Dr. Leigh N. Fletcher introduces a special issue of Phil. Trans. A that summarises the international effort to launch ambitious new missions to the distant Ice Giants, Uranus and Neptune, following a Royal Society Discussion Meeting in January 2020 that was led by University of Leicester Planetary Scientists.

Uranus and Neptune sit alone on the “Frozen Frontier”, the only major class of planet not to have had a dedicated robotic explorer. Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft in history to offer any sort of glimpse of these worlds, and a rather fleeting one at that, as the intrepid spacecraft flew by Uranus (January 1986) and Neptune (August 1989) on its way out of our Solar System. Voyager was never intended to visit the Ice Giants, and its myriad discoveries used technology designed in the 1960s and launched in the 1970s. Unlike the larger hydrogen-rich Gas Giants (Jupiter and Saturn), which have been comprehensively explored by the Galileo, Juno, and Cassini spacecraft, neither Ice Giant has ever had an orbital mission, and even if we were to somehow launch tomorrow, more than half a century will have elapsed between the Voyager encounters and the next missions to explore an Ice Giant. But today, at the start of the 2020s, there is renewed excitement that a mission to Uranus or Neptune might finally be within our reach.

This sense of anticipation was felt by the 200+ participants who gathered at the Royal Society in London in January 2020, entering the Wellcome Trust lecture theatre past a display containing Herschel’s hand-written notes on the discovery of Uranus, a mere 239 years (around eight human generations) earlier. This was the largest international gathering of Ice Giant scientists, engineers, mission planners, policymakers, and industry to date. Over three days of the conference (the meeting was extended to host splinter meetings at the Royal Astronomical Society and Geological Society), the participants revealed the scientific potential of new missions to explore the Ice Giants (their origins, interiors, atmospheres, and magnetospheres) and their rich planetary systems (their satellites, both natural and captured, and their rings). This culminated in a series of papers collected in a Special Issue of Phil. Trans. A. Proposed for the 30th anniversary of Voyager’s encounter with Neptune (1989), this Discussion Meeting and Special Issue serve to reinforce the growing momentum for an ambitious, paradigm-shifting mission to the Ice Giants as the next logical step in our exploration of the Solar System.

Why Uranus and Neptune?

Amidst the bewildering complexity observed in the growing census of extrasolar planets beyond our own Solar System, one discovery has raised Ice Giant science to new levels of importance – it is neither the enormous gas-giants like Jupiter, nor the small rocky worlds like Earth, that dominate the census. Instead, worlds only slightly smaller than Uranus and Neptune (the “sub-Neptunes” and “super-Earths”) appear to be the most common outcome of the planetary formation process. Uranus and Neptune might just be our closest and best examples of a class of planets that dominates our galaxy, holding the missing pieces of the planetary formation puzzle.

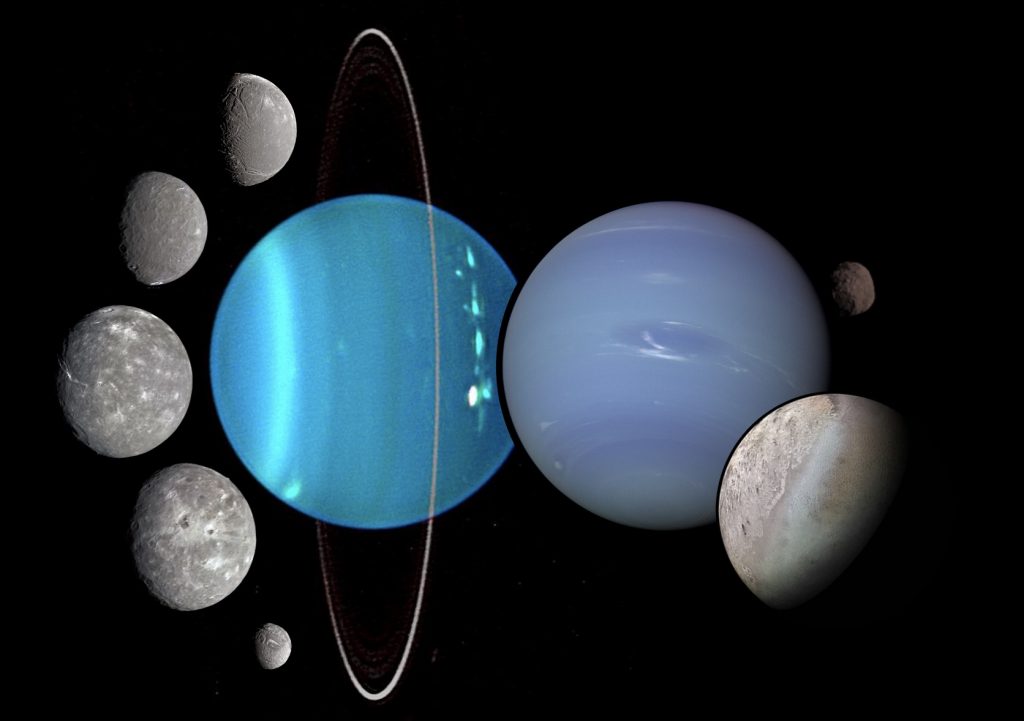

Furthermore, these two worlds can be considered as two endmembers of this class of planets, the products of divergent evolution from shared origins. Uranus has an extreme axial tilt of 98o, subjecting its atmosphere and magnetosphere to unique interactions with sunlight and solar wind, whereas Neptune has a more “Earth-like” seasonal tilt of 28o. Uranus has a collection of icy “classical” satellites that might represent a primordial Ice Giant system, whereas the Neptune system is dominated by an interloper – enormous Triton captured from the Kuiper Belt, an accessible world that represents both Dwarf Planets (like Pluto) and potentially Ocean Worlds (like Europa and Enceladus, with subsurface oceans beneath thick icy crusts). Uranus has a sluggish atmosphere with episodic outbursts of convective storms, whereas Neptune’s meteorology is so vigorous that the appearance of the world can change from one day to the next. Many of these differences could be explained by gargantuan collisions in their early history, with Uranus subjected to an impact so large that it completely altered the planet’s evolution. A comparison of both worlds may teach us about the environmental conditions and formational processes at work across our galaxy.

Onwards to the Ice Giants

For these reasons and more, scientists have been dreaming, planning, and preparing for a dedicated mission to an Ice Giant for several decades. Right now, two large-scale surveys of strategic priorities are underway: the Voyage 2035-2050 project to develop a plan for the European Space Agency (ESA) to succeed the Cosmic Vision programme (which includes the launch of ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, JUICE, in 2022); and the US planetary science decadal survey 2023-2032 to define scientific priorities for NASA’s planetary missions. The last US planetary science decadal survey (2013-2022) listed a Uranus mission as its third highest priority for a flagship-class mission, after concepts that ultimately became the Mars Perseverance (2020) rover and Europa Clipper mission, both of which are now well under way. The January 2020 Discussion Meeting provided an excellent opportunity to discuss advocacy for Ice Giant missions as part of these prioritisation exercises.

We should not, however, understate the challenges involved in mounting an Ice Giant mission. Most mission concepts rely on flying past Jupiter to get a gravitational kick, propelling a spacecraft onwards to Uranus or Neptune. But there’s a catch – Jupiter has to be in the right place in the Solar System for this to work, and this only occurs every 13-14 years. Optimal launch opportunities to Uranus exist in the early 2030s, but the window for Neptune is narrower and closer (2029-30). Add on the 8-12-year flight time (depending on launch vehicle and trajectory), and the orbiter would likely not arrive until the 2040s, when Uranus will be approaching northern autumn equinox (2050), and Neptune approaching northern spring equinox (2046). If we miss Jupiter slingshots in the 2030s, then we either need to invest in heavy-lift launch vehicles to get orbiters there without gravity assists, or we must wait for Jupiter to complete another lap around the Sun. But wait too long, and the northern hemispheres of Uranus’ satellites – which have never been seen by human or robotic eyes, as Voyager flew by during southern summer – will disappear once again into the shroud of winter darkness. There really is no time to lose.

An international partnership, continuing the legacy of the Cassini-Huygens mission, has formed over the past decade and is ready to take advantage of the next jovian gravity assist in the early 2030s. Before we can even arrive at that hurdle, we have a lot of work to do in persuading our space agencies (both national and international, in the case of European nations) to support an Ice Giant mission. That remains a considerable funding challenge, given the ongoing commitments to missions both existing and on the schedule between now and the mid-2030s. The potential for scientific discovery is clear, strong, and compelling, encompassing the entirety of planetary science, and reaching across disciplines to heliophysics and astrophysics. However, as explained in our Phil. Trans. special issue, science is a necessary, but not necessarily sufficient, condition to mount such an ambitious endeavour. We hope that national and international space agencies will rise to the challenge, enabling a mission to the Frozen Frontier that will shape planetary exploration for the generations to come.

Further Reading:

- Join the conversation: Twitter @IcyGiants

- Report on the Royal Society Ice Giant Systems Discussion Meeting: https://ice-giants.github.io/

- Fletcher et al. (2020), Ice Giant Systems: The Scientific Potential of Orbital Missions to Uranus and Neptune, Planetary and Space Science, Volume 191, 105030 (https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.02963)

- Fletcher (2020), Onwards to the Ice Giants, Astronomy & Geophysics, Volume 61, Issue 5, 1 October 2020, Pages 5.22–5.27, https://doi.org/10.1093/astrogeo/ataa071

- Hofstadter et al. (2019), Uranus and Neptune missions: A study in advance of the next Planetary Science Decadal Survey, Plan. Space Science, Volume 177, 104680 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2019.06.004).

- Special Issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A on Future Exploration of Ice Giant Systems (http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/378/2187)

- Space Science Reviews Topical Collection: In Situ Exploration of the Ice Giants

Subscribe to Physics & Astronomy's posts

Subscribe to Physics & Astronomy's posts

Recent Comments