First Edition of A Tourist in Africa (1960)

Before last Saturday, I kept quiet about A Tourist in Africa’s reputation as Waugh’s ‘worst book’. Why prejudge the issue? The travelogue was specially requested by a member of the group – if he’d enjoyed it, why shouldn’t the rest of us?

In the event, we did more than enjoy it. For many of us, A Tourist in Africa changed our conception of Waugh; we only wished he’d pushed himself further over some of the urgent political and moral issues he raises –but only to half-mast – in the book.

A Tourist in Africa was written at a pivotal moment in British history. Over the decade following its publication (1960), Britain would lose all its territory in the countries Waugh visited; Kenya, Tanganyika (Tanzania), and the Rhodesias (Zambia and Zimbabwe). Waugh is anything but prophetic about these seismic political shifts, continually playing down reports of unrest and instead remarking on the peaceful atmosphere as he ambled through East Africa.

This misplaced optimism comes as no shock to the seasoned Waugh reader. Waugh had a flair for being on the wrong side of history, most spectacularly when he backed Mussolini’s cause in 1930s Abyssinia (Ethiopia). But Waugh’s insistence on the delights of these nations on the cusp of massive and often traumatic change makes more sense when you know that he was paid to write this book by Union Castle, a shipping company looking to drum up trade for its East African line. No wonder, then, that Waugh preferred sailing to its upstart cousin, flying:

It is more agreeable and, surely, healthier to come to the tropics gradually than to be deposited there suddenly by an aeroplane in the clothes one wore shivering a few hours before in London.

But this is not a straightforward puff piece. Union Castle allowed its literary promoter a fairly free hand, and while the “colonies” appear suspiciously idyllic in terms of climate and landscape, their occupants do not escape Waugh’s criticism. A writer often attacked for racism and even fascism, Waugh uses the final pages of Tourist to denounce ‘racial insanity’ with plenty of Wavian examples:

In Washington D.C., when I was last there, I visited a segregated Pets’ Cemetery. The loved ones were separated not by their own colour but by that of their owners; black and white pets of white women lay indifferently in one quarter; black and white pets of black women in another.

More painfully, Waugh tells us, ‘I heard of a Catholic woman who was offended because an itinerant priest said Mass for her on her stoep with a black server. But the story was told me as something disgusting.’

Before we get carried away with this new egalitarian Waugh, we should take note of his unique explanation of the ‘infection’ of Apartheid:

It is the spirit of equalitarianism literally cracked. Stable and fruitful societies have always been elaborately graded. The idea of a classless society is so unnatural to man that his reason, in practice, cannot bear the strain. Those Afrikaaner youths claim equality with you, gentle reader. They regard themselves as being a cut above the bushmen. So they accept one huge cleavage in the social order and fantastically choose pigmentation as the determining factor.

Hmm.

It’s not just in politics that Waugh chronicles the absurd. An encounter with the self-crowning ‘King of the World’ would be at home in one of his early comedies:

I expected a flamboyant figure from Harlem. Instead there presently emerged from the hotel an elderly white man dressed in a blue kimono. He was unattended and somewhat encumbered by paraphernalia. He gave no indication of expecting any kind of ovation. As purposeful and recollected as a priest going to his altar to say Mass, the Bishop shuffled across under the blazing sun, opened a folding chair and sat down in the garden. The police, the two journalists, Mr Thompson and I collected round him. A representative of the local broadcasting organization appeared with a tape-recorder. The Bishop ignored him and like a priest or rather, perhaps, like a conjuror, began arranging his properties. He had a bible, a crown which seemed to be light and inexpensive, a flag, not – shade of Rosenthal! – the Stars and Stripes but something simple but unidentifiable of his own design of blue and white stars, and a bladder. The stuff of his little chair was slightly regal, a pattern of red and gold with ornamental tassels. He dropped the flag over his head as though preparing for a nap. Then he blew noisily into the bladder which proved to be an inflatable, plastic terrestrial globe. He blew hard and strong, but there was a puncture somewhere. It took the form of a wizened apple but not of a full sphere. After a few more puffs he despaired and laid it on the ground at his feet.

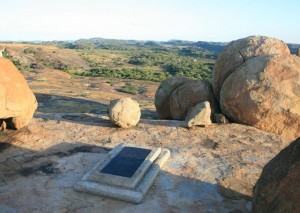

When Waugh reaches Rhodesia, Cecil Rhodes’ brand of madness is dealt with far less affectionately. The author chronicles his ‘vision’, which was ‘almost all…hallucination’ with an ambivalence as lyrical as it is unexpected.

Many of us had allowed ourselves to pigeonhole Waugh as a grumpy old conservative, reactionary and unreflective. By contrast this book, written on the fly to fulfil a contractual observation, shows a compassionate, contemplative and nuanced mind at work. If he’d worked it a bit harder, A Tourist in Africa would be a travel classic.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

By the way, ‘the Rhodesias’ are not Zimbabwe, but Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Thanks, John – I will amend.