Following the hugely successful ‘Return to Waugh‘ event that was hosted by the British Council Milan, in collaboration with the University of Milan on 17th November, Milena Borden reflects on the relationship Waugh had with his Italian translator, Valentino Bompiani and considers the sociopolitical context of the Italian society that welcomed Waugh’s post – war work in particular.

As I was going to the Return to Waugh seminar in Milan last month, walking on the elegant via Alessandro Manzoni towards the distinguished building of the British Council, I was reflecting on what did it actually mean to have Evelyn Waugh’s novels published in Italian language and for the Italian public in post-war Italy. I was thinking that there probably was a difference between admiring Waugh’s exceptional prose in its Italian translation and connecting it with the actual country and culture.

The Italian publisher of Waugh was Valentino Bompiani (1898 – 1992). Born in Rome, he was a count, connected intellectual, editor, playwright and a publicist. In his memoirs Via private (1974) and Dialoghi a distanza (1986) Bompiani writes a lot about the value of literature, theatre celebrities and the Italian intellectuals of his time. Brideshead Revisited was the first Waugh book published by Bompiani in 1948. Judging from the correspondence with Waugh, their relationship was a business one. They met only once in Rome and although there is no record in the Waugh’s Diaries about it, the meeting seems to have happened when he was in Italy in April 1950.

Return to Waugh event, British Council, Milan, 17th November 2018. Photo by Marco Canani British Council, Milan.

Bompiani had many reasons to publish Waugh. Firstly, he wanted to promote English literature on the domestic market, which was then dominated by American bestsellers and also because of its potential for filming. From a literary point of view, Bompiani was interested in a classical English prose to balance the post-war influence of modernist writers with James Joyce and Virginia Woolf being most among Italian anglophiles. However he was a sharp and connected businessman who did not take sides in late 1940s and 1950s Italian debates about modernism versus traditionalism. Bompiani became well known for his publication of Alberto Moravia and Elio Vittorini, both representing an Italian modernism and neo-realism whose ambitions were quite different from Waugh’s.

Another key Waugh promoter was Emilio Cecchi (1884-1966), the “Accademico d’Italia” of post-war Italy. An expert of Anglo-Saxon literature, and a most conservative critic and journalist, Cecchi was also a lecturer and traveller. He reviewed Waugh favorably in the Italian press before he was published in Italian, which was a significant step in his consequent promotion.

But what about the most obvious connection between Waugh and Italy – his, and Italy’s, Catholicism? Was not religion the first and foremost reason for translating Waugh? Italy, Catholicism, the Pope (whom Waugh personally met in 1945 at the Vatican) and Italian culture and literature have been interconnected at least since the time of Dante Alighieri. After the war, Italy was badly damaged and very poor. But although the Holy See was struggling to dissociate itself from the crimes of the Mussolini’s regime, popular Catholicism was on the rise. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s it energized its grass roots welfare organizations and Democrazia christiana (Democratic Christians), one of the two main political parties, ruled until 1992. Italian writers have always cared a lot for religion, even when against it. Waugh’s Catholicism must have found a natural place in a country which adores literary language, loves to discuss its religion and is addicted to politics.

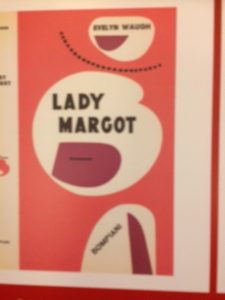

On the other hand, Bompiani’s choice of the Milan artist-designer Bruno Munari (1907-1998) to design the dust jackets for Corpi vili (Vile Bodies), Lady Margot (Decline and Fall), Spada e onore (Sword of Honour) and Misfatto negro (Black Mischief) speaks for the publisher’s ambition to move with the times. Munari was associated with futurism and the ‘art of the concrete’ and his style added a modern touch to Italian translations of Waugh. One wonders, though, if Waugh liked the fragmented and modernistic illustrations of his book covers.

Behind all that can be said about Waugh in Italy, hangs intriguingly the shadow of his most Italian book, Waugh in Abyssinia (1936). There is plenty in it about Italy and politics. It is a travelogue revealing what Waugh thought of the colonial and fascist Italian rule in Ethiopia. But maybe Bompiani and his readers would have preferred to miss it. I am convinced, though, that somewhere in this black hole would be yet another discovery of Waugh in Italy.

Read a more detailed reflection of the Return to Waugh event by Milena Borden.

Subscribe to gboland's posts

Subscribe to gboland's posts

Recent Comments