Dr. Samantha Mitschke has been working in the School of Arts as an AHRC Cultural Engagement Fellow since February. Working with the archives held in Special Collections at the University of Leicester, she has curated a public exhibition taking place in September 2016 as part of the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of the London premiere of Loot, written by Leicester-born playwright Joe Orton.

In this blog, she discusses her response to a scrapbook of press reviews of Loot that Orton kept in his lifetime – and how it reveals a different side to his public persona.

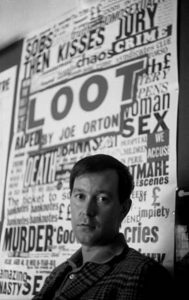

One of the most striking things about playwright Joe Orton is his apparently endless confidence. Born to working-class parents in Leicester in 1933, Orton left the Saffron Lane estate aged 17 to become an actor, decided to become a writer, and eventually exploded on to the London theatre scene in 1964 with his quirky and sexually-charged Entertaining Mr. Sloane, in which a brother and sister fight for the attentions of their bisexual lodger.

One of the most striking things about playwright Joe Orton is his apparently endless confidence. Born to working-class parents in Leicester in 1933, Orton left the Saffron Lane estate aged 17 to become an actor, decided to become a writer, and eventually exploded on to the London theatre scene in 1964 with his quirky and sexually-charged Entertaining Mr. Sloane, in which a brother and sister fight for the attentions of their bisexual lodger.

Looking through the Orton archives held at Leicester – as I have been hugely enjoying doing so over the past couple of months – swathes of items, from letters and newspaper interviews to photographs, paint a picture of a young and talented playwright facing the world with self-assured confidence. But glimpses of vulnerability and self-doubt can be seen, especially from the time when the first production of Loot flopped on provincial tour, including a defensive letter from Orton to his agent, Peggy Ramsay, and a wearily sorrowful letter to his partner Kenneth Halliwell, describing the play’s failure and asking plaintively: “Can’t you call me?”

Orton was known for his careless confidence but his private papers reveal a different side –and none more so than the scrapbook of press cuttings he kept for Loot. The first production of Loot took place in 1965 with a star-studded cast including Kenneth Williams and Geraldine McEwan. The success of Entertaining Mr. Sloane the year before had given the critics – and possibly Joe himself – high expectations that Loot would be rapturously received.

It wasn’t.

“This play makes a night to forget”, “Farce – but it’s so sick” and “Too many flat lines in this macabre farce” were just some of the headlines. The critics ranted against the language, the plot, the structure, the jokes, and even the actors’ performances. Yet Joe faithfully – and, it can be imagined, stoically – cut out every single review and pasted them into a blue-covered scrapbook, the word “Loot” on the front made from magazine letters. It’s possible that he did so as he found the outrage in them amusing – ‘outraging’ the public was his raison d’être, as evidenced by a sardonic diary entry in which he noted: “Much more fucking and they’ll be screaming hysterics in no time.” However, as a fellow writer I can only conjecture how painful those reviews must have been for him, especially after the success of Sloane. The scrapbook contains pages and pages of such reviews, yellowed with age, often accompanied by a scrawl in his handwriting where he noted the dates and names of newspapers.

Wh y did he keep such a detailed record of the play’s failure? In the previously-mentioned letter to Peggy Ramsay, Orton declared that he had never been stimulated by failure and threatened to stop writing altogether. But I believe that, no matter how cuttingly or pitilessly he judged other people – his diary is full of snarky references to acquaintances – Orton was also brutally honest with himself. Perhaps he felt that by ignoring or minimising the play’s negative reputation, he would be deceiving himself in a manner that he deliberately ‘sent up’ with the characters in his plays, many of whom have outward pretensions but refuse to acknowledge the truth of their lives. That Orton knew well enough the devastating truth of his own life is demonstrated by a small cartoon that he stuck into the scrapbook of a bear with a lump on its brow and the caption “Do you feel like a bear with a sore head?” – also suggesting an element of anger, and that he only felt able to express his anger through humour.

y did he keep such a detailed record of the play’s failure? In the previously-mentioned letter to Peggy Ramsay, Orton declared that he had never been stimulated by failure and threatened to stop writing altogether. But I believe that, no matter how cuttingly or pitilessly he judged other people – his diary is full of snarky references to acquaintances – Orton was also brutally honest with himself. Perhaps he felt that by ignoring or minimising the play’s negative reputation, he would be deceiving himself in a manner that he deliberately ‘sent up’ with the characters in his plays, many of whom have outward pretensions but refuse to acknowledge the truth of their lives. That Orton knew well enough the devastating truth of his own life is demonstrated by a small cartoon that he stuck into the scrapbook of a bear with a lump on its brow and the caption “Do you feel like a bear with a sore head?” – also suggesting an element of anger, and that he only felt able to express his anger through humour.

In 1966 Loot was staged again, with a new cast and director, and following extensive rewrites. It was a hit. Some critics still hated it, but many now saw the play for what it was – a satirical attack on society’s steadfast hypocrisy, stickling over outward morality and conventions, and blind faith in corrupt authority. The latter half of the scrapbook’s full pages are filled with critical positivity, praising all of the elements that had previously been reviled. It is easy to picture Joe smiling – with some justifiable relief – as he pasted these new reviews in for posterity. The reversal of Loot’s fortunes included the 1966 Evening Standard Award for Best Play, and Joe – with his carefully-adopted swagger, easy charm and gift for language – must have seemed to all the world that everything was going his way.

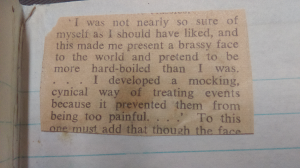

There is one final entry into the scrapbook, however, that hints at the vulnerability just beneath the confident surface. On the very last page, a small caption is pasted:

No matter what the rest of the world saw, it seems that Joe was not necessarily always as confident as he appeared – and always tried to stay true to himself.

The Loot scrapbook and other personal items belonging to Joe Orton – including the original Evening Standard award – will be on display at New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester from September 2016.

A special one-day event, “Joe Orton’s Loot: A 50th Anniversary Celebration”, is taking place at New Walk on Sunday 25 September 2016. Tickets are free but booking is essential. Email Dr Emma Parker, School of Arts for details: ep27@le.ac.uk

Website: http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/english/research/joe-orton-50-years-on

Twitter: @JoeOrtonWriter

Subscribe to smitschke's posts

Subscribe to smitschke's posts

Recent Comments