The following is a guest post kindly supplied by Duncan McLaren.

In the spring of 2011, when my book Evelyn! Rhapsody for an Obsessive Love was listed for publication by the now defunct Beautiful Books, Alexander Waugh kindly provided me with scans of several photos that he suggested I might use for publicity purposes. I have since pored over these precious images, extracting as much as I can from them, and in this blog I want to tell a Waugh readership about the above, previously unpublished, photograph. At first glance an unremarkable interior? I hope you’ll think otherwise by the end of this piece.

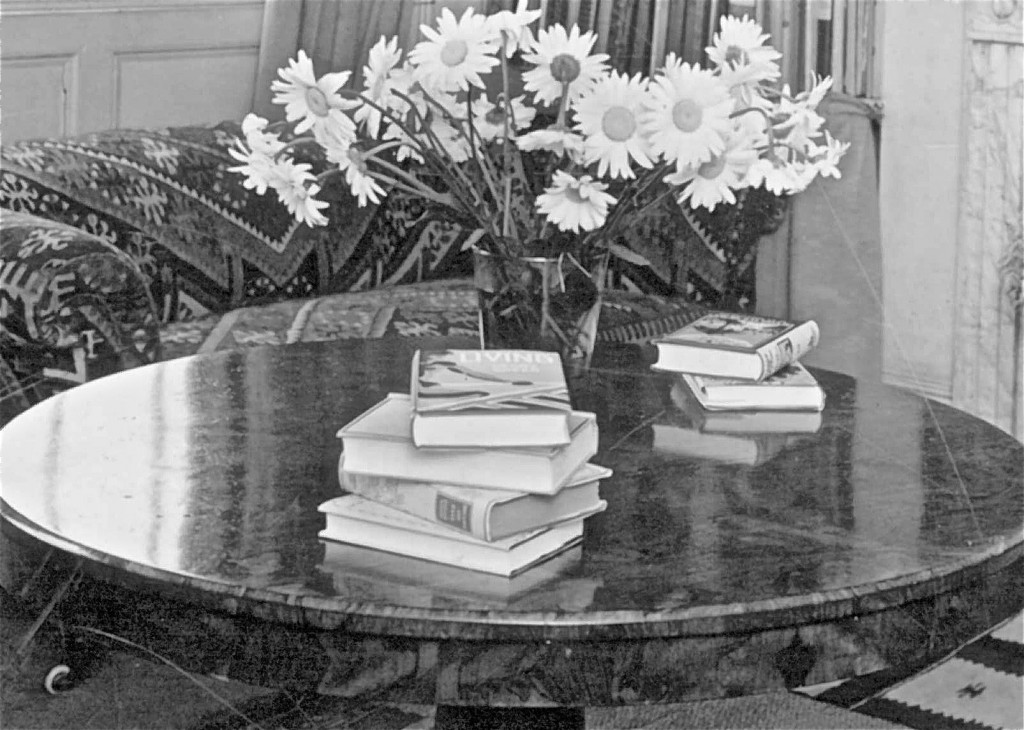

It’s a picture of the living room at 17a Canonbury Square, the flat that the Waughs moved into after marrying in the summer of 1928. When Decline and Fall came out in the autumn of that year, the Evelyns entertained in their Islington flat Mr Arnold Bennett and Cyril Connolly, both of whom had just reviewed Waugh’s sparkling first novel with obvious delight.

But it’s Vile Bodies, Waugh’s second novel, that the above picture gets to the heart of. At the beginning of June, 1929, the Waughs had just returned to the flat after a near-disastrous cruise of the Mediterranean that Waugh would later write about in Labels. While she-Evelyn, who had been dangerously ill during the cruise, dived back into her London social life, he-Evelyn retreated to the Abingdon Arms, a pub in Beckley, near Oxford, in order to write his second novel. Before he left London, Waugh read Living by Henry Green, the pen-name of Henry Yorke who Waugh had known at Oxford and whose writing he already knew and admired. That’s Yorke’s book resting on the top of the main pile on the polished table in the Waughs’ sitting room.

On June 2, he-Evelyn was writing to Yorke at length about how much he admired the portrait of working class, industrial life. He especially liked the book’s dialogue, and commented that Yorke had made a new artistic form out of it. Waugh went so far as to quote three sentences that he particularly admired from the book, so let’s highlight them now:

‘But it is quite true to say that there was nothing dirty in all this.’

‘Dropping suddenly to be intimate.’

‘He spoke like he was sorry Lil was as she was.’

An interesting selection given that Waugh was about to write about the relationship between Adam and Nina in Vile Bodies using distilled dialogue.

In the letter to Yorke, he-Evelyn went on to say that while he was writing his new book in a pub, she-Evelyn was going to be living in the flat at Canonbury Square with Nancy Mitford for company and that Henry should visit them. Waugh also mentioned that he and his wife came back to bills of over £200 and that both of them were already overdrawn at the bank.

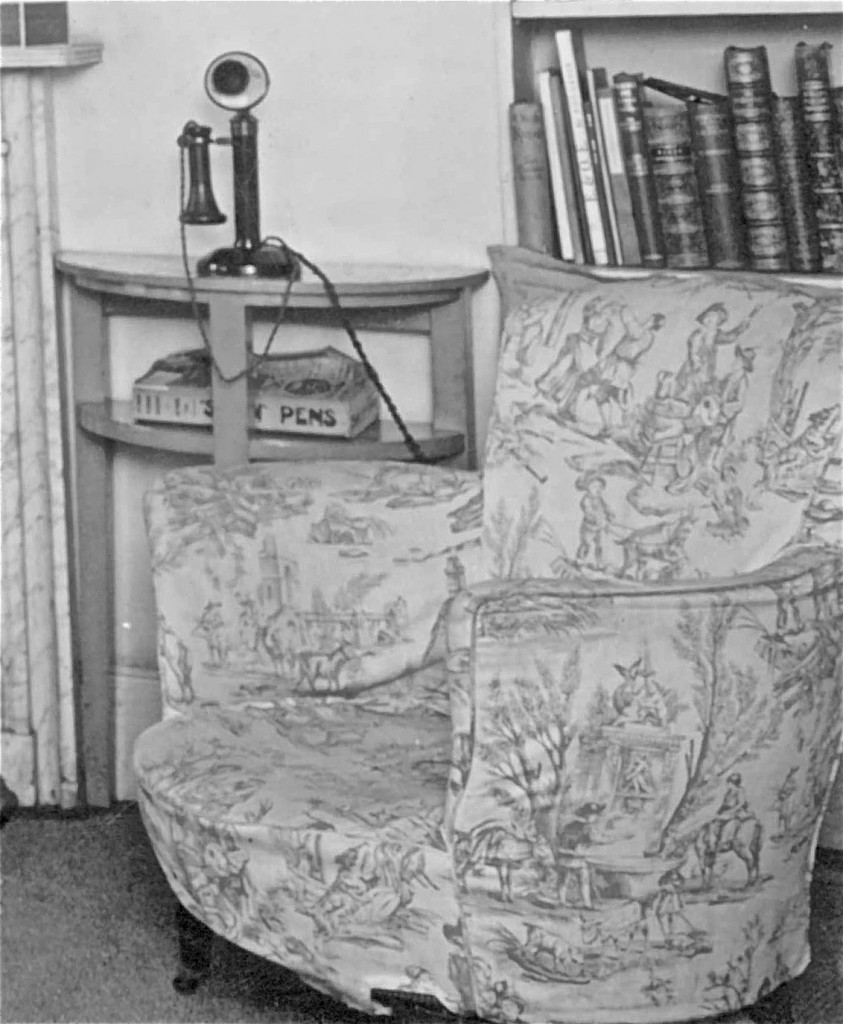

Vile Bodies concerns Adam Fenwick-Symes who has just come back from a cruise and who needs to write a book or in some other way come into money. At the end of chapter two, Adam phones Nina, to whom he is engaged. These phone calls become a motif in the book, and one can see why. On one end of the line, he-Evelyn, ensconced in the Abingdon Arms, On the other end of the line, she-Evelyn. Thanks to the photograph of the Evelyns’ living room, one can picture She-Evelyn with her bum parked on a nice bit of Arts and Crafts upholstery, the pattern showing rural scenes involving trees, churches, peasants and farmyard animals.

The phone rings at 17a Canonbury Square, June 1929. Perhaps Nancy answers it. Perhaps she-Evelyn answers it, pretending she doesn’t know who’s asking to speak to Mrs Waugh. Selina Hastings, one of Waugh’s biographers, tells the story of how, shortly after the Evelyns had first met in 1927, he-Evelyn – piqued at not being given permission to walk she-Evelyn home – phoned her at 1.30am and said: “Is that Miss Gardner?” “Yes.” “What I want to say is, Hell to you!’ before replacing the receiver. In Vile Bodies, the first exchange goes:

“May I speak to Miss Blount, please?”

“I’ll just see if she’s in.” said MIss Blount’s voice. “Who’s speaking, please?”

“Mr Fenwick-Symes.”

“Oh.”

“Adam, you know… How are you Nina?”

In any case, using the above image, picture a seated she-Evelyn taking up the main part of the phone in her right hand and putting the ear-piece to her left ear. Evelyn, having had to put his pint and his pipe on one side to make the call, tells her how his writing is going. And she tells him about her newly resurrected social life. As well as Nancy, she is seeing a lot of John Heygate, Eleanor Watts and Tony Powell. Together, they are going to all sorts of parties. “Too, too drunk-making,” concedes she-Evelyn.

The book under the candlestick phone is presumably a phone directory. Along the spine are the words “SWAN” PENS, an advertisement for a leading fountain pen of the time, perhaps the same kind of pen as Evelyn was writing his new novel with. He-Evelyn sent the new novel in weekly batches to she-Evelyn, and she would arrange for the words to be typed up. Are you getting the picture? Real life (he-Evelyn and she-Evelyn) and fiction (Adam and Nina) running side by side, just as is the case with so much of Waugh’s autobiographical-led work.

In the third chapter, Adam finds digs in London. Shepheard’s Hotel in Dover Street, run by Lottie Crump, bears a close resemblance to the Cavendish Hotel in Jermyn Street run by Rosa Lewis. And indeed Waugh would seem to have had this in mind. But he couldn’t escape the fact that he really was in the Abingdon Arms, and perhaps it was while drinking in the bar of an evening that he managed to come up with the comic scenes at Shepheard’s. Adam wins £500 from a bet in the bar and then doubles his money thanks to winning a toss. He phones Nina at the Ritz (where he-Evelyn proposed to she-Evelyn) to communicate the good news. Now Adam and Nina could get married! (Now the Evelyns could pay off their debts.) Adam returns to the parlour at Shepheard’s. A few minutes later, he phones Nina again to tell her he’s been persuaded by rather a drunk Major to put the money on a horse called Indian Runner. Perhaps they won’t be able to get married after all. (Perhaps the Evelyns wouldn’t be able to pay off their debts quite as soon as they’d hoped.) As I say, reality feeding the fiction. Reality being tweaked for comic effect.

‘End of book one’ Waugh wrote at the end of chapter six, surely hoping that by the time he sat down to write the second half of the book he would know where his novel was going. Because what he’d written up to that point was a warm, playful riff on his relationship with she-Evelyn and a sharp, funny critique of his generation’s party lifestyle. But it was the despair that Waugh had felt when stuck teaching at a school in North Wales that had been the driving force behind Decline and Fall. Where was the equivalent trauma that would give Vile Bodies direction and substance? Don’t worry, Evelyn, your trauma awaits you.

John Heygate had been seeing a lot of Eleanor Watts that summer. Indeed on one occasion, he drove Eleanor and she-Evelyn to spend the day with he-Evelyn in Beckley. John proposed to Eleanor at a party in the first week of July and was turned down. He stayed on at the party to drown his sorrows and ended up taking she-Evelyn back to his flat in Cornwall Gardens and sleeping with her.

A week later – the letter was dated, July 9, 1929 – she-Evelyn wrote a despairing letter to he-Evelyn at the Abingdon Arms stating that she was in love with John Heygate and didn’t know what to do. Had he-Evelyn got started on the second half of his book that week? If he did, the pages don’t survive into the bound manuscript. The way that Vile Bodies carries on is largely dictated by the shattering of his marriage.

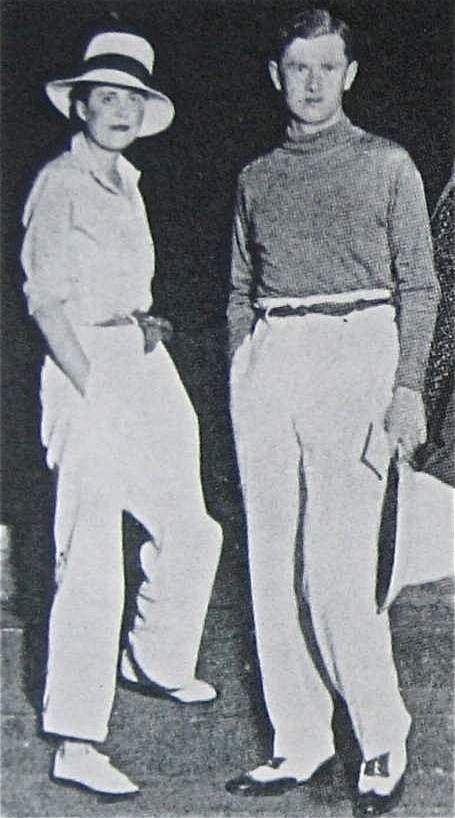

Evelyn returned to London from Beckley on July 12. Evelyn told she-Evelyn that he would be prepared to carry on as if nothing had happened on condition that she never see John Heygate again. For the next fortnight, he-Evelyn remained with she-Evelyn at Canonbury Square, escorting her to parties. There was a Tropical Party at the Friendship on July 16, where the following photograph of two miserable individuals was taken. He-Evelyn looks grim. She-Evelyn looks ill.

The fortnight of attempted reconciliation between the Evelyns did not work out. She-Evelyn met Alec Waugh at the Gargoyle (in between parties, I presume). She told him things were terrible, that he-Evelyn was drinking far too much which was making him paranoid. He’d even accused his wife of trying to poison him.

What happened at the end of the fortnight? Martin Stannard asked she-Evelyn in the 1980s. She told Waugh’s first reliable biographer that it was he-Evelyn’s decision that things were hopeless between them and that they should divorce. John Heygate and Tony Powell had gone on holiday to Germany. Powell received a telegram saying: ‘Instruct Heygate return immediately Waugh’. This was he-Evelyn requiring John Heygate to take she-Evelyn off his hands. Meanwhile, Lady Burghclere had insisted that her daughter go to Venice to think things over. However, John returned to England, got in touch with her, and she-Evelyn went to live with him at his flat in Cornwall Gardens. Martin Stannard spoke to many people about the split. In general, the Catholics were critical of she-Evelyn’s behaviour. Others were more supportive (such as Tony Powell and Alec Waugh). Stannard put the following question to those he contacted: ‘Do you think that at least as far as she was concerned, the sexual side of the marriage was inadequate?’ Most respondents felt this to have been the case.

Having sent off the telegram, Waugh did an odd thing. On July 26 he travelled north to Cheshire in the car of Eleanor Watts, a trip which Selina Hastings tells us about. He-Evelyn stayed with Eleanor for several days at her parents’ house, Haslington Hall near Crewe. There was much sympathy between them based on mutual unhappiness. Eleanor was regretting having turned down John Heygate on that fateful night in early July. She advised he-Evelyn to try and put his own loss out of his mind. ‘I can’t, I can’t’ was his repeated refrain.

According to Selina Hastings, it was while he-Evelyn was in Cheshire that she-Evelyn (she could not have been in Italy more than a day or two) was photographed with John Heygate at a party. When she asked Nancy Mitford for advice, Nancy told her to tell her husband the encounter had been an accident and that she loved only him. She-Evelyn then told Nancy that she didn’t love he-Evelyn, that she’d only married him to escape her own mother. Nancy, sensing scandal, left the Canonbury Square flat at about this time. She-Ev also told Pansy Lamb that Evelyn was too difficult to live up to. And complained to an unidentified girlfriend that he-Evelyn had been ‘bad in bed’; that she found his sexual techniques unpleasurable, techniques that had been learned in affairs with men.

No doubt some of this was on he-Evelyn’s mind when Eleanor Watts drove him back to London on August the first. He entered the empty flat and found what? According to official biographer Christopher Sykes, he found the house empty – no Nancy and no she-Evelyn – and had to go and fetch the ‘daily-woman’ to try and find out what had happened. However, according to Martin Stannard, there was no shock desertion. ‘The shock was at standing alone in the place which, only three weeks earlier, had formed the focus of an apparently serene domestic life.’

I think that he-Evelyn was indeed shocked. I suspect it’s at this moment that he took the photograph of the living room (there is a companion photograph of the dining room which has been much reproduced). I say this because of one telling detail. Eleanor Watts told Selina Hastings that when not drinking Black Velvet together at Haslington Hall, he-Evelyn – who had his paintbox with him – had been painting sketches for the dust-cover of Vile Bodies. Surely it is one of these that he-Evelyn placed in the middle of the mantelpiece in the living room before taking a photo of the room.

I should mention first about the image below, that the picture on the left edge of the mantelpiece could be the ‘crumbling Greek ikon’ that Alastair Graham gave Evelyn on his visit to Athens, Christmas, 1926. Or it could be something brought back from the spring 1929 cruise. After all in Waugh’s letter to Henry Yorke of June 20, he mentions that he’d bought a seventeenth century water colour of the Prodigal Son in Malta, and wondered if Henry would like it as a wedding present.

The striking painting in the middle of the above detail consists of a top hat above a bowler hat, with a target pattern imposed on them both. There are also letters which make up the word BOGUS. (Waugh did something similar for the cover of the Oxford Broom in 1924, there making a pattern, though not such an ambitious one, of the letters B.R.O.O.M.) The letters B, O, G, U and S may have been cut out of something, perhaps a magazine, and laid out incongruously. Now the word ‘bogus’ crops up a couple of times in the first half of Vile Bodies. But in the devastating interval before getting down to the second half of the book, the word was clearly on he-Evelyn’s mind a lot.

Perhaps he’d started Vile Bodies thinking that the world of the bright young thing was bogus; now he was going to have to come to terms with the fact that what Adam and Nina had together was bogus too. Bogus?… Us?…

In any case, he uses the word ‘bogus’ at least eight times in the second half of the novel. The most significant instance being in the following quote from the Jesuit priest, Father Rothschild:

‘”I know very few young people, but it seems to me they are all possessed with an almost fatal hunger for permanence. I think all these divorces show that. People aren’t content just to muddle along nowadays….And this word “bogus ” they all use… They won’t make the best of a bad job nowadays.“‘

The top hat is more decipherable than the bowler in the painting, but the bowler is more interesting. When Waugh takes up his book again, Adam becomes Mr Chatterbox in place of the journalist who killed himself. He introduces the green bowler as the latest ‘must-be-seen-in’ fashion accessory. The phrase ‘green bowler’ comes up at least seven times in the second half of the novel. Of course, I don’t know if the bowler in the black-and-white photograph is green or not.

I suppose that Waugh could have painted the picture (which looks rather small when one refers back to the whole image of the room) while on the cruise, and that the photograph of the living room was taken in the first few days of June. That would explain why the book, Living, was given a prominent position in the photo’s composition. But I don’t think that’s what happened. I don’t think Evelyn would have attempted to paint the cover for a book he had not yet written and barely conceived. I suspect that the high opinion that Waugh had formed of Living at the beginning of June was still there at the beginning of August and that he had space in his mind for both feelings of literary admiration and personal devastation.

This is an edited version of an article that appears on Duncan’s own Evelyn Waugh website: www.evelynwaugh.org.uk

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Recent Comments