Please note that this post contains content relating the Holocaust. If you are affected by this topic, please be aware of our available support information for students and support services in the community.

/

One of my current projects is translating the letters held in the Bejach archive, in order to improve accessibility for researchers who lack the language skills to read them in the original German. The letters provide a fascinating and poignant glimpse into the wartime lives of Jewish refugees. Descriptions of mundane everyday events such as going to the cinema co-exist alongside intense concern for family members known to have been deported by the Nazis.

/

The archive contains around 25 – 30 letters in German, about a third of which have been translated to date. The vast majority are from Hans Bejach to his nieces Irene and Helga-Maria. The girls fled Nazi Germany, aged thirteen and eleven, on one of the last Kindertransports, leaving behind their father Curt (Hans’ brother) and older sister Jutta. Arriving in Leicester in August 1939, they were unofficially adopted by the Attenborough family and lived with them on what is now the university campus. Although it was intended that they should go on to America, wartime conditions and the slow process of getting visas resulted in long delays, and the girls remained in England for seven years.

/

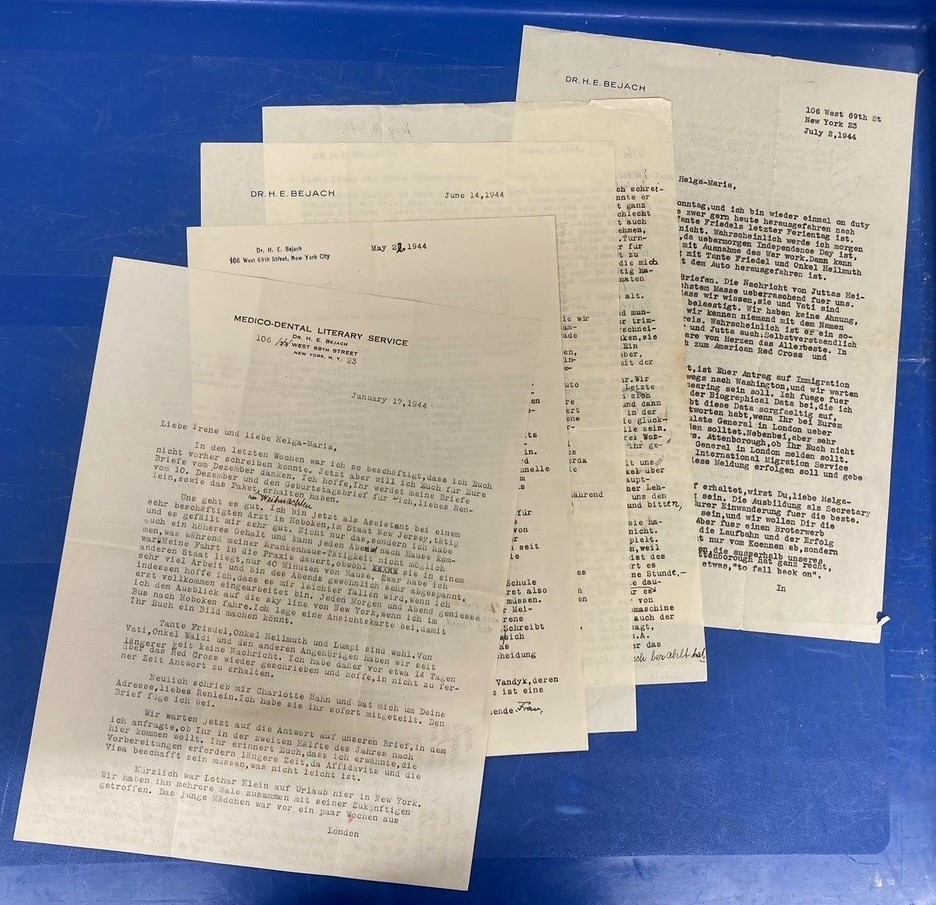

Most of the letters date from 1940 – 1945. Hans Bejach and his wife Friedel had emigrated to America before the outbreak of war, settling in New York. He was a doctor, and had to retake his medical examinations in order to gain his American practising certificate; the earlier letters describe the long hours of study he had to put in. Although he complains of being intensely busy, even more so after he passed his exams and started working in a doctor’s practice, he wrote regularly to Irene and Helga. Friedel worked long hours as a seamstress and was apparently not as prolific a correspondent as her husband, although her handwritten postscripts – brief messages of affection or advance notice of parcels she had sent containing food or clothes – often follow Hans’ typed, longer letters.

/

Only Hans’ side of the correspondence survives. He often complains – sometimes gently chiding, sometimes outright berating – that he and Friedel do not hear often enough from the girls. He asks them to write regularly, and also to keep up their German; both girls, thanks to English schooling, became quickly Anglicised. Hans comes across as rather fussy and overbearing, but his concern for the girls, and for other family members left behind in Germany, is clear and unwavering, and incredibly moving.

/

Anxious to secure the girls’ future, Hans applied for immigration visas on their behalf, and from 1943 the letters are filled with references to the necessary paperwork, affidavits, medical examinations, Consular Generals both in Washington and London, and the inevitable bureaucratic delays. He also encouraged both girls to take up secretarial training. Helga wanted to become a ballet dancer, but this ambition seems to have been quashed by both her uncle and her host parents; Hans echoes Mrs Attenborough’s concerns that it would be an uncertain, unreliable career, and that she needs an alternative ‘to fall back on,’ at least ‘until you marry.’

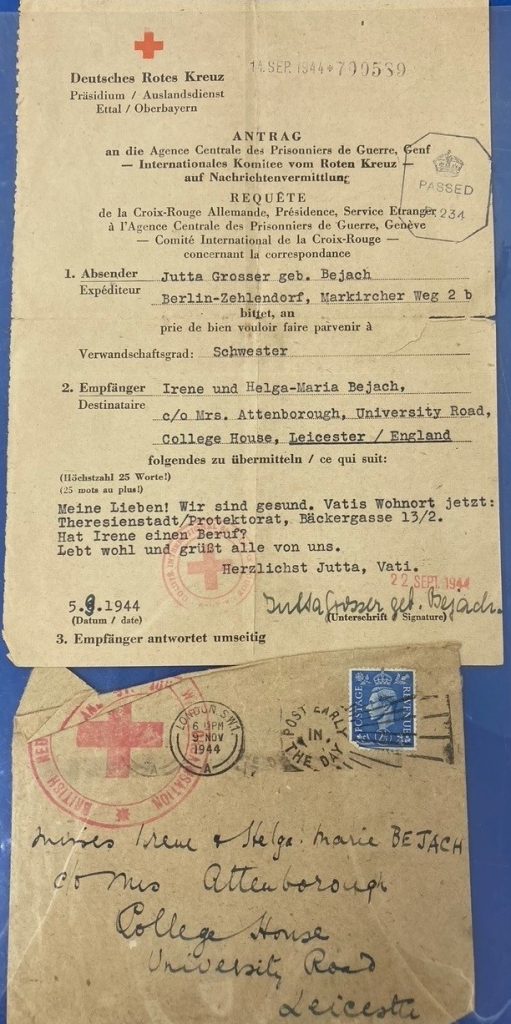

Little details in the letters provide snapshots of life in wartime: the rationing, the air-raid siren testing, the unreliable postal service, going to the pictures (Hans was very excited by the girls’ connection to the morale-boosting film In Which They Serve, which featured Richard Attenborough in his first film appearance). But across all the letters lies the shadow of fear, an unvoiced, ever-present concern for the fate of Jutta and Curt. In 1944 Jutta married, apparently suddenly and unexpectedly, and rather to Hans’ slightly disapproving surprise. She and her husband survived the war and eventually emigrated to New York, where presumably they were reunited with Irene and Helga-Maria, Hans and Friedel, as well as other members of the family who had also emigrated.

/

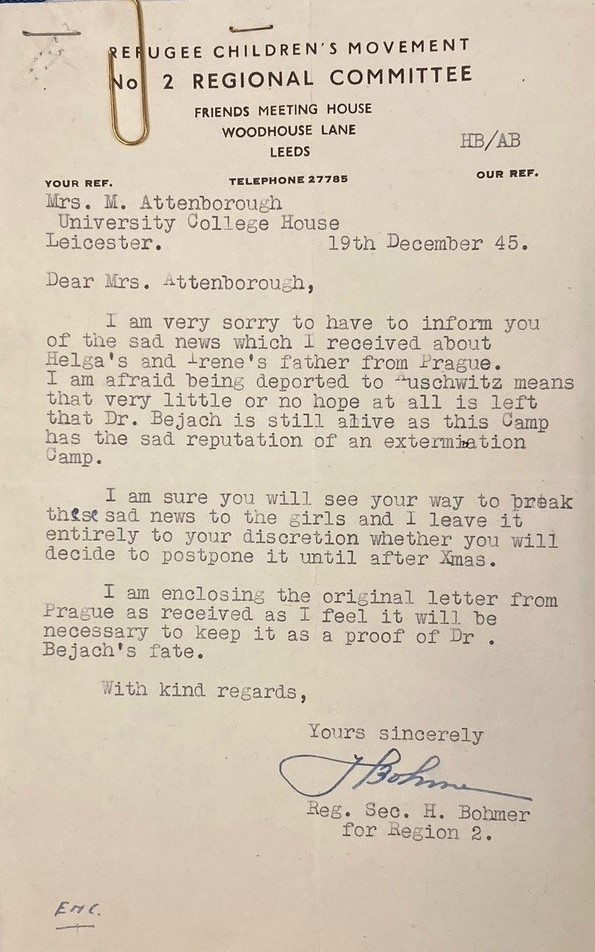

However, Curt Bejach – or ‘Vati’ (the German diminutive for ‘daddy’ or ‘papa’) as the letters name him – did not survive the war. The saddest letter in the Bejach collection is not in German, is not from Hans, and is not to the girls. It is in English to Mary Attenborough, from an H. Bohmer, secretary of the Refugee Children’s Movement. Dated 19th December 1945, it explains that ‘very little or no hope at all is left that Dr. Bejach is still alive as this Camp [Auschwitz] has the sad reputation of an extermination Camp.’

/

After this date no more letters from Hans to the girls survive. Grief is eloquent in its silence.

/

The Bejach archive is searchable online through our archive catalogue.

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts

Subscribe to Eleanor Bloomfield's posts