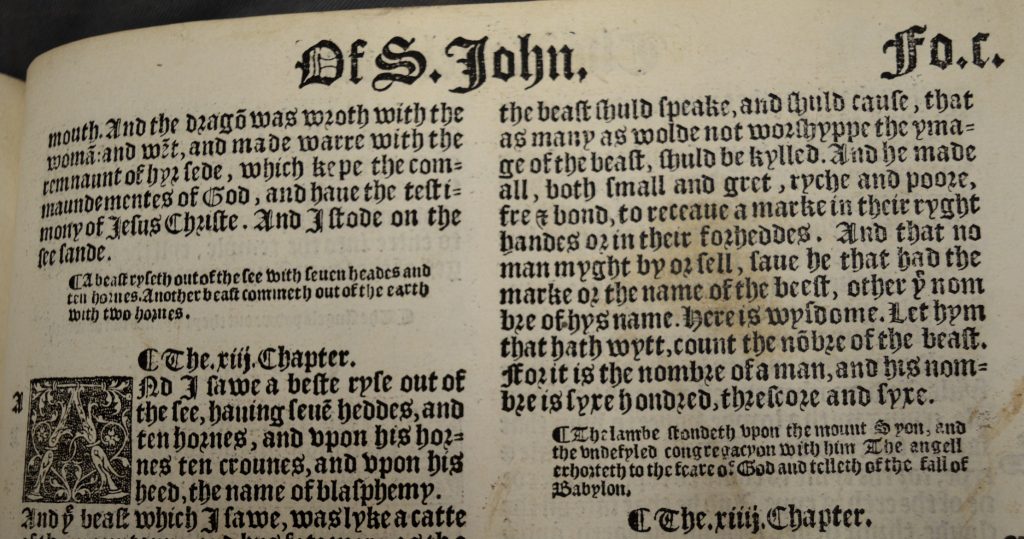

Since the reign of Elizabeth I, a powerful anti-Catholic sentiment had grown up, fed by such incidents as the burning alive of hundreds of Protestants during the reign of Mary and the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Catholics were widely believed to be merciless and ruthless and to intend to wipe out Protestantism. They, the Jesuits in particular, were also believed to be expert in the use of ‘fireballs’. In addition, there had been a flood of doom-laden prophecies about the year 1666, sparked by the occurrence in it of three sixes, an ‘Apocalyptical and mysterious number’1, as the astrologer John Booker noted. This superstition stemmed from the much-debated and mysterious verse, Revelation 13:18: ‘Here is wisdom. Let him who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for the number is that of a man; and his number is 666’. As far back as 1648, William Lilly had predicted that the year would be ‘ominous to London, unto her merchants at sea, to her traffique on land, to her poor, to all sorts of people … by reason of sundry fires and a consuming plague’2.

University of Leicester Special Collections. Revelation 13:18 from: The Byble in Englyshe : that is to Saye the Content of All the Holy Scrypture, Bothe of ye Olde and Newe Testament …, (London, 1539), SCD 00206. In this translation, the text reads: ‘Let hym that hath wytt, count the nōbre of the beast. For it is the nombre of a man, and his nombre is syxe hondred, threscore and syxe.’

Suspicion as to the cause of the Fire was reflected in Pepys’ diary, as early as 5 September, when the flames still raged: ‘Discourses are now begun that there is a plot in it and that the French have done it’3, and again 2 days later: ‘The talk is rife of the French having a hand in it’4.

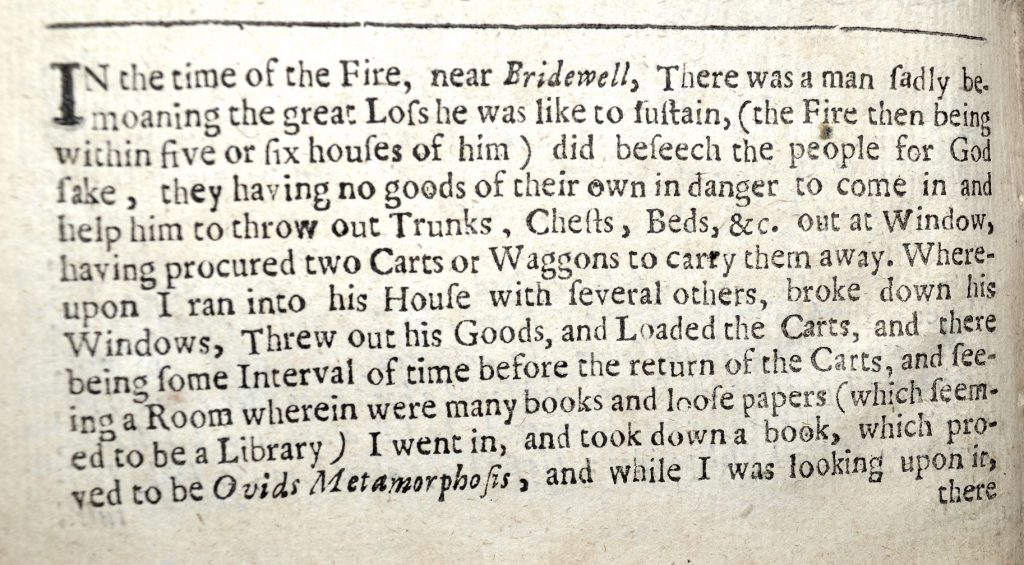

University of Leicester Special Collections. The opening passage of John Stewart’s account of his encounter with the mysterious old man, whom he accused of fire-raising. From: A True and Faithful Account of the Several Informations Exhibited to the Honourable Committee Appointed by the Parliament to Inquire into the Late Dreadful Burning of the City of London, (London, 1667), SCM 05525.

It was obviously imperative for the authorities to investigate whether there was any truth in these allegations and the Privy Council and the House of Commons both did so. The Commons set up their committee of 70 members on 25 September. One of the witnesses to appear was John Stewart, who gave an account of his experience, while attempting to save the contents of a house in Bridewell, threatened by the fire. The householder pleaded for help, ‘whereupon I ran into his house with several others, broke down his Windows, Threw out his Goods, and Loaded the Carts’5. We can only assume that the danger from the flames was not too immediate, because, while waiting for the carts to return to be reloaded, Stewart wandered into the house’s library and started to browse through a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphosis! This dramatic account follows:

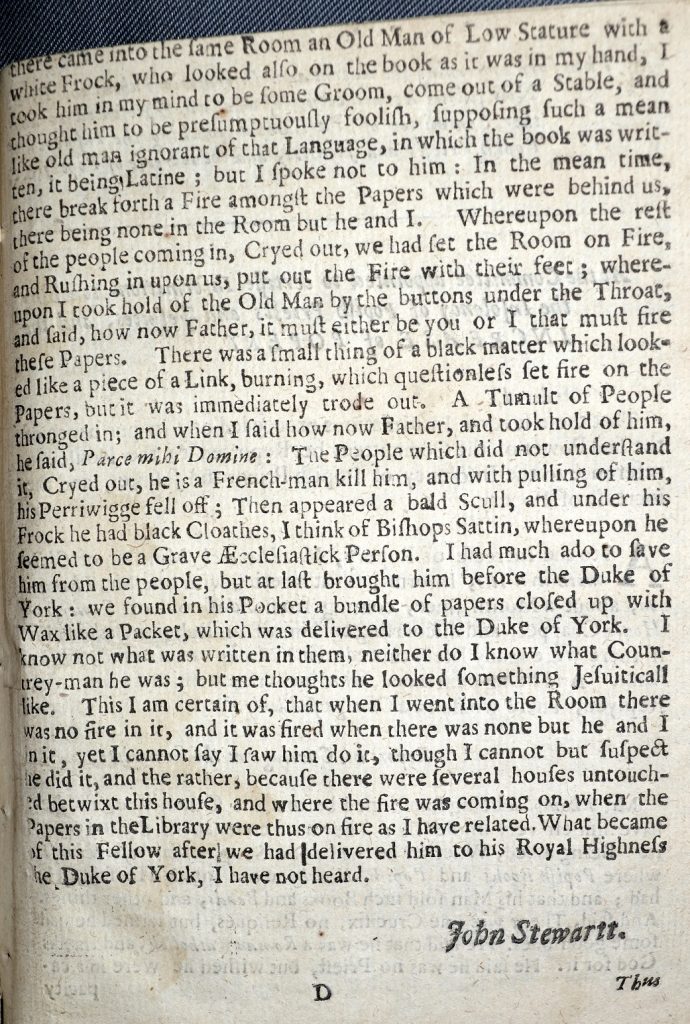

University of Leicester Special Collections. The continuation of Stewart’s evidence to the Committee. From: A True and Faithful Account of the Several Informations Exhibited to the Honourable Committee Appointed by the Parliament to Inquire into the Late Dreadful Burning of the City of London, (London, 1667), SCM 05525.

‘There came into the same Room an Old Man of Low Stature with a white Frock, who looked also on the book as it was in my hand. I took him in my mind to be some Groom, come out of a Stable, and thought him to be presumptuously foolish, supposing such a mean like old man ignorant of that Language, in which the book was written, it being Latine; but I spoke not to him: In the mean time, there break forth a Fire amongst the Papers, which were behind us, there being none in the Room but he and I. Whereupon the rest of the people coming in, Cryed out, we had set the Room on Fire, and Rushing in upon us, put out the Fire with their feet; whereupon I took hold of the Old Man by the buttons under the Throat and said, how now Father, it must either be you or I that must fire these Papers. There was a small thing of a black matter which looked like a piece of a Link, burning, which questionless set fire on the papers … When I … took hold of him, he said Parce mihi Domine: The People which did not understand it, Cryed out, he is a French-man kill him, and with pulling of him, his Perriwigge fell off; Then appeared a bald Scull and under his Frock he had black Cloathes, I think of Bishops Sattin, whereupon he seemed to be a Grave Æcclesiastick Person.6’

With great difficulty, Stewart extracted the old man from the clutches of the mob and brought him before the Duke of York. James Duke of York, brother of King Charles and the future James II, had been put in charge of fire-fighting operations on 3 September and approached this daunting task with energy and resourcefulness, attempting to keep public order and to rescue foreigners from the mob. ‘The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the fire’, wrote John Rushworth on 8 September7. In the old man’s pocket, was found ‘a bundle of papers closed up with Wax like a Packet’ and this was given to the Duke.

‘I know not what was written in them,’ Stewart concludes, ‘neither do I know what Countrey-man he was; but me thoughts he looked something Jesuiticall like’8. He admits that he cannot be certain that the old man started the fire in the room, because ‘I cannot say I saw him do it, though I cannot but suspect he did it’. The old man’s fate after his interview with the Duke of York is unknown.

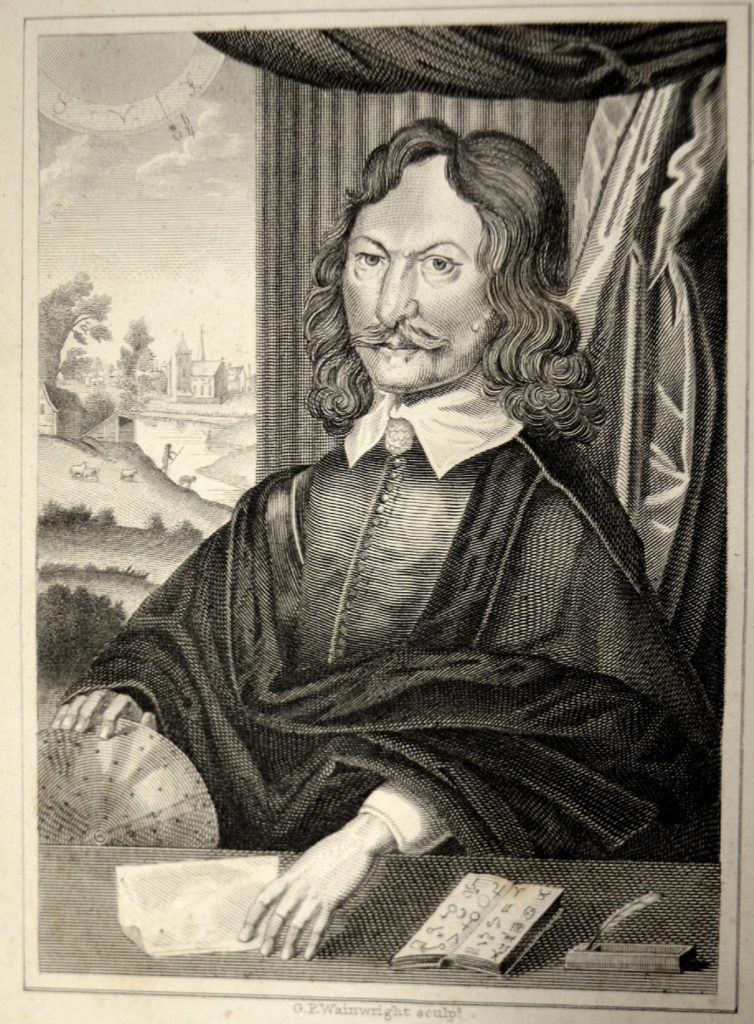

The Parliamentary Committee summoned William Lilly on 25 October to ask ‘if you can say any thing as to the cause of the late fire, or whether there might be any design therin. You are called … because in a book of your’s … you hinted some such thing by one of your hieroglyphics’9. Lilly was able to allay their concerns by his tactful response that, ‘I conclude, that it was only the finger of God; but what instruments he used thereunto, I am ignorant’10.

That same month, Thomas Osborne, a member of the Committee, wrote, ‘I have been this afternoon employed in the committee of examining persons suspected of firing the City, but all the allegations are very frivolous and people are generally satisfied that the fire was accidental’11. So the official reaction was much more measured, but, in spite of this, the popular belief persisted that the Catholics were to blame for the Fire.

- Adrian Tinniswood, By Permission of Heaven : the Story of the Great Fire of London, (London, 2004), p. 21, 942 LON TIN

- Ibid. p. 23

- Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Clerk of the Acts and Secretary to the Admiralty, Vol. 5, (London, 1920), p. 435, FAIRCLOUGH DL PEP

- Ibid. p. 429

- A True and Faithful Account of the Several Informations Exhibited to the Honourable Committee Appointed by the Parliament to Inquire into the Late Dreadful Burning of the City of London, (London, 1667), p. 24, SCM 05525

- Ibid. p. 25

- Adrian Tinniswood, By Permission of Heaven : the Story of the Great Fire of London, (London, 2004), p. 80, 942 LON TIN

- A True and Faithful Account of the Several Informations Exhibited to the Honourable Committee Appointed by the Parliament to Inquire into the Late Dreadful Burning of the City of London, (London, 1667), p. 25, SCM 05525

- William Lilly, William Lilly’s history of his life and times, from the year 1602 to 1681, (London 1822), p. 218, SCM 10949

- Ibid. p. 220

- Colin Haydon, Why was it claimed that the fire was started by a Catholic conspiracy?, The Great Fire of London: Myths and Realities, Proceedings from a study day held on 6 October 2007, p. 6, http://archive.museumoflondon.org.uk/museumoflondon/Templates/microsites/generic/article.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7B40600C41-AEFB-4BFB-89CA- BD878DE9A4DF%7D&NRORIGINALURL=%2FLondons-Burning%2Fproceedings%2F&NRCACHEHINT=NoModifyGuest

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Subscribe to Margaret Maclean's posts

Recent Comments