In an upcoming court case you might just have heard of, the Daily Mail will defend its printing of Meghan Markle’s personal letter to her father Thomas. If the paper’s arguments are accepted, the ruling could have a huge impact on who we think owns what – and on the work of biographers everywhere.

Markle’s principal complaint against the Mail is that it has breached her copyright. Anyone working on collected letters, or biography, can understand this: under UK law, as it’s currently applied, Meghan would have to be dead for seventy years before anything she wrote in a private capacity could be published without the express permission of her estate. It’s the same law for everyone, rich or poor, artists and accountants. It causes numerous headaches for the likes of us. On the Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh we are lucky enough to work closely with the Waugh estate. Evelyn’s grandson, Alexander, is our General Editor and is working on his grandfather’s letters himself. We can quote as much as we like from any of Waugh’s words across the edition. But this is a rare privilege, and it doesn’t extend to letters Waugh received. While he, like Thomas Markle, might have owned the physical paper and ink of a letter, its contents reman the copyright of whoever wrote the letter. Trust me on this: there are flow charts.

This means that we spend a lot of time talking to Waugh’s correspondents and their surviving family, tracking down who owns the rights to what and asking politely if we can publish grandma’s letters for the public good. There’s big money involved in the trade of private letters too: in December, Sotheby’s auctioned 10 letters Waugh wrote to his friend Richard Plunket Greene and his family with a guide price of £15,000 – £20,000. Some auction houses are kind, and let our editors take notes from such collections before they disappear, perhaps forever, from the public eye. Others are less generous, leaving us to squint at the fragmented images of letters that advertise lots on auction websites.

All this could change though, if the courts accept that it’s ok to publish Markle’s private letter because

her role and lifestyle rely on publicity and because there is significant public interest in her affairs. Could those arguments also apply to writers? Waugh would be horrified. He guarded his privacy fiercely, even moving house after it was “invaded” by journalists. During a mental breakdown, he was tortured by the paranoid delusion that his friends were reading his personal letters aloud, and mocking them, on BBC radio. And he didn’t have to contend with a tenth of the publicity surrounding the Sussexes.

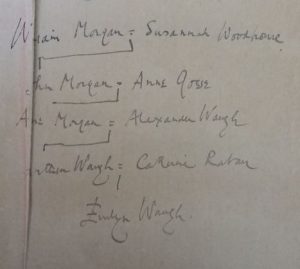

Curious, too, that the Mail claim it’s ok to publish the letter because it is not ‘an original literary work’ but a simple recounting of known facts. This biographer at least was not aware of such a difference in law. As I understood it, copyright in private letters applies equally to shopping lists and drafts of major works (though the penalty for beaching copyright might vary in each case). For Waugh and his friends, of course, the distinction may not be obvious: is a scribbled family tree, for example, merely the re-statement of existing facts or important preparatory material for his autobiography? If we can prove that love letters to Waugh, even if sent by published writers, are “factual” rather than “literary”, may we publish with impunity? We will need a new flow chart.

Is Waugh’s scribbled family tree an ‘artwork’ or a ‘statement of existing facts’? Courtesy Evelyn Waugh Archive.

Practically speaking, a ruling in favour of the Mail would work for or against projects like ours. The misfortune of private letter collectors, whose lovingly (or cynically) acquired caches would plunge in value overnight, could be our gain. Auction houses might as well be libraries, if the contents of letters like Markle’s can be used and published by anyone, however they please. Bonham’s can open up a reading room and make money by selling coffee to academics (they’ll need a new revenue stream, after all). The only problem is – who would bother to buy our editions, born of years of careful research, if the juiciest bits (strictly non-literary of course) were freely available? And those auction houses and collectors may, in the end, guard their collections even more closely, if the only thing stopping us from publishing their contents is our inability to get close to the words on the page in the first place. That would be a huge loss to scholarship.

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Subscribe to Barbara Cooke's posts

Recent Comments