Two fifteenth-century prelates and crusading – Piccolomini and Cusa

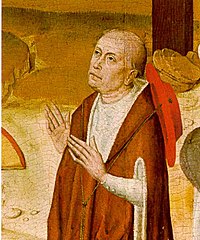

The Church produced some outstanding figures in the fifteenth century and none more so than Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (1405-64), who became pope in 1458 as Pius II, and Nicholas of Cusa (1401-64), who was made cardinal in 1448. They make for an interesting comparison. Piccolomini hailed from Corsignano, near Siena, a town which he largely rebuilt after he became pope, renaming it Pienza. He was an astonishingly versatile man, a dazzling orator and prolific author, an indefatigable networker and self-publicist without equal. His Commentaries on his own pontificate are not just a remarkable source for European political affairs in the 1450s and early 1460s, but also engagingly easy to read – not least when the pope is praising himself! It is clear that Piccolomini was suave, charming and fluent, a sort of Renaissance Bill Clinton.

Nicholas of Cusa on the other hand is a much less accessible individual. Everything is not on display, as it is with Piccolomini. He had a more incisive mind than Piccolomini and owed his success less to his ambition and determination than to his evident intellectual depth and convictions.

Nicholas of Cusa on the other hand is a much less accessible individual. Everything is not on display, as it is with Piccolomini. He had a more incisive mind than Piccolomini and owed his success less to his ambition and determination than to his evident intellectual depth and convictions.

Both men had to contend with the tensions and contradictions of a Church that was in disarray, obviously in need of thoroughgoing reform but unable to perform the necessary surgery on itself. In their youth Cusa and Piccolomini embraced conciliarism, the movement for a more open and self-critical Church, but both abandoned the conciliarists for the papalists, who accepted hierarchical centralism with all its faults. Piccolomini spilt much ink explaining and justifying his change of allegiance, while Cusa barely addressed the matter. Similarly, both men were deeply affected by the fall of Constantinople to Mehmed II in 1453. But again, their different temperaments generated different responses. Piccolomini, who owed his papal election five years later in part to his commitment to crusade, saw a unified Christian defence against the Turks as crucial if the Church were to survive and spent much of his energy in pursuing it. Cusa lacked his friend’s single-mindedness on the issue. He applied his reputation and skills alike to the great task that Pius II set the Church, but we sense ambivalence.

In fact Cusa’s most interesting response to the catastrophe of 1453 was a curious treatise called ‘The peace of faith’ (De pace fidei) in which he sought grounds for peaceful co-existence between the major world religions. It has been regarded as proof that Cusa rejected crusade, but that is going too far. It is probably more accurate to say that Cusa was unable, for mingled reasons of intellect and personality, to set aside his reservations and push for a crusade in the way that Piccolomini did. One of his most revealing statements on crusade was voiced at the imperial diet of Regensburg in 1454.

The assembly met to discuss what should be done about the Turks, and both pope and emperor backed action. But Cusa, a prince of both the Church and – as bishop of Brixen – of the Holy Roman Empire, could not bring himself simply to call for a crusade as the emperor’s secretary Piccolomini did. Instead he commented rather sourly – on the basis of a personal visit to Constantinople in 1437 – that the Greeks had brought this disaster on themselves. There may have been some truth in his remark, but it was singularly ill-timed. The last thing that promoters of a crusade needed in 1454 was doubters in their own camp.

Subscribe to Norman Housley's posts

Subscribe to Norman Housley's posts

Recent Comments