On Saturday 25th January 2014, the whole group met for the first time at Leicester Central Library to discuss Brideshead Revisited. This is a novel whose reputation goes before it, and those of us who hadn’t encountered it before didn’t know what to expect – but nevertheless knew they didn’t quite get what they were expecting. Some found the characters unsympathetic, though Sebastian came out well. Even more surprising was the thought that, when the book was first published in 1945, it was accused of being Catholic “propaganda”. Why, some of us wondered, when most of the characters end up miserable?

That question led us down a theological pathway, taking in as we went the idea that, for Waugh, faith might have been a matter of surrender or succumbing to the inevitable rather than a source of unbridled joy. This could be the message behind two of the novel’s most striking metaphors (and there are many, many metaphors): the wayward Catholic called back to God witha ‘twitch upon the thread’ and the fur trapper tidying his hut in blissful ignorance that, outside, an avalanche gathers that will crash down the mountainside and engulf him.

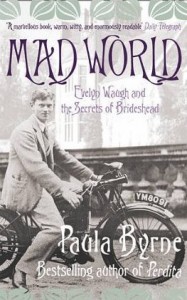

Ian brought along a copy of Paula Byrne’s marvellous Mad World, a chronicle of Waugh’s friendship with the Lygon family on whom the Flytes are apparently based. This led us to discuss how much of Waugh’s work is drawn from life, and prompted us to choose Decline and Fall (1928) as our next book. This is Waugh’s first published novel, which has its roots in the screamingly funny diary the writer kept whilst working as a schoolmaster at Wales’ unspectacular Arnold House.

We also debated the nature of Charles’ relationship with Sebastian and, subsequently, with Sebastian’s sister Julia. Generally it was felt that Julia was a pale shadow of a character compared to her younger brother, with some suggesting that Charles was only interested in her – however subconsciously – as a poor substitute for his first love. Others viewed the young men’s relationship more symbolically, believing its beauty and purity to stem from the innocence and possibility of youth. The more worldly, careworn Julia was a fitter companion for Charles’ own, cynical, middle years.

Geoffrey gave us a unique insight into youth at Oxford, comparing his experiences as an undergraduate just after WW2 with Sebastian and Charles’ in the novel. He spoke of the difficulty ex-servicemen had in returning to a university culture after war and national service life, but remembered them mixing happily enough with boys fresh from school. And while Oxford was again experiencing a post-war explosion of decadence and misrule, there was a crucial difference between Geoffrey and Charles’ experience. By the time Geoffrey began his studies, women were becoming a small but ever more visible part of undergraduate life. The boys’ club of the twenties was beginning, just, to open up.

The Waugh Book Group is open to all ages and all backgrounds, and everyone brings a unique perspective to the books we read. If you’d like to join us, please email waughbookgroupleicester@gmail.com.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Here’s a response from Elizabeth-Anne, who couldn’t make the group this month:

Sadly I was unable to attend this session I was unwell; I would have liked to talk to you all! It’s interesting that there were people who had not read the book before – my opinions have changed a lot over the 12 years since I first did. I was somewhat horrified on that occasion that someone could advocate unhappiness and found ‘the twitch upon the thread’ to be threatening rather than consoling. But in time I came to realise that for the characters, any alternative would actually have left them becoming more unhappy. Having said that I still don’t think it is a persuasive argument for Catholicism to people who are less naturally pessimistic than Waugh!

Re. how much of Waugh’s work is based on real life – I think people are fascinated by his ‘set’ even if he himself was never truly a part of the Bright Young People. This can lead people to over-emphasise how much in his work is autobiographical – some may be but it can be a dead end to try and match up characters to their ‘real life’ counterparts. Having said that it’s worth bearing in mind that Sebastian was apparently partly based on Alistair Graham – a university friend who Waugh had what seems to be a romantic relationship with – to the point that the manuscript sometimes has his name in place of the characters’ by mistake. In some ways Sebastian is an idealised personification of youth (although he is clearly very troubled from the start) but the more personal feelings are important too when considering the queer subtext – something the recent movie adaptation almost completely ignored by making the affection between the two men one-sided.

I think Julia is an underrated character – her “hysterical” speech in the grounds of the house about her still born baby is incredibly moving. I also find the account of her relationship with Rex very convincing and sympathetic – as a young woman her priority seems to have been to get away from her family, only to find that the man she thought would provide her with an escape was actually shallow and stupid. I think her relationship with Charles is another attempt at escape, in a way, and think that he loves her more than she loves him. One of the aspects I most admire about Waugh is despite the fact he can be equally nasty to everyone he can also be surprisingly empathetic to a wide range of people.