©Luigi Ghirri—‘Cala Paura, Polignano’ (1987)

©Nancy Goldring-Photograph, Polignano, 2012

© Nancy Goldring-Photograph, Polignano, 2012

Last year just before leaving Polignano al Mare in Puglia where I had gone to draw, I realized I hadn’t visited the one small museum in town – the Pino Pascali. Among the works in the collection I was surprised to encounter a dark and strange photograph which I immediately recognized as a work of Luigi Ghirri. The photograph revealed a Polignano hidden beneath the bright sunny skies and picturesque village with its quiet cafes. I troubled over what the photograph seemed to reveal about the place. Ghirri had focused on a small cluster of houses, illuminated by a soft light glowing within an impenetrable inky black world.

Here the isolated building is shown cut off from the old town which presides over the sea from a steep cliff. What came immediately to mind as I pondered Ghirri’s take on Polignano was Anthony Vidler’s notion of the uncanny. In his seminal study The Architectural Uncanny, published in 1992. Vidler describes the uncanny as:

‘sinister, disturbing, suspect, strange, fostering dread rather than terror, deriving its force from its very inexplicability, its sense of lurking unease rather from any clearly definite – source of fear – an uncomfortable sense of haunting rather than a present apparition.’

He cites Freud’s definition:

‘“beyond ken” – beyond knowledge – from “canny” meaning possessing knowledge rather than skill.’

As I studied the photograph, Vidler’s description seemed apt – for while these simple houses in the fishing village might have seemed ordinary – and even familiar, through Ghirri’s eyes they assume an unfamiliarity – almost the way some long-time friend after many years of intimacy, might suddenly reveal a new and disturbing aspect that alters our perception of their character indelibly. We perceive them as both familiar and yet uncomfortably estranged.

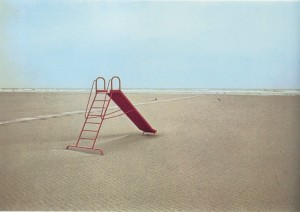

When compared with some of Ghirri’s other photographs of seaside locations, we sense the wide range of his complex approach to image-making. He had a subtle way of detecting and depicting the threshold between the natural landscape and the human presence, often allowing only a tiny remnant from an event or activity to appear in the frame. These triggering elements seem like anti-monuments – for they are human size and without gestures that command attention. Instead, they register a sense of repeated, timeless abandonment.

©Luigi Ghirri—‘Lido di Spina’ (1974)

In these beach scenes like stage sets left vacant by their actors, we might detect an uncanny of a different sort. The meagre vestiges of the human presence or activity have marked the place, changing it irrevocably. Ghirri accomplishes this transmutation – like the ‘sea change’ suffered in ‘The Tempest’ song with its haunting ring – with a minimum of information. These transforming elements, evidence of human presence, appear to have wandered casually into the viewfinder, yet they provide the clue for understanding the photograph’s meaning. Without them the image would appear to have lost its core – something would seem missing. They provide a small instance of a disquieting human incursion which, when compounded beyond the single example, implies a larger discord in our contemporary world – a cultural uncanny.

This subtly disturbing aspect is reinforced by the color scheme. In these works Ghirri has employed the bright colors of people at play – the reds and yellows of children’s toys. Soon however, the plastic brightness begins to turn sour in the way a clown‘s face elicits delight and then assumes a potentially threatening form – to cite Vidler -we have ‘the sense of the haunting presence rather than the apparition itself’.’

©Luigi Ghirri—‘Cala Paura, Polignano’ (1987)

In the Polignano works he deploys a different approach–one that engenders the photographs with a more obvious strain of the uncanny. At glance these appear to be documents – a study of place – a specific place at a specific moment. But it is Ghirri’s selection of the time and place, as well as the framing that produce the sinister feeling emitted by the works. Pipppo Ciorra, in Luigi Ghirri. Pensare per Immagini, offers insights into this process in his discussion of the way Ghirri retreats from the notion of traditional documentation:

‘Costruisce cioè un documento che è capace di sedimentare senso e di spogliarsi istantaneamente della condizione di documento.’

[…that is, he constructs a document that is capable of generating layers of meaning of instantly stripping it of the condition or notion of documentation.]

Thus the photograph becomes something else – both more and less than a mere recording. Ghirri’s retreat from documentation allows him to destabilize the images permitting other meanings to accrue and infiltrate our reading. In Luigi Ghirri e l’Architettura, Ghirri is quoted as saying:

‘Ultimately, perhaps, places are simply waiting for someone to look at them, to recognize them. Perhaps these places belong more to our existence than to modernity. They are perhaps waiting for new words or new figures.’

©Luigi Ghirri—‘Cala Paura, Polignano’ (1987)

That said, we begin to see how the uncanny seeps into the Polignano photos by casting the ordinary and the quotidian in a new light. The late Paola Ghirri writes in an interview in Vintage: ‘non lo interessa mostrare una Puglia troppo bella’ [Luigi wasn’t interested in showing a Puglia that was too beautiful.] The reassurances of the heimlich in this photo offer small comfort. I considered how and why he sought out such a dark vision – why he chose to see the village as suffused with a pervasive gloomy foreboding, almost as if in warning. The photo elicits irresolvable questions rather than providing answers. Where did the people go? Are the lights on as a beacon or merely to create a luminous safe-haven? The woman in profile so carefully framed in the window doesn’t look out into the dark world, but instead she avoids our gaze. What is she doing and what would she see if she directed her vision outwards to peer into the darkness? All of these questions lead to a larger issue: whether the darkness of these photographs in some way records Ghirri’s state of mind or is this instead one of the aspects or qualities he discerned about the place. Or might he have gravitated to places that corresponded to his state of mind? Interestingly, most Ghirri photographs seem free from the personal psychological eye.

Subscribe to Oliver Brett's posts

Subscribe to Oliver Brett's posts

Perfect example of Vidler’s uncanny!