Modernist scholar and editor of our forthcoming Black Mischief volume Dr Naomi Milthorpe has been researching with our project partners at the Harry Ransom Center. Here’s what she discovered about Penguins, Albatrosses and publishing in 1930s mainland Europe.

In November 2018 I visited the HRC, eagerly poring over their Evelyn Waugh collection materials in search of evidence to further understand the genetic, publishing, and reception history of Waugh’s African satire, Black Mischief. Published in 1932, the novel was immediately controversial, though not for the same reason as it is today. While contemporary audiences find the novel’s representation of race troubling, its major critic in 1932, Earnest Oldmeadow (editor of the Catholic weekly, The Tablet) found its depictions of adultery and cannibalism more distasteful (see Greenberg for an excellent reading of this).

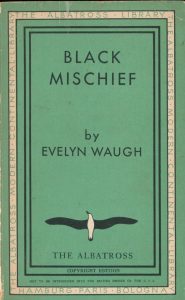

Black Mischief was Waugh’s first novel to be sold to the European firm The Albatross Press for publication on the Continent. While individual novels of Waugh’s had been published in Europe, it wasn’t until Black Mischief that Waugh enjoyed an enduring reprint relationship with a Continental publishing house. The origins of this relationship are revealed in the HRC’s collection, which includes Memoranda of Understanding between Waugh and Albatross, and a fine copy of the Albatross paperback edition of Black Mischief, first published in 1933. These materials help to form a picture of how Waugh’s novels were published and marketed on the Continent.

The Albatross Press was established in 1932 by John Holroyd-Reece and M.C. Wegner, and set about to rival Tauchnitz, then the major European reprint publisher. Lise Jaillant’s excellent book Cheap Modernism: Expanding Markets, Publishers’ Series and the Avant-Garde describes in detail the competition between Tauchnitz and Albatross for modern (and modernist) Anglophone novels. While for today’s readers the firm’s bird emblem and cheap but high-quality product recalls Penguin, Albatross is the older firm (Jaillant 109). Their first number was James Joyce’s Dubliners, and while they eagerly sought the rights to highbrow writers like Aldous Huxley, Virginia Woolf, and Katherine Mansfield, they also published mainstream and genre authors including Edgar Wallace, Hugh Walpole, Dashiell Hammett, and Warwick Deeping.

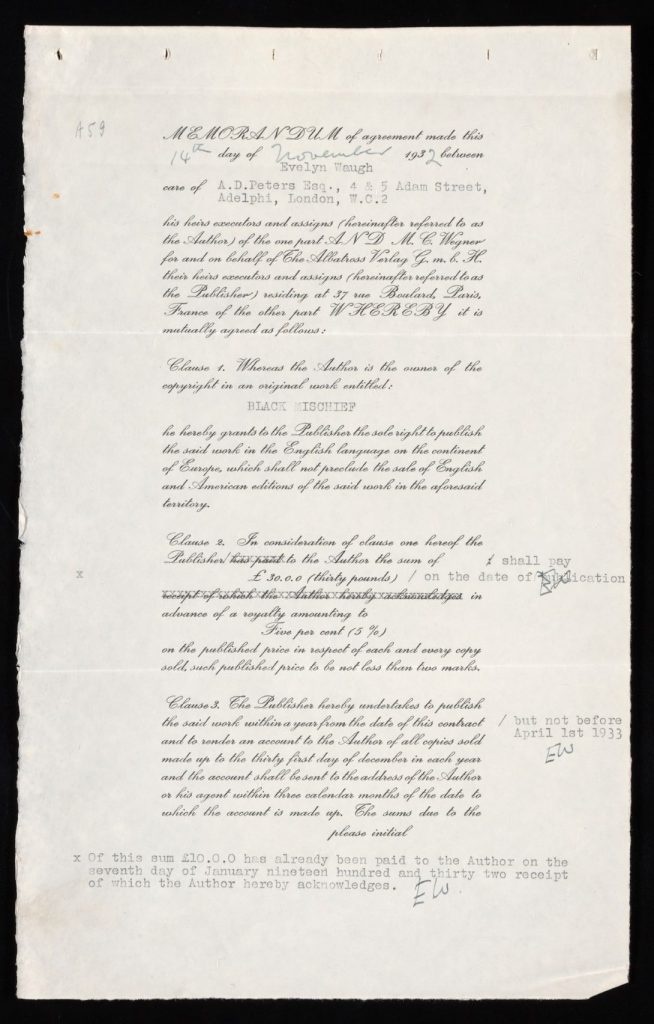

Albatross swooped on Waugh early in January 1932 – many months before Black Mischief was completed. Wegner wrote to Waugh’s agents offering to option Waugh’s next novel, “or should the said novel not prove suitable […] ‘Remote People’.” (7 January 1932, Box 139 (1932), A.D. Peters Correspondence) The agents eagerly accepted, writing to Waugh that they had “persuaded the publishers who call themselves The Albatross Press, and who are Tauchnitz’s only rivals on the continent, to pay Ten Pounds (£10) down” (8 Jan 1932, Box 139 (1932), A.D. Peters Correspondence). Letters and postcards went back and forth between the agents and Albatross throughout 1932. Sometime in early October, Roughead sent Albatross an advance copy, and on October 25 Wegner wrote back to negotiate for the novel’s publication by Albatross in April 1933, saying he found the novel “delicious” (Box 139 (1932), A.D. Peters Correspondence). Albatross sent a “Memoranda of Understanding” which Waugh signed from Easton Court Hotel, Chagford, in November 1932, a few weeks prior to his sailing for South America (Box 139 (1932), A.D. Peters Correspondence).

In March 1933 Albatross sent a cheque for £20, making up the £30 advance promised in the MOU. This extra money would have been welcomed by Waugh, who had cash flow problems at the time. On April Fools Day 1933, Black Mischief was published, no.59 in the Albatross Modern Continental Library.

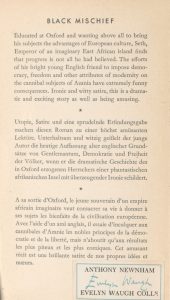

Albatross were distinguished from Tauchnitz in using a “colour system” to categorise publications by genre (again, anticipating Penguin): red for adventure and crime, blue for romance, purple for biography, yellow for psychological novels and essays, orange for short stories and humorous or satirical works. Black Mischief is green – that is, according to the Albatross key, “stories of travel and foreign peoples.” That Waugh’s novel should be categorised in travel (rather than satire) reveals the way Albatross marketed the book to European readers. The blurb, given in English, French and German on the inside front cover, emphasises the book’s exotic imaginary African location, while at the same time making clear its status as a satire.

As Jaillant comments, the text of these blurbs “sometimes varied significantly, reflecting national taste and cultural expectations.” (110) The German version for Black Mischief is particularly interesting, given the political contexts of Germany in 1933. While naming the novel a “Utopia”, the second sentence declares that “the young author criticizes today’s view of the old English principles of gentlemanly humility, democracy and freedom of the people”. The HRC’s Peters correspondence shows that German firms were particularly keen on securing translation rights for this novel, which caustically satirizes democratic ideals like “proportional representation, women’s suffrage, independent judicature, freedom of the press” as simply things that have “ceased to be modern” (Waugh 164).

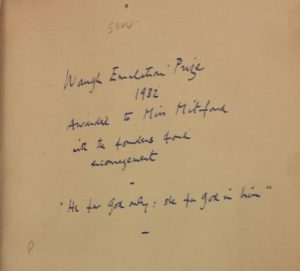

At the same time as Albatross published their books in affordable paperback, they also produced handsome presentation copies. This appealed to Waugh. In a letter to Wegner dated 19 June 1933, and written on Savile Club letterhead, Waugh wrote that he had returned from South America “to find waiting for me the charmingly bound copy of BLACK MISCHIEF. It is a great delight to me to be published by your firm, particularly when I see how admirably the edition is produced.” He surely would have been describing not the paperback, but their limited presentation edition on handmade paper, bound in green half-leather and cloth and limited to 12 copies. One copy Waugh made out to Nancy Mitford and inscribed as the “Waugh Emulation Prize” (a joke about Mitford’s Highland Fling, which had been compared by reviewers to Vile Bodies), is now housed in the Huntington Library’s Evelyn Waugh collection.

Figure 4. Nancy Mitford’s “Waugh Emulation Prize,” Black Mischief, Albatross limited edition, Huntington Library

As Jaillant suggests, Albatross’s simultaneous production of paperbacks and high-quality presentation copies “positioned [the firm] as a luxury brand for a broad audience.” (109) Explicitly marketing their books as modern, Albatross sought to appeal to a cosmopolitan audience with a taste for both the avant-garde and more mainstream fare. As a modern satirist, Waugh (then as now) fit somewhere in between these two poles. Notably, Black Mischief represents something of a turning point for Waugh: it was the first novel after the wildly successful Vile Bodies, so expectations were high. But the early thirties were a time of mixed success for the author. Remote People wasn’t a raging hit – many reviewers called it dull – and magazine editors complained throughout 1932 and 1933 that his writing wasn’t up to scratch (Stannard 343). When he began writing Black Mischief in 1931, under the title “Accession”, Waugh wrote to Roughead assuring him that it would be a “a real dyed in the wool best selling novel” ([July 1931], Box 138 (1931), AD Peters Correspondence). Although the novel was reasonably well-received, Waugh didn’t get the ‘hit’ he had hoped for.

Black Mischief was the first of Waugh’s novels to be published by Albatross, but it wasn’t the last. The HRC has several more MOUs showing Waugh’s continuous publication by Albatross throughout the thirties and right through to Brideshead Revisited, suggesting Waugh continued to appeal to Continental readers. Albatross would have found Waugh new readers on the Continent, and may have helped further establish his reputation at a critical moment in his career.

Works Cited

AD Peters Correspondence, Boxes 138-139. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Memoranda of Understanding, Evelyn Waugh Collection, Box 13 fol.13, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center.

Greenberg, Jonathan. “Cannibals and Catholics: Reading the Reading of Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief.” Modernist Cultures, vol. 2, issue 2, 2006: pp.115-137.

Jaillant, Lise. Cheap Modernism: Expanding Markets, Publishers’ Series and the Avant-Garde. Edinburgh UP, 2017.

Stannard, Martin. Evelyn Waugh: The Early Years 1903-1939. J.M. Dent, 1986.

Waugh, Evelyn. Black Mischief. Chapman & Hall, 1932.

— Black Mischief. Albatross, 1933. Anthony Newnham Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center.

— Black Mischief. Albatross, 1933. Inscribed author copy, Evelyn Waugh Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino.

Subscribe to 's posts

Subscribe to 's posts

Recent Comments