Please note that this post contains content relating to suicide and the Holocaust. If you are affected by this topic, please be aware of our available support information for students and support services in the community.

Saturday 27th January is both the International Day in Remembrance of Victims of the Holocaust and the UK’s national Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD). This date is the anniversary of the 1945 liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp by the Soviet Union. In 2024, the theme of UKHMD is ‘the fragility of freedom.’

/

Rudolf and Hans Majut were brothers, two of the millions caught up in the Nazi persecution of Jews and non-Aryans prior to and during World War II. Archives and Special Collections holds their personal papers, manuscripts and family photographs, catalogued as MS 201, and Rudolf’s collection of around 6,000 books is held on the library’s open shelves. Because the books and papers are primarily in German, the Majut Collection has, to date, received little attention.

/

Rudolf Majut was born in 1887 and Hans in 1892, in Vienna, Austria. In around 1897 they moved with their parents, Wilhelm and Anna, to Poland and then to Germany, where they settled in Berlin. The family was of Jewish origin, but in 1914 Rudolf was received into the Protestant church; his baptism certificate survives among the papers.

Few other papers survive from around this time and the family’s history during the First World War is unclear. However, Hans’ 1933 short story Die Flucht [The Flight, or The Exodus] refers to the shadow it cast over many lives: ‘Wie in die meisten Lebenslaeufe unsere Tage hatte der Grosse Krieg auch in dein meinen eine Kerbe geschlagen’ [as in most lives these days, the Great War has left a mark on mine].

/

Rudolf had obtained his doctorate in 1912 and became a Studienrat, ‘a post equivalent to a teacher in a secondary school but with the status of a civil servant.’[i] The focus of his academic research was German Literature, specifically Georg Buechner. Hans became a dentist, but outside of this was clearly a prolific writer. Both brothers had a strong creative streak and the collection contains many manuscripts of their early writings, mostly poems, Märchen [fairy tales] and short stories.

/

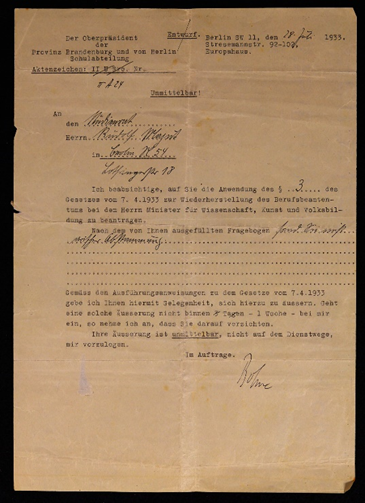

In 1933, after Hitler and the National Socialist party came to power, the Law for Restoration of the Civil Service was passed, which debarred non-Aryans from holding office. Rudolf was granted a temporary reprieve due to having served since 1914. However, persecution of Jews continued to intensify. In 1935 Rudolf was excluded from the Reichsschrifttumskammer, or RSK [Reich Chamber of Culture], which meant he could no longer publish his academic research. In 1937, driven to despair by the intensifying persecution, Hans killed himself. Almost twenty years earlier, in 1920, he had written a short story entitled Der Selbstmord [The Suicide].

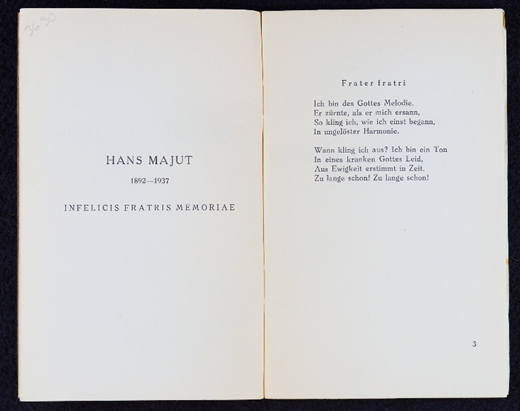

Rudolf’s book of poetry Der Werdekreis, published in Berlin later that year, is dedicated to Hans. The frontispiece reads infelicis fratris memoriae [to the memory of an unhappy brother] and the first poem, in which the speaker laments ‘Ich bin ein Ton/In eines kranken Gottes Leid’ [I am a note/in a sick god’s song], is titled ‘Frater fratri’ [from brother to brother].

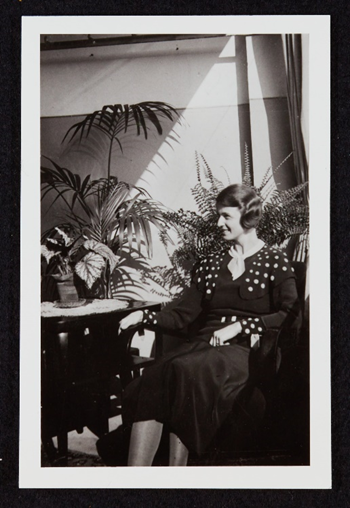

At the time of Hans’ death, unable to teach or publish his research in Germany, Rudolf was studying evangelical theology in Basel, Switzerland. Dozens of letters from this period survive, sent between Rudolf and Käthe Genetet; years, later, in 1995, a selection was published as Briefe fuer Kaethe 1933 – 37: Eine Auswahl [Letters for Käthe 1933 – 37: A Selection]. Käthe was a teacher and mathematician from Berlin, where she was acutely aware of the dangers posed to Rudolf – and others of Jewish heritage – by the Nazis. It was she who ‘warned [Rudolf] of the personal dangers posed by the Nazi regime in Germany.’[ii] Käthe herself also risked the ire of the Nazis, as ‘[i]t was impossible to get any post in the realm of the Education department without producing the membership-card of the Nazi party and its number.’[iii] As she wrote starkly many years later, she ‘had not this card nor intended to get one.’[iv] Käthe left Germany in 1938, slipping over the Swiss border ‘without giving notice or leaving any trace,’[v] and joined Rudolf in Basel.

In May 1939 Rudolf and Käthe arrived in England, refugees from Hitler’s persecution. They fled their homeland with the help of Dr George Bell, Bishop of Chichester, who operated a support network for Evangelical ministers of Jewish descent. On the 7th June 1939, they ‘married and were safe.’[vi] Safe, perhaps, but not trusted: after the outbreak of war Rudolf was briefly interned as an ‘enemy alien’ at a camp in Hutyon; he then worked as pastor at another camp on the Isle of Man. In 1941 the Majuts were able to come to Leicester, where Rudolf taught German in a local secondary school. He then lectured at Vaughan College, then at Loughborough College, and finally at the University of Leicester, where he spent the rest of his career and was made an Honorary Professor after his retirement in 1970.

/

Rudolf and Käthe gained naturalised British citizenship in 1947. Käthe – known to the English as Kate, the anglicised form of her name – was granted it as Rudolf’s wife rather than in her own right. They remained in Leicester for the rest of their lives, but never forgot their German Heimat [homeland]. Rudolf continued to write; themes of exile and homelessness, wandering and foreignness, resonate throughout both his academic work and his poetry. Käthe too wrote, although not as prolifically, in a similar vein, and after her husband’s death became involved with the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies, founded in 1995.

/

Reimchronik 1930 – 1950, a selection of Rudolf’s verses published posthumously by Käthe, details their Wanderjahren [years of wandering]. Arranged in eight sections, it charts Rudolf’s journeys from Germany to Switzerland, Switzerland to England; the chaos of the war years and the strangeness of the Alien’s Internment Camps; and finally the finding of a home of sorts in Leicester.

/

Initially rejected by Germany, Rudolf was later honoured by his former country. In 1957 he was awarded the Bundesverdienstkreuz 1. Klasse [Cross of Merit First Class].

/

Rudolf Majut died in 1981, leaving his papers and books to the university. Käthe lived until 2005, dying at the age of one hundred.

Dass ich heim nimmer geh,

Muss ich mir tragen.

Dass ich dich nimmer seh

Frei wie du warst,

Als du mich eingebarst,

Macht mich verzagen.

/

From ‘Heimat’, in Reimchronik 1930 – 1950 (Köln: Schertgens & Co., 1983). Loosely translated: That I will never return home/Is a burden I must carry./That I will never see you again/Free as you were/When you gave birth to me/Makes me despair.

[i] ‘Rudolf Majut Papers,’ Institute of Languages, Cultures and Societies, accessed December 1, 2023, https://ilcs.sas.ac.uk/library/germanic-archives/rudolf-majut-papers.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Käthe Majut, brief biographical notes, included in correspondence to Herbert Penn (1991), Majut Collection: University of Leicester Archives and Special Collections, MS 201/ Correspondence/Box 4.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts

[…] Bloomfield, Library Advisor (Archives and Special Collections): My favourite is probably the Majut Collection, but since I covered this in an earlier post I will choose the ‘Woman at War’ section of the […]

Hello Eleanor – during some recent research on the history of Birkenhead, I noticed that a Rudolf Majut lived in Alton Road, Oxton, on the Wirral in 1940, however Oxton isn’t mentioned in your article – do you think that Rudolf spent time up here in Oxton?

Many thanks,

Jemima Gore

Hello Jemima, thankyou for your comment. Yes, this must be the same Rudolf Majut. I have checked on Ancestry and found a register from 1939 showing Rudolf and Käthe Majut living at 9 Alton Road. Rudolf spent some time working on an internment camp on the Isle of Man, which isn’t far from the Wirral. They came to Leicester in 1941.

Glad you found this post – do you have any connection with Rudolf Majut or Käthe?