A swift and deliberate change in tone for the Book Group this month as we swapped the lyrical nostalgia of Brideshead Revisited for the cruel humour of Decline and Fall.

Evelyn Waugh’s first novel follows the fortunes of Paul Pennyfeather, sent down from Oxford through no fault of his own and condemned – or so it seems – to a life of obscurity as an assistant master at a public school in Wales:

Between ourselves, Llanabba hasn’t a good name in the profession. We class schools, you see, into four grades: Leading School, First-rate School, Good School, and School. Frankly,’ said Mr Levy, School is pretty bad. I think you’ll find it a most suitable post.

Opinion was divided on just how “funny” this novel actually was. Some of the group struggled with its apparent lack of sympathy for its characters. Margot Metroland, Chokey and Captain Grimes are grotesque, outrageous and immoral rather than realistic. Or are they? Skim off the froth, and we discovered some surprising depth to Decline and Fall and its cast.

Take Otto Silenus, for example, the modernist architect who believes that the perfect building would be one impossible to live in. He is a caricature, but also delivers a speech to Paul that struck all of us with its wisdom and perception:

It’s like the big wheel at Luna Park… [everyone is] trying to sit in the wheel, and they keep getting flung off…the nearer you can get to the hub of the wheel the slower it is moving and the easier it is to stay on.. at the very centre there’s a point completely at rest… I’m not sure I am not very near that point myself… Lots of people just enjoy scrambling on and being whisked off and scrambling on again… Then there are others, like Margot, who sit as far out as they can and hold on for dear life and enjoy that. But the whole point about the wheel is you needn’t get on at all… Now you’re a person who was clearly meant to stay in the seats and sit still and if you get bored watch the others.

It’s like the big wheel at Luna Park… [everyone is] trying to sit in the wheel, and they keep getting flung off…the nearer you can get to the hub of the wheel the slower it is moving and the easier it is to stay on.. at the very centre there’s a point completely at rest… I’m not sure I am not very near that point myself… Lots of people just enjoy scrambling on and being whisked off and scrambling on again… Then there are others, like Margot, who sit as far out as they can and hold on for dear life and enjoy that. But the whole point about the wheel is you needn’t get on at all… Now you’re a person who was clearly meant to stay in the seats and sit still and if you get bored watch the others.

We discussed Otto’s new interpretation of the Wheel of Fortune at some length, reading into it a critique of the society Waugh moved in during the 1920s and his own ambivalent position within it. Born middle class and suburban, Waugh was a stranger to both the centre of the wheel and its fast-moving edge. Was he a watcher, then, the observer who had a good laugh at everyone trying to cling on to the ride, or a scrambler who kept getting flung off?

Otto’s insight also helped us to think about Paul Pennyfeather, our “hero” for the things that happen to him rather through any agency on his part. He is, like many Waugh protagonists, a cipher. Otto goes on to suggest that humans should be classified as ‘dynamic’ or ‘static’ – and Paul, who is happiest when in solitary confinement, is as ‘static’ as they come. Is he likeable? Most of us thought not, and Ian even went so far as to suggest him as a prototype for Charles Ryders’ self-satisfied cousin Jasper in Brideshead Revisited.

There also discussed another link between these seemingly very different novels: both feature a distant and gleefully perverse father figure. In Brideshead, Charles’ father takes pleasure in punishing his spendthrift ways by making him endure dinners at home with “friends” so boring even their host is glad to see them leave. Similarly, Paul’s guardian uses his ward’s disgraceful exit from Oxford as an excuse to spend his allowance on his daughter’s wedding dress.

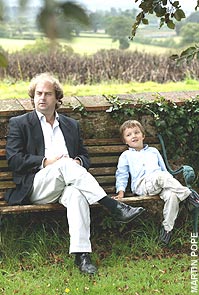

Without wishing to relate everything, necessarily, to biography, we did reflect on what such portrayals might reveal about Waugh’s own family circumstances. It’s certainly true that he was bitter towards his father Arthur, irked by his theatrical behaviour and resentful of the strong bond that existed between Arthur and Evelyn’s older brother Alec. But Arthur wasn’t malevolent. To find the kind of schadenfreude exhibited by Charles’ father and Paul’s guardian, one has to go a generation further back. Evelyn’s sadistic grandfather, known as ‘the Brute’, once deliberately crushed a wasp into his wife’s forehead to make it sting her. Evelyn’s own cruel humour pales in comparison and such is the strength of feeling towards the Brute amongst the present generations of the Waugh family that his great, great, great grandson Bron spat on his grave at the tender age of six.

Decline and Fall is farcical and cruel, but it is also complex. We glimpsed here a technique, which will become familiar to us as we journey further into Waugh’s literature, of using one sentence or even just a few words to cut through an apparently frivolous atmosphere and bring us up short against something altogether more profound. For example while, the drunken and doubt-ridden Mr Prendergast is ridiculed throughout the narrative, Waugh also grants him a single moment of humanity. When Paul invites him out for a ‘binge’ with Captain Grimes, he is taken aback by his gratitude:

‘Really, Pennyfeather… I don’t know what to say… I can’t remember when I dined at an hotel last. Certainly not since the war. it will be a treat. My dear boy, I’m quite overcome.’

And, much to Paul’s embarrassment, a tear welled up in each of Mr Prendergast’s eyes, and coursed down his cheeks.

It’s as if, having encouraged us to laugh at ‘Prendy’, Waugh performs an about-face and berates us – and Paul – for doing just that. Mr Prendergast’s tears, Otto’s insight and – later –Peter Pastmaster’s drunken nihilism prevent us from taking the farce seriously. We read passages today that made us laugh out loud, but there is pathos in this absurdity and an odd species of compassion too. Perhaps, in later novels, these modes mesh together more smoothly. We’re looking forward to finding out.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

I’m glad you’ve included the illustrations here Barbara, because I completely forgot at book group to mention how much I’d enjoyed them!

Funnily enough, a first edition with Waugh’s own cover design is up for auction soon if anyone has a spare £4,000: http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/21761/#/MR0_length=10&MR0_category=list&k0=168&m0=0.

Decline and Fall is not one of my favourite Waugh novels, but the discussion within the book group opened up a number of points I hadn’t considered.

We’re taking a huge leap at the next meeting, February had us “enjoying” his first novel, March provides us with his last…

Who needs chronology?

Quite so Ian – we’re doing a sort of whistle stop tour at the moment! We could carry on like this and do A Little Learning – Waugh’s autobiography – or go back to the beginning and work through. Let’s see how we go. We’re certainly not going to run out of material any time soon…

So glad you came to discuss Decline and Fall despite your mild antipathy. I really enjoyed the conversation too. Thanks also for agreeing to write next month’s report 🙂

Lovely to meet you all and discuss so many topics! All this and cake too.

Glad you can post, now Elizabeth…

Sorry to ask such a crass question, but I can’t seem to find the answer anywhere on these webpages.

Do you know when the new Decline and Fall is going to be published and available for sale, and what its price will be?

I ask because I need a new copy of Decline and Fall, and though I’d like to start collecting at least some of the new Complete Works series, and replace some of my old, crumbling Little, Brown editions, if Oxford University Press is going to be asking hundreds of dollars per volume, as it has with some of its other “Complete Works” series, there’s no sense waiting for volumes I won’t be able to afford.

Thanks!

Morning Richard

Not to worry at all!

I don’t know the exact price as it’s set by the publisher. It will be as that’s on a par with OUP’s ‘Complete Works’ volumes, so probably not one to read in the bath. I doubt it will run into the hundreds though!

Decline and Fall won’t be in the very first batch, which will be published late summer next year. The first ones out are likely to be Vile Bodies, A Little Learning, Rossetti, and the first volumes of Personal Writings and Essays, Articles and Reviews.

Hope this helps,

Barbara