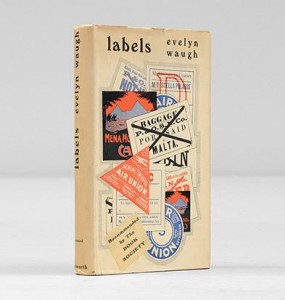

Labels: A Mediterranean Journal

Mr Evelyn Waugh, the author of “Decline and Fall,” is indiscreet, impudent, and amusing in Labels (Duckworth, 8s. 6d.), his account of a Mediterranean Cruise.

He chastises several hotels, all trains, some ships, at least one volcano, to say nothing of Paris and Naples, for their shortcomings. But his vivid pictures of scenes and people convey some of the pleasure he derived from them. Thousands of tourists go every year to the places he visited, but the eyes with which he saw them were more observant than most.

Daily Mail, 26 September 1930.

Last week saw the book group discussing Waugh’s travel book, Labels, published in 1930 and based on his trip across Europe, the Middle East and Northern Africa in 1929. The group were generally pleased to return to the more satirical tone of Waugh’s early work, nowhere more obvious than his description of Etna, alluded to in the review above:

‘I do not think I shall ever forget the sight of Etna at sunset; the mountain almost invisible in a blur of pastel grey, glowing on the top and then repeating its shape, as though reflected, in a wisp of grey smoke, with the whole horizon behind radiant with pink light, fading gently into a grey pastel sky. Nothing I have ever seen in Art or Nature was quite so revolting.’

(Labels, Penguin 1985, p. 139)

He also described the Sphinx in derogatory terms in a letter he wrote to Harold Acton in April 1929, whilst still abroad. ‘The Sphinx is a complete fraud – a shameless lump of masonry’.

(Letters, Phoenix 2009, p. 42)

However, Labels is far from a traditional travelogue. In fact, Waugh’s skewing of the actual events of his journey, paired with long sequences aboard the Stella Polaris led us to make comparisons with another peculiar journey, as depicted in The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957). We wondered if boats are particularly unsettling for Waugh? They are, after all, a kind of unfixed and transitory accommodation, not the ideal location for a writer who, as he aged, became increasingly intolerant of any kind of chaos, be it in his personal life, or in art and literature.

The “untruth” at the heart of Labels is related to an unsettling incident in Waugh’s personal life, and his relationship with his first wife, Evelyn Waugh (née Gardner, often “She-Evelyn”). They embarked on this Mediterranean trip together, but Labels has a different story. Indeed, Waugh presents himself so thoroughly as a lone traveller that the American edition of the book was entitled A Bachelor Abroad. In doing so, Waugh rewrites She-Evelyn as the wife, called Juliet, of another passenger on the Stella Polaris, Geoffrey, who we can presume to be fictional. This throws a peculiar light on the conversations Waugh subsequently has with this ‘rather sweet-looking young English couple – presumably, from the endearments of their conversation and marked solicitude for each other’s comfort, on their honeymoon, or at any rate recently married.’ (Labels, p. 24)

Waugh was recently married, about eight months prior to the trip, which began in February 1929. Incidentally, Waugh’s agent, A. D. Peters, had managed to get the pair free passage on the Stella Polaris in return for the publicity which would no doubt come about after the publication of Waugh’s book. (See Martin Stannard, The Early Years, p. 171) Juliet is very unwell during the trip and the incident in which she is lowered from the boat in a stretcher was absolutely based in reality. The same thing happened to She-Evelyn, who, suffering from double pneumonia at the time, was lowered from the boat in Port Said looking, as Waugh put it, ‘distressingly like a corpse.’ (See Selina Hastings, Evelyn Waugh: A Biography, p. 185)

Once the group knew this information we found Waugh’s attachment to the ‘sweet-looking English couple’ made a great deal more sense, and the anxiety Waugh must have felt about She-Evelyn’s rapidly deteriorating condition enables us to read his description of Naples in two ways. Waugh finds he is ‘ill at ease’ there, ‘very near to that obsession by panic and persecution mania which threatens all inexperienced travellers.’ (Labels, p. 45) Without biographical detail we can write this discomfort off as one of the disgruntled and overwhelmed tourist (a condition many of us, I am sure, can identify with!), but with it, Waugh’s description betrays the comparable panic he must have felt at the time about She-Evelyn’s health.

All the distancing techniques Waugh employs to essentially rid himself of his first wife in Labels are clearly connected with their divorce in September 1929 and work as both a snub to She-Evelyn (who left Waugh for John Heygate) and a consoling practice for Waugh himself, who was, of course, deeply hurt. However their marriage was hasty from the beginning and as Martin Stannard argues:

If the cruise had been difficult for Waugh, it had been worse for her. […] For two months she had lived almost exclusively in Waugh’s company or that of comparative strangers. He was (and remained) a demanding companion for anyone in perfect health. For an invalid, despite his assiduous attentions, it must have been a testing time. Some of the romantic enthusiasm which had led her into an impetuous marriage had inevitably died during that trip. During the year of their marriage she had suffered two serious illnesses and an operation. In order to collect material for his travel diary Waugh had often disappeared on solitary excursions. Now she wanted company.

(Stannard, p. 179)

Waugh made one final attempt at distancing himself from the events depicted in Labels, evident in 110 very special first editions of the book. Not only did the author sign these copies, but they also included a page of the original, hand-written, manuscript. This was apparently somewhat of a brief fashion in publishing around this time, but it seems an appropriate action in the case of Labels, a book which so carefully disguises and scatters references to its source material.

Subscribe to Rebecca Moore's posts

Subscribe to Rebecca Moore's posts

I have now finished Labels – hurrah! I enjoyed it, though having had the information about Geoffrey and Juliet’s true identities early on meant that I was, thereafter, constantly reading between the lines. I noted only one possible reference to ‘She-Evelyn’ later in the book (after G and J’s departure) – Waugh mentions a woman in his company had a gold lighter or cigarette case stolen from her while in a club. Could it be that she was only mentioned there because it supported his narrative – that wherever they happened to be (Algeria? Port Said?) was potentially dangerous for travellers? I’m probably reading too much into it and maybe ‘dangerous’ isn’t quite the right word – unsophisticated, inauthentic?

Re, the Sphinx – didn’t a female character in one of the earlier books mention the Sphinx in less than complimentary terms – the ‘how sad’ postcard?

Sorry it has taken me a month to reply! I am glad that knowing about Geoffrey and Juliet allowed you to read between the lines! It does make it hard to believe anything he wrote in that book really …

You are quite right about the Sphinx – you are thinking of his short story (if you can call it that!) ‘Cruise: Letters from a Young Lady of Leisure’.