by Dr Rebecca Acres, Honorary Fellow, University of Leicester

Whether or not it ever actually happens, Brexit is the defining political and leadership challenge of our times.

As I write this the Prime Minister of our supposedly sovereign tiny island nation, our “Perfidious Albion” if you will, is presenting to the EU 27 a (hopefully) impassioned plea to extend the Article 50 process in order to avoid us accidentally committing an act of national economic suicide and leaving the EU with no deal.

It also so happens to be the day upon which I am considering Irwin Turbitt’s article “Crisis? What Crisis?” in my leadership coursework.

Turbitt’s 2012 article looks at how we use language to achieve consensus around major negative events and what needs to be done about them. He references George W Bush in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 who called the attacks a crisis and assumed a Command and Control ‘leadership’ style as a consequence. In previous units we have considered Mayor of New York Rudy Guiliani who did much the same and whose paternalistic style in the immediate aftermath of the attacks was well received by New Yorkers. However, Turbitt then points out where George W started effectively engineering the ongoing situation linguistically to support the Command and Control style that he preferred.

The phrase “War on Terror” begins to appear and wars need generals for people to look to for instructions.

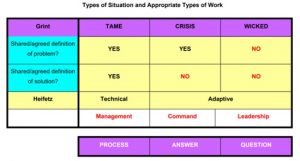

However, Turbitt ultimate conclusion is that actually this is a sign of poor and inflexible leadership and doesn’t extricate the maximum positive from the negative event. He uses the work of Keith Grint and Ron Heifetz to produce the following heuristic:

Tame situations have an agreed process of either solving the issue or identifying the solution.

In “A Good Crisis – and how not to waste it” Turbitt refers to this as “Research and Development”; by contrast Wicked situations are referred to as requiring “Trial and Error”. The broad problems need to be agreed upon first then, out of a certain degree of chaos and experimentation, solutions are developed (some of which will fail but we don’t know which ones at the outset). Turbitt says only wicked situations require leadership (because he asserts that command is not leadership) and that tame situations require management (used as shorthand for a more processual approach). Further, he states that the role of the leader in each situation type is to give something different to their team, either: correct processes, direct answers or questions to resolve.

Brexit is the epitome of the wicked problem.

No one agrees what the problems are (either that led to a vote to leave or the problems with the deal itself) and absolutely no one agrees on the solutions (even within individual political parties!)

However, the political party leaders in the House of Commons and particularly the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition are a case study in Turbitt’s principles of how leaders avoid and reclassify a situation towards their preferred style.

Leaders who prefer Command and Control (like George W Bush) tend to reclassify situations in favour of or perpetuate Crisis. This perfectly describes Teresa May who expresses a strong preference for command and against adaptive leadership; she is effecting this by using the “My Deal or No Deal” rhetoric and by perpetuating and re-emphasising the time pressure of Brexit.

By contrast, Jeremy Corbyn shows a strong preference against command and control. He has chosen to re-classify the situation: focussing on economic austerity as the problem which caused the leave vote and treating this as a tame issue i.e. if the people are against the economic policy of the government of the day then our process to correct the problem is a general election. The issue here is that by reclassifying the situation as tame you fail to acknowledge there may be a great deal of other problems that have not got agreed definitions or easy solutions.

The Tame approach fails in situations with high levels of complexity – or a tendency towards chaos – because it gives you tunnel-vision.

Finally, in my view this heuristic also explains why the House of Commons taking over control has not solved the issue of Brexit. According to Turbitt, the first steps in the solution to a Wicked problem are to take a wide-ranging view and to identify the adaptive challenge. Until the House of Commons (or society more widely) agrees a shared/agreed definition of the problems both with relation to and underlying Brexit they’re never going to be able to agree solutions. This work is going to be time-consuming and not necessarily orderly but I believe very necessary if we are ever to move forward from Brexit whether the act itself happens or not.

Subscribe to Nate's posts

Subscribe to Nate's posts

Recent Comments