To mark UK Disability History Month, which falls between 16th November and 16th December, Archives and Special Collections are showcasing items from our holdings which shed light on these often hidden histories.

/

Our collections span a wide time period and their content can contain language and terminology reflecting contemporary attitudes that today may be considered outdated, offensive or harmful. In order that they may provide a basis for critical learning and research, and so that we can create a more inclusive environment for the future, we do not remove, censor, or restrict access to these items. The collections help chart changing attitudes to disability and improvements to inclusivity over the last two centuries.

/

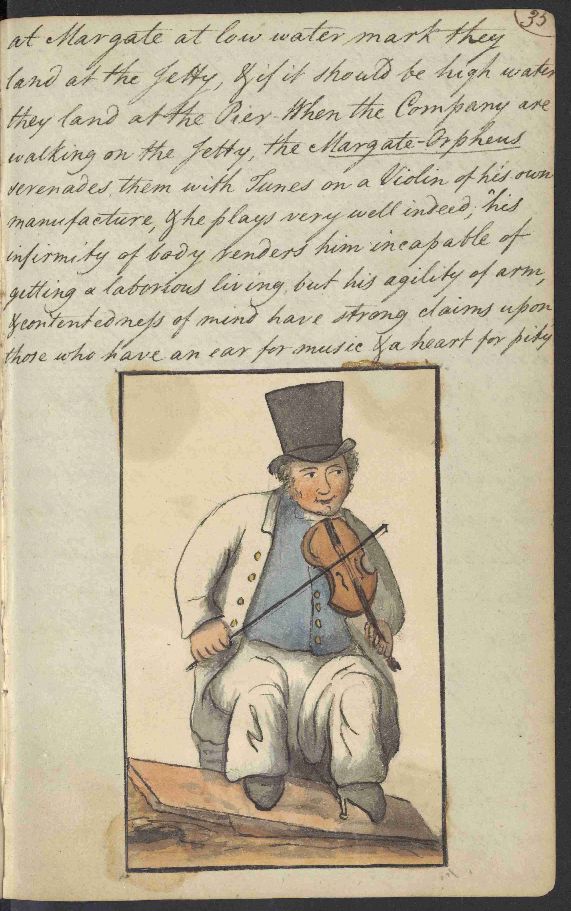

William Fry was a nineteenth-century travel writer. Archives and Special Collections holds his handwritten Excursions to Canterbury and Margate 1826, which includes mention of a disabled fiddler on the pier at Margate, accompanied by a coloured sketch. The nature of the fiddler’s disability is not clear, and his name is not given: he is described only as ‘the Margate Orpheus,’ with Fry writing: ‘His infirmity of body renders him incapable of getting a laborious living, but his agility of arm and contentedness of mind have strong claims upon those who have an ear for music and a heart for pity.’

/

Various forms of sign language have been used by Deaf communities for centuries. In 1576 Thomas Tyllse, ‘naturally deaf and dumb,’ married Ursula Russell at St Martin’s Church (now Leicester Cathedral). Their marriage certificate records how Thomas ‘for the expression of his mind instead of words, of his own accord used… signs.’[i] This is the first recorded use of sign language in Britain.

/

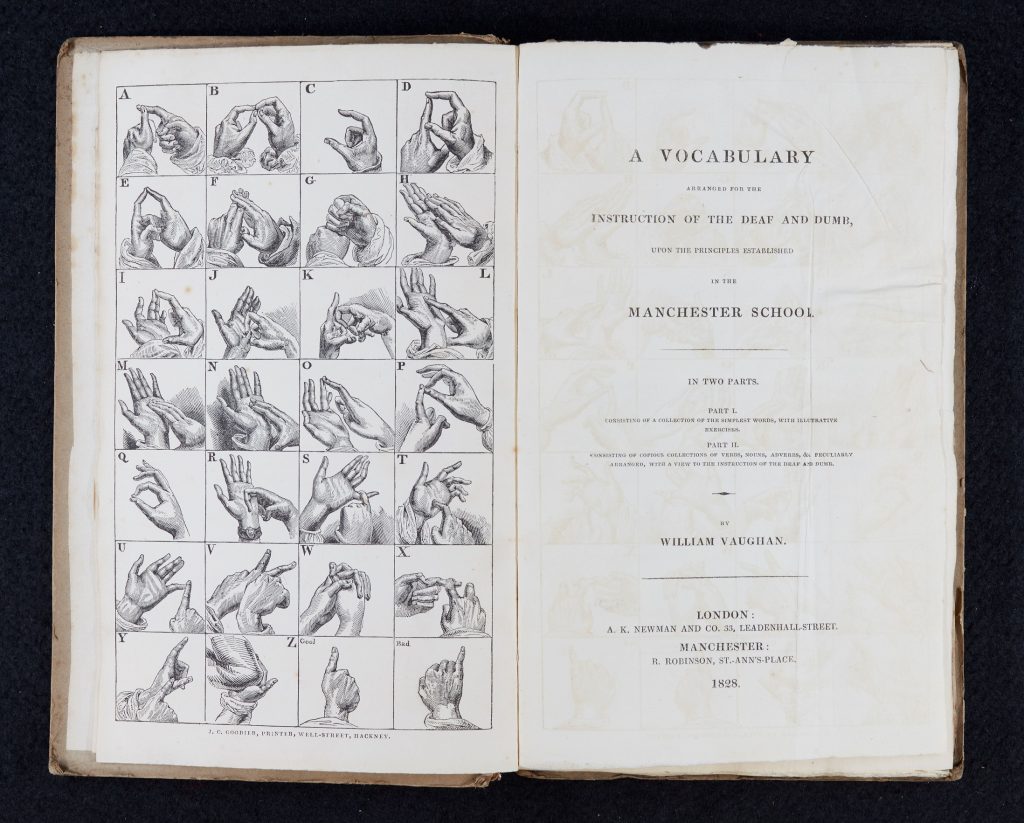

Dating from 1828, the frontispiece to William Vaughan’s A Vocabulary Arranged for The Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb includes illustrations of what would become the British Sign Language (BSL) alphabet.

/

/

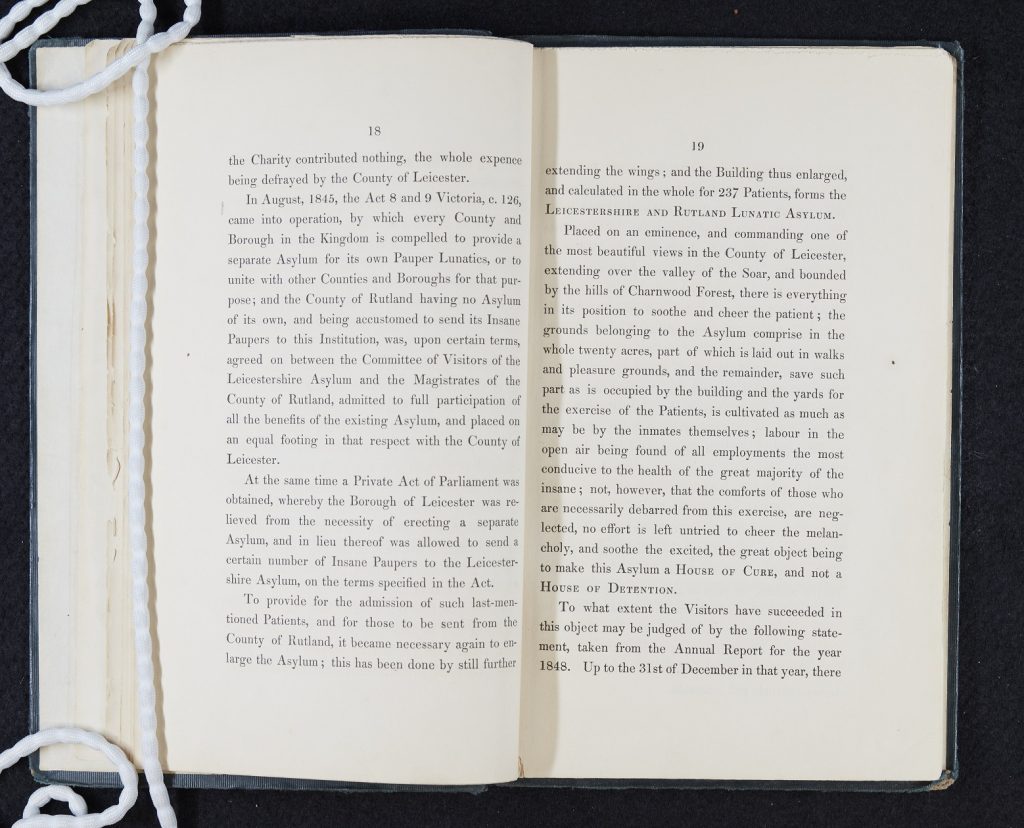

What is today known as the Fielding Johnson Building, now the university’s centre of administration, began life as the Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic Asylum, lunatic being an all-encompassing term used at the time for many mentally and physically debilitating illnesses. Purpose-built, the asylum was opened in 1837. It is perhaps worth noting that the word asylum derives from the Greek word for safety or refuge. In popular perception, Victorian asylums have a notorious reputation. However, they were also the forerunners of modern mental health hospitals. In Leicester’s case, the Rules for the General Management of the Institution make clear that ‘the great object…[is] to make this Asylum a HOUSE OF CURE, and not a HOUSE OF DETENTION.’[ii]

/

/

To find out more about the history of the Fielding Johnson Building, explore the Heritage Hub’s Fielding Johnson Building Trail (hard copies available from the Attenborough Arts Centre or the Library Information Desk). In 1908 the asylum moved to new premises in Narborough, and the original building stood empty until the First World War, when it was repurposed as the 5th Northern Field General Hospital. More than 95,000 wounded servicemen were cared for between 1914 and 1919.

/

//

The Leicester Guild of the Crippled was founded in 1898, and is now known as the disability charity Mosaic 1898. Mosaic ‘work[s] to provide life-enhancing services, care and opportunities for disabled people (and all those supporting them), promoting inclusion, equality, independence, choice, empowerment, respect and dignity for all.’[iii] The East Midlands Oral History Archive collection EMOHA/40: Mosaic Our Lives contains 87 interviews with people living with disabilities in Leicester.

/

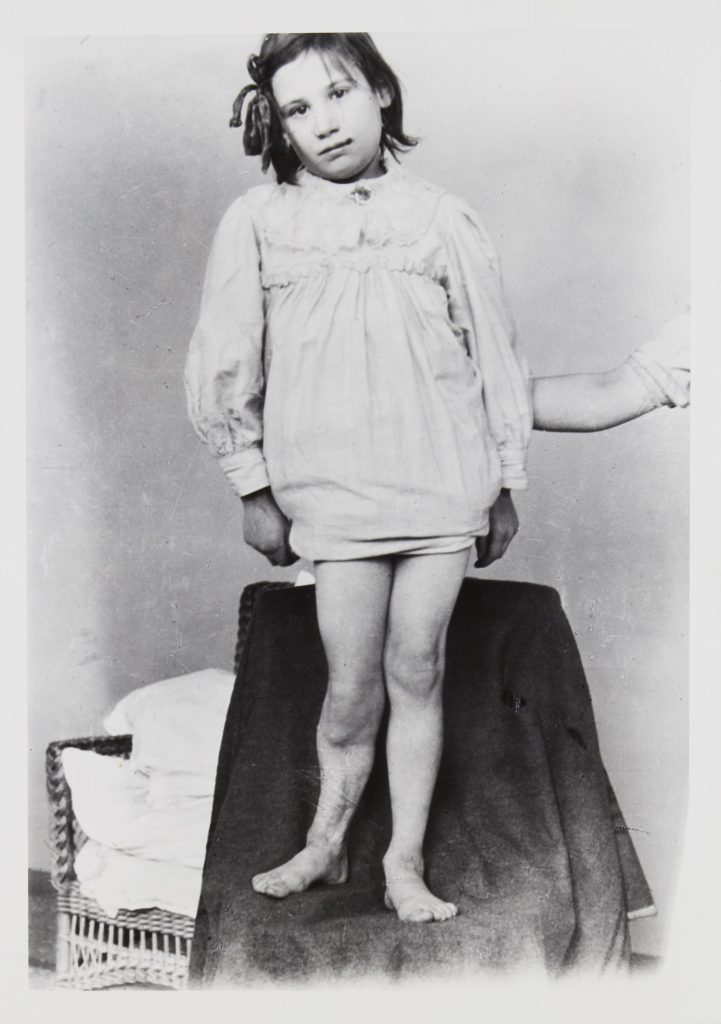

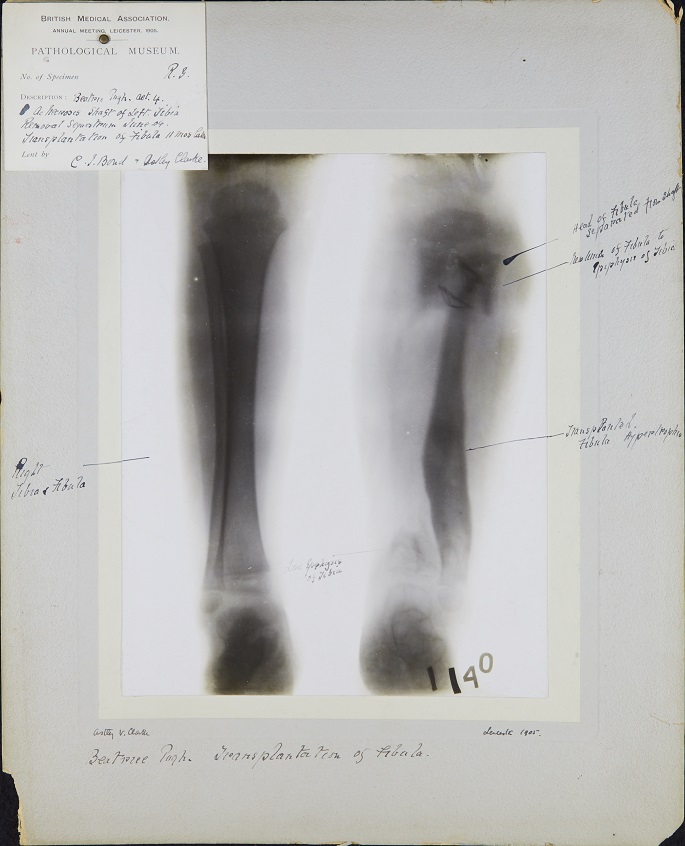

This year’s theme for Disability Month is Children and Young People. Among the historical records of the Leicester Medical Society is this photograph of a young girl, Beatrice Pugh, who underwent a transplantation of her fibula (one of the bones in the lower leg) in 1905. Beatrice had osteomyelitis (inflammation of the bone marrow). The x-ray and its handwritten notes demonstrate the operation, which was carried out in two stages.

line break here

//

The fundraising appeal for what is today known as the Attenborough Arts Centre (formerly the Richard Attenborough Centre for Disability and the Arts) was launched on 22nd June 1990, hailed as ‘a major arts centre for the disabled.’[iv] Its first patron was Lord Richard Attenborough and the building was opened by Diana, Princess of Wales; both were prominent campaigners for the rights and dignity of disabled people. Today the AAC exists for everyone, ‘aim[ing] to be a sector leader for inclusion and a centre of excellence for disability arts.’[v] One of the Centre’s Honorary Patrons is percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie, who has been profoundly deaf since the age of 12.

One of Archive and Special Collections’ most popular holdings is the archive of Sue Townsend, Leicester-born author and playwright most widely known for her best-selling novel The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, aged 13 ¾ (1982). Throughout her life, Townsend experienced various periods of illness, including eventually losing her sight due to diabetic retinopathy. These experiences informed her writing. In press interviews, Townsend describes how her ill health inspired Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years (2009), which sees Adrian in remission from prostate cancer, and which draws on her own experience of living with illness.

/

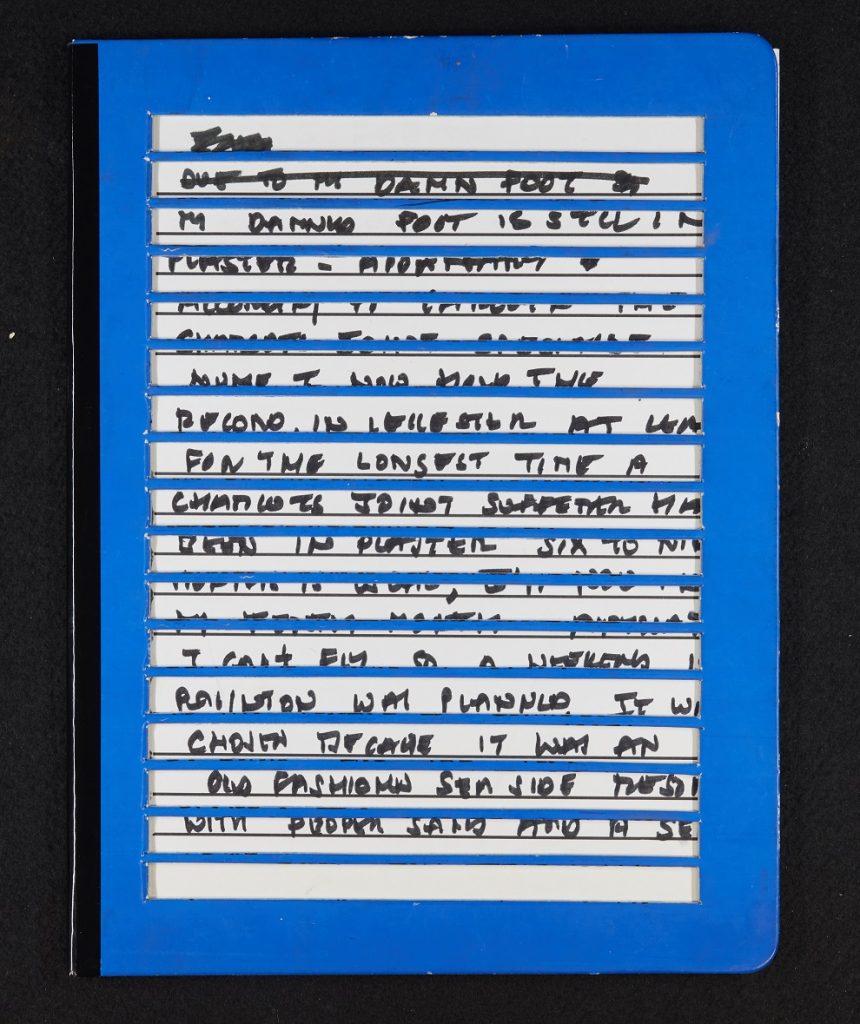

Shown here is a simple aid used by Townsend to help guide her handwriting.

/

The University’s AccessAbility Centre, based in the David Wilson Library, supports students who have learning difficulties, chronic physical or mental health conditions, or a disability. It has also produced material such as this booklet on dyslexia for the guidance of lecturers, markers and tutors, enabling them to more effectively support students’ academic development.

/

The University’s commitment to disability inclusivity remains ongoing. In 2023, in association with the National Trust and the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, the University of Leicester produced Everywhere & Nowhere: Guidance for Ethically Researching and Interpreting Disability Histories.

/

To find out more about how the Library is working towards becoming a more welcome and inclusive environment, please see the inclusive collection policy. For further resources, explore the Disability Month reading list. This includes books suggested by students as part of the Represent scheme, a Library campaign to diversify collections.

[i] ‘Marriage Certificate of Thomas Tillsye,’ UCL: History of British Sign Language, accessed November 9 2023, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/british-sign-language-history/beginnings/marriage-certificate-thomas-tillsye.

[ii] Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic Asylum: Rules for the Management of the Institution With Prefatory Remarks by the Committee of Visitors (Leicester: J.S. Crossley, 1949),SCM 10693, p.19.

[iii] Mosaic 1898, accessed November 9 2023, https://www.mosaic1898.co.uk.

[iv] Quoted in Leicester Mercury, June 22 1990; cutting filed in ULA/PCB35.

[v] ‘About us,’ Attenborough Arts Centre, accessed November 8 2023, https://attenborougharts.com/about-us.

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts