The magnificently named Lorenzo Napoleon Smith was born to Canadian parents in Massachusetts in May 1892. The family returned to Montreal in time for the 1911 Canadian census. Lorenzo signed up to the Canadian Expeditionary Force in February 1915, and by May he was in the trenches near Ploegsteert with the 4th Battalion where, notwithstanding some heavy bombardment in June, a ‘[g]eneral spirit of “live and let live” prevail[ed]’ (War Diary of the 4th Battalion, 28/10/1915).

After repeated bouts of gastritis, which he later attributed to ‘eating greasy food’ (Medical History 28/5/1918), Smith was transferred to Shorncliffe hospital in Kent in December 1915. He was sent back to Montreal for an operation and lengthy convalescence, but failed to recover his strength. Private Smith was eventually declared medically unfit for further military service in December 1916.

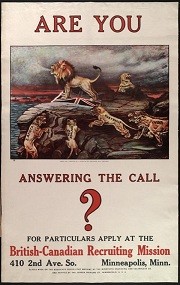

This would not be a particularly interesting story if it were not for Lorenzo’s decision to re-enlist in July 1917. He was assigned to the British-Canadian Recruiting Mission, whose function was to recruit Canadian citizens in the US through rousing speeches, plays, music and parades. These included ‘the first land-battleship ever used in the United States’: a tank called Britannia.[1] The newly promoted Sergeant Smith produced a dictionary of trench slang, called Lingo of No Man’s Land, including a foreword describing a version of his military career that was almost entirely fictitious. In this, he is presented as an American citizen who was so frustrated at his country’s failure to declare war that he crossed the border into Canada to enlist. His short front-line career, punctuated by chronic ill-health, was replaced by a year of active service with the Westmount Rifles, brought to an abrupt end by shrapnel in April 1916.

It might have been relatively easy at the time to justify a deception that helped the war effort – and clearly Smith considered that he had not done enough, because he was under no obligation to re-enlist – but it’s hard to imagine how he felt about being seen as a battle-scarred hero in later life. In 1956, when he was 64 years old, Smith requested an official record of his military service. This might have been to check whether it would undermine the account given in Lingo of No Man’s Land, but I suspect that it was to ensure that a true account was available to his wife (and children, if they had any). His posthumous confession probably wouldn’t have been clear to its recipients unless they undertook further research, but it may have been enough to salve Smith’s conscience. The measureable costs of the war were obscene enough, but we can never understand the full extent of its effect upon individual lives, which continued long after the fighting ended.

It might have been relatively easy at the time to justify a deception that helped the war effort – and clearly Smith considered that he had not done enough, because he was under no obligation to re-enlist – but it’s hard to imagine how he felt about being seen as a battle-scarred hero in later life. In 1956, when he was 64 years old, Smith requested an official record of his military service. This might have been to check whether it would undermine the account given in Lingo of No Man’s Land, but I suspect that it was to ensure that a true account was available to his wife (and children, if they had any). His posthumous confession probably wouldn’t have been clear to its recipients unless they undertook further research, but it may have been enough to salve Smith’s conscience. The measureable costs of the war were obscene enough, but we can never understand the full extent of its effect upon individual lives, which continued long after the fighting ended.

The British Library republished Lingo of No Man’s Land in March 2014, and I’ve written a new introduction to it. I’ll be talking about the dictionary at the ‘Languages and the First World War’ conference in Antwerp on the 18th of June.

[1] ‘Mission adds 46,000 to Britain’s Armies’ New York Times, 22 September 1918, p. 16.

Subscribe to Julie Coleman's posts

Subscribe to Julie Coleman's posts

Hi. I’m an ancient Leicester graduate (1966). I’ve just graduated at Wolverhampton with an MA in The History Britain and the First World War and I hope to be able to do a PhD based on the activities of the tank Britannia that you mention. This tank visited over forty towns, cities and military camps in North America including Washington, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Montreal and Toronto As well as recruitment duties she also sold millions of war bonds, helped train rookie US troops and generally raised morale. The recruitment commission also recruited British citizens living in the USA as well as Canadian. A significant number of Armenian and Jewish recruits were also obtained – these were sent out to Palestine to join General Allenby’s army. Newspaper interviews with the tank’s crew reveal that they too were quite happy to spin yarns about their service with the tank in France which were also pure fiction