The following guest post is kindly supplied by Andrew W. Mellon fellow Dr Naomi Milthorpe.

The following guest post is kindly supplied by Andrew W. Mellon fellow Dr Naomi Milthorpe.

In my first Waugh and Words post I raised some questions about what the collections at different research archives can reveal for Waugh scholars and enthusiasts. I’m interested in how each collection illuminates a different aspect of Waugh; why Waugh is such a fascinating figure for the archivist; and whether Waugh consciously worked to construct his own archival legacy. One way we can continue to answer these questions is by thinking about Waugh’s manuscript corpus, whether at the Harry Ransom Center at Texas, the Brotherton Library at Leeds, or here at the Huntington in California. The Huntington’s collection offers a couple of entry points to thinking about Waugh’s construction of his legacy, in the manuscript of Ninety-Two Days, and in the correspondence series between Waugh and his publishers, Chapman & Hall.

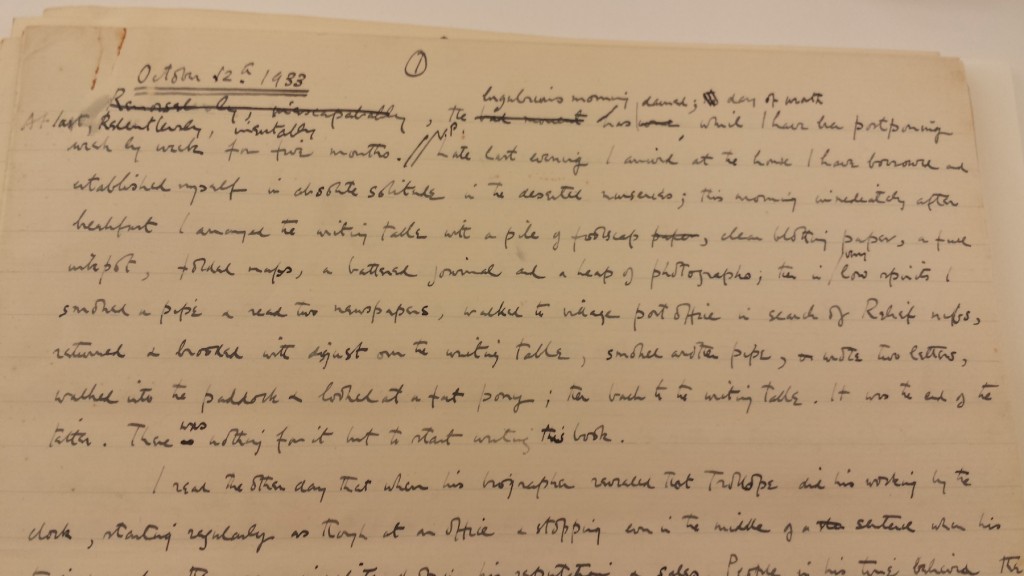

The manuscript copy of Ninety-Two Days is one of the jewels of the Huntington’s Collection: a full autograph copy with Waugh’s corrections. In many respects it is physically reminiscent of the manuscripts in the Harry Ransom Center, written in ink on loose foolscap sheets, with insertions pasted in or written on the verso sides. Waugh put off for “five months” the “day of wrath” (Box 2.6.1, 1) – that is, writing the book – and then dashed it out in a month, between October and November 1933, while staying at a house in Bognor, Sussex owned by Diana and Duff Cooper (Stannard 344).

Ninety-Two Days isn’t as textually interesting as some other of Waugh’s manuscripts – unlike the surprise beheading of Captain Grimes that exists in the HRC’s autograph manuscript of Decline and Fall and is reproduced in the Huntington’s corrected typescript (Box 1.3.2). Nor is Ninety-Two Days Waugh’s best travel book (what’s your favourite? I’m partial to Labels). Both of these facts might be due to its hasty composition over only a month, under difficult personal and professional circumstances (Stannard 334-356). However with closer attention it may yield insights to scholars working on the travel writing: for instance, reading the manuscript one is reminded of Waugh’s boredom, his obsession with the horrors of native food, and the insistent presence of animals and insects in the narrative. Waugh obviously wished to emphasise insect life in particular. The long disquisition on cabouri, betes rouges, and ticks at the beginning of Chapter 4 (“Insects played a fairly prominent part in my experience throughout all this period”), is a later insertion, made on the verso side of page 1 of the manuscript chapter.

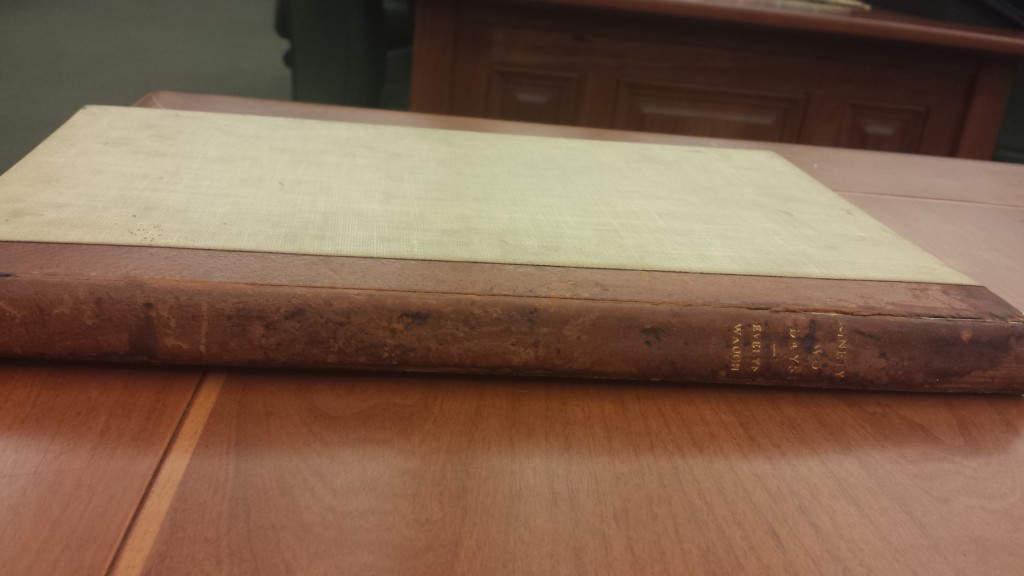

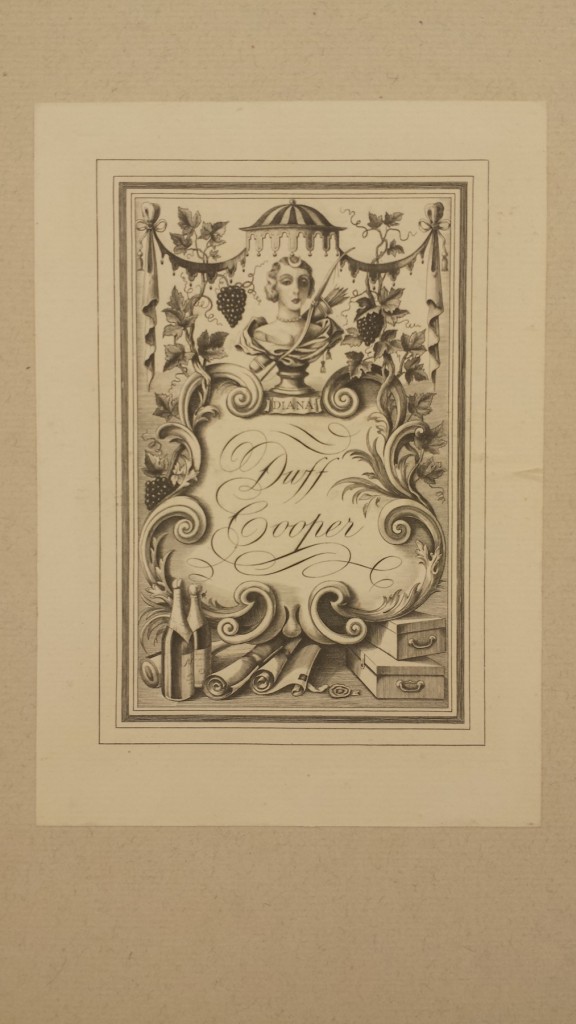

What interests me is the way this and other manuscripts were gathered or dispersed by Waugh through gifts and exchange. As we know of Vile Bodies (first given to the Guinness family, until recently in private hands, and now housed at the Brotherton), Waugh sometimes gave his manuscripts away. In the case of Ninety-Two Days, the manuscript was given to the Coopers, perhaps as thanks for the use of their Bognor house while writing. The manuscript arrived at the Huntington in a marbled slipcase, stamped with Duff Cooper’s bookplate featuring a fetching bust of Diana Cooper surrounded by grapes and bottles. The Duff Cooper bookplate may not automatically suggest ownership by Duff, though: several of the Huntington’s association copies inscribed to Diana also bear Duff’s plate, suggesting that perhaps the plate was added later. The Huntington collection’s cataloguer, Gayle Richardson, told me that the manuscript was found in a cupboard in the Cooper house and sold to Loren Rothschild, to become part of his gift to the library.

While Ninety-Two Days is a recent addition to the public manuscript archive, there is evidence that Waugh did think about the future of his manuscript works. The correspondence with Chapman & Hall shows Waugh looking to reassemble dispersed works in autograph and typescript for something only referred to as his “box.” In October 1963, Gillon Aitken, then a junior editor and Waugh’s main correspondent on production and copyright matters, wrote to Waugh about a copy – perhaps the corrected proof – of Brideshead Revisited, offering it for inclusion in the box. (Box 4.78) In December of the same year, Chapman & Hall were moving offices. Aitken writes again with another find: “While clearing out a cupboard apparently full of rubbish, I came across the typescripts of BRIDESHEAD REVISITED, MEN AT ARMS, LOVE AMONG THE RUINS and WORK SUSPENDED. Imagining that you would like these for your box, I send them to you with this letter. I am sorry they are in such poor condition.” (Box 4.82) I like the metaphoric gulf between the cupboard “apparently full of rubbish” and the treasure trove of manuscript materials found there.

His publishers were keenly aware of the value of Waugh for posterity – and for their accounts ledgers. A c.1966 memorandum circulated by Associated Book Publishers Ltd (the parent company of Chapman & Hall) notes the importance of keeping Waugh titles in print following his death, “since if we do not the lose the rights. […] Waugh, as one of the greatest English writers of the last thirty years, may have a long life. We know from our experience with authors like Arnold Bennett and Conrad that once they are regarded as classics schools start to set them and over the years we sell a substantial number of copies” (Box 9.3.15).

Other evidence supports the idea that Waugh was conscious of the need to create an archive in preparation for his entry into the literary canon. For instance, his plan in October 1944 to transform Midsomer Norton into a “secret house” for his books and bric-a-brac that would eventually become a “public museum and memorial to myself” (Letters 190). Such traces suggest Waugh’s early awareness of his status in twentieth century letters. There is physical evidence, too. The manuscripts housed at the Harry Ransom Center are exquisite, and highly durable, objects – fully bound, gilt stamped on the spine, and marked with the Waugh bookplate. The fact that Waugh kept and cared for his manuscripts in this way suggests that he understood their value as objects of future interest. While Waugh never in fact built himself a museum, the idea of a memorial showcasing his life and work exists in the several libraries which house his manuscript archives.

The literary manuscripts, correspondence and ephemera at the Huntington can show us many things about Waugh, including his writing process, shifting interests and values, and his friendships and associations. In my next post I’ll look at the Huntington’s collection of Waugh association copies – those books an author inscribed as gifts to friends and colleagues – to see what they tell us about Waugh and his circle.

Image credits

Autograph draft p.1 detail: Box 2(6.1), Evelyn Waugh Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Image by author.

Flapcase and bookplate: Box 9(13), Evelyn Waugh Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Image by author.

Naomi Milthorpe is Lecturer in English at the University of Tasmania and a 2015-16 Andrew W. Mellon Short-Term Fellow at the Huntington Library. For more information about the Evelyn Waugh Papers at the Huntington Library, you may consult the Finding Aid.

Subscribe to 's posts

Subscribe to 's posts

[…] can read more about the Huntington’s Evelyn Waugh collection in Evelyn Waugh, Cynic? and Manuscripts as Memorials by Naomi […]