16 November to 16 December 2022 is UK Disability History Month, an annual event creating a platform to focus on the history of the rights and dignity of disabled people. Over the next few weeks, we will be highlighting some aspects of our collections relating to the history of disability. Some of the collection items we will be discussing contain historical language that would today be considered offensive. English Heritage have produced a glossary of terms used within disability history, including many that appear frequently in historical records.

At the heart of the University of Leicester campus is a large rectangular building known since the 1960s as the Fielding Johnson Building. Opened in 1837 as Leicestershire County Lunatic Asylum, the building gave the first public provision of care for pauper ‘lunatics’ (an all-encompassing term used at the time for many mentally and physically debilitating illnesses). It was originally large enough to house 104 patients, by the time it closed 71 years later it had expanded significantly to increase capacity. A brief history of what was known from 1845 as Leicestershire and Rutland County Asylum, can be found on the main University website. This post is the second in a series that will draw attention to items in Archives and Special Collections that shed light on the history of disability.

Leicestershire & Rutland Lunatic Asylum: Rules for the General Management of the Institution (Leicester, 1849) [SCM 10693]

This slim volume was bequeathed to the Library of University College Leicester by James Johnson in the late 1920s. It opens with a Preface outlining the legal frameworks as they related to mental illness from the 14th century onwards, before going on to describe the institution itself. Much emphasis is placed on the location of the asylum and its perceived benefits to its inhabitants:

Placed on an eminence, and commanding one of the most beautiful views in the County of Leicester, extending over the valley of the Soar, and bounded by the hills of Charnwood Forest, there is everything in its position to soothe and cheer the patient; the grounds belonging to the Asylum comprise in the whole twenty acres, part of which is laid out in walks and pleasure grounds, and the remainder, save such part as is occupied by the building and the yards for the exercise of the Patients, is cultivated as much as may be by the inmates themselves…

Leicestershire & Rutland Lunatic Asylum: Rules for the General Management of the Institution (Leicester, 1849) [SCM 10693], p. 19

The author goes on to underline the progressive aims of the institution, that was intended as ‘a HOUSE OF CURE, and not a HOUSE OF DENTENTION’.

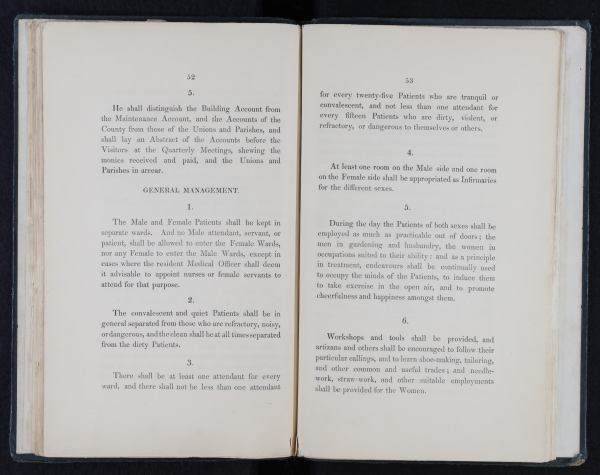

Under a section titled ‘General Management’ we can gain some insight into the daily lives of those who were committed to the asylum in the early Victorian period (p. 42-57). Men and women were kept in separate wards, and the ‘convalescent and quiet Patients shall be in general separated from those who are refractory, noisy, or dangerous, and clean shall be at all times separated from the dirty Patients’. There should be at least one attendant for every ward, with a higher staff to patient ratio for those ‘who are dirty, violent or refractory, or dangerous to themselves or others’. During the day, the patients should spend as much time as possible outdoors; the men in ‘gardening and husbandry’ and the women in ‘occupations suited to their ability’. Workshops and tools were provided to enable people to carry on with the usual occupations or to learn a trade such as shoe-making or tailoring for men, and needlework or straw-work for women. Arrangements were made for a library of books and cheap publications of ‘a cheerful nature’ to provide amusement and entertainment, in addition to Bibles and prayer books. Staff were expected to treat patients ‘kindly and indulgently, and never to strike or speak harshly to them’, and no patients should be ‘restrained or secluded at any time except by Medical authority’. Friends and family were allowed to visit once a fortnight.

Other sections of the book describe the roles of medical and housekeeping staff, organisational and administrative arrangements, and the supply of food and other provisions to the asylum. While this small volume tells us very little about the lived experiences of those who were committed to the asylum, it does challenge some preconceptions about how people experiencing mental ill health were treated in Victorian England. It was also intended to challenge the ideas and attitudes of contemporaries who read it. At the time of publication, an article appeared in the Leicester Journal, which can be accessed via British Library Newspapers on Gale Primary Sources (University login required). Under the headline, ‘The Lunatic Asylum’ the article begins:

There is no building in our town which, until lately, so much attracted the notice of the traveller, as that on Knighton Hill; and, doubtless, many a sigh has been heaved, when, in answer to enquiries, he has learnt that the huge edifice was a Lunatic Asylum; a sign, in some instances, at this fresh reminder of human ill; but in many, from a mis-conception of the nature of the place altogether; an idea that it was but in truth a Prison….

Leicester Journal, 5 Oct. 1849, p. 3.

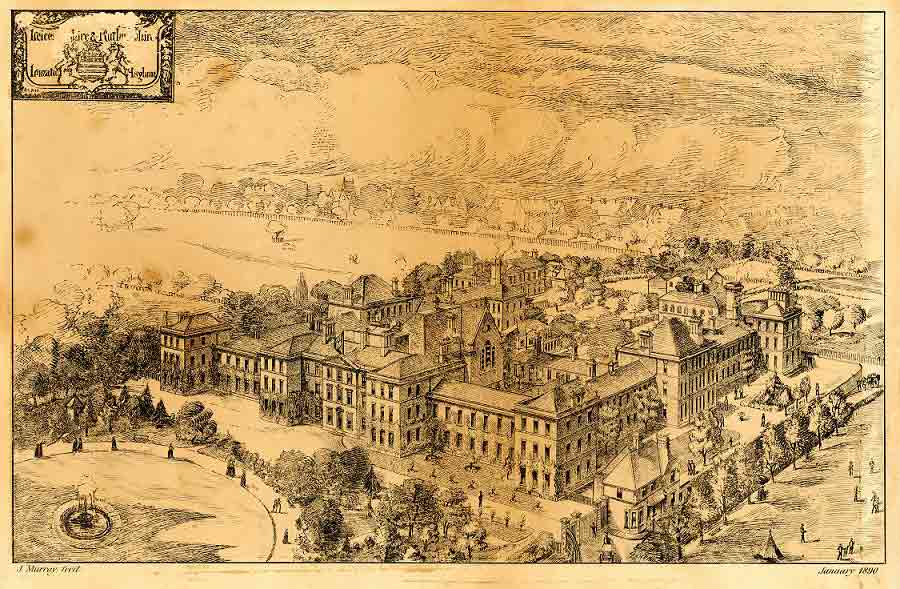

The anonymous journalist concludes that few readers would dispute the claim that the asylum is ‘a House of Cure, and not a House of DETENTION’. This conclusion is echoed by local historian Diane Lockley, who has written the most detailed account to date of the institution (Diane Lockley, The House of Cure (2011)). Lockley draws on the detailed records of the asylum held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, including a long series of patient case books. These detailed records are the main archival source for researching the history of the asylum. There is one other original item in our own collections – an engraved print by James Murray, a draughtsman who had at one time been treated at the asylum. The print gives a birds eye view of the building and adjoining grounds towards the end of the 19th century. The building has undergone many changes since the foundation of the University in 1921, including the demolition of the section located where the David Wilson Library now stands. It is, however, still recognisable and should be remembered as a site inexorably linked to changing approaches to mental healthcare during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

A digitised copy of the Rules for the General Management of the asylum can be accessed via the Wellcome Collection.

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Subscribe to Simon Dixon's posts

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.