From newspaper comic strips to children’s morning television, animated characters are universally engaging and entertaining. Political cartoons, therefore, must be one of the most accessible approaches to politics, right? The short answer is, not necessarily. The longer answer is, yes, but only with the right tools.

Appreciating the many facets of a political cartoon can be challenging. Through the piloting of our ‘Covid in Cartoons’ project, aimed at providing young people with the skills to understand and use political cartoons to engage in discussions about the pandemic, we became well-placed to recognise these potential challenges and adapt the course so that participants were provided with the tools required. Drawing on this collaborative project between the University of Leicester, Shout Out UK and Cartooning for Peace, this blog outlines a helpful framework to address these challenges in the classroom.

The Simple View of Reading

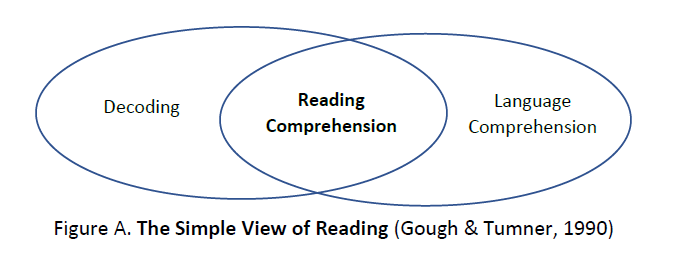

In this post, we liken the comprehension of political cartoons to the comprehension of reading. Specifically, we reference the Simple View of Reading (SVR; Gough & Tumner, 1990), a classic framework used to explain reading comprehension.

According to the SVR, reading comprehension is dependent on two skillsets: (a) decoding and (b) language comprehension. Decoding refers to the ability to convert printed symbols into language (i.e., understand that letters make sounds and sounds make words). Language comprehension refers to the ability to understand language (i.e., understand the meaning of words). Notably, the SVR suggests that reading comprehension is a product of these skills: Decoding x Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension (Figure A). Therefore, if an individual has zero decoding skills or zero language comprehension skills, they will also have zero reading comprehension (e.g., 0 x [any value] = 0)

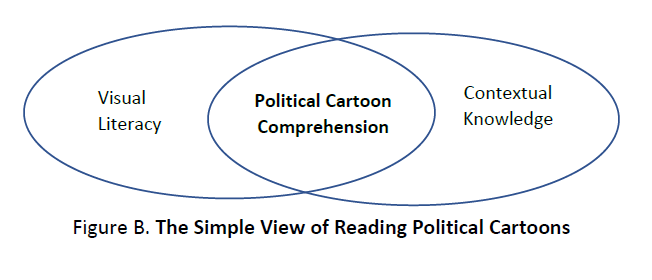

With this in mind, let us revisit political cartoons. To understand a political cartoon a reader must have an understanding of the different visual techniques used by artists, and knowledge of the context at hand; without both of these skillsets full comprehension is not possible. Therefore, we argue that political cartoon comprehension is also the product of two skill sets: (a) visual literacy and (b) contextual knowledge (Figure B).

Here, visual literacy refers to all of the visual techniques utilised by artists—such as the use of symbols, analogies, metaphors, labelling and caricature. Contextual knowledge includes any cultural references within the cartoon itself—this includes news/political events, and references to art, religion, and popular culture.

In this blog, we explain this framework by giving examples of recent political cartoons and consider the relative importance of both visual literacy and contextual knowledge.

The Simple View of Reading Political Cartoons: Cartoon Example 1

Visual Literacy

L’Andalou (Algeria) –

Cartooning for Peace

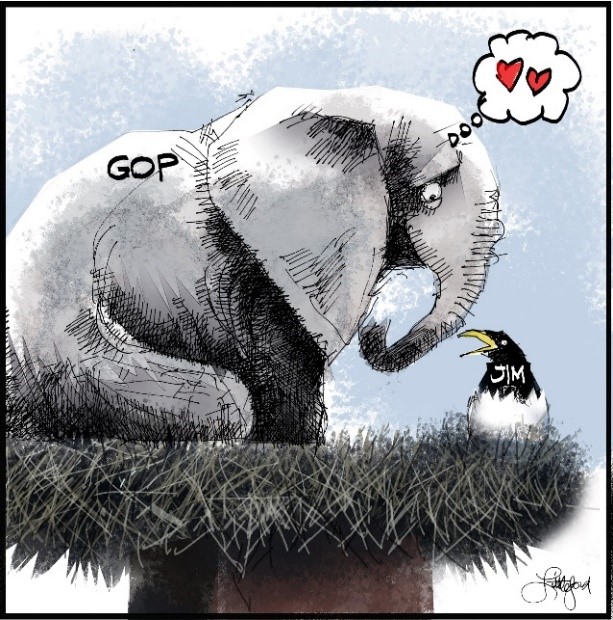

Let us start with a relatively accessible cartoon. In terms of visual tools, Cartoon Example 1, by Algerian cartoonist L’Andalou, operates by means of analogy—a literary device which involves the comparison of one situation to another. In this case, the artist uses this technique to draw the likeness between a meteor wiping out dinosaurs and the COVID-19 virus wiping out humans. The cartoonist makes this analogy as clear as possible by illustrating both situations (note that this is not always the case- see Cartoon Examples 3 and 4 with the analogy of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam in which only the metaphor is demonstrated). However, this is not the only visual technique used in the present drawing; the reader also needs to be familiar with the use of symbols. In this cartoon, the COVID-19 virus is represented by a large green particle, here likened to a meteor. To comprehend the analogy, therefore, one must also understand symbolism. Because the artist represents this virus particle as a familiar symbol it is easily decodable. [Note that symbolism in political cartoons can also be more nuanced—see Cartoon Examples 5 and 6 with an elephant representing the US Republican Party].

Contextual Knowledge

Cartoons are also context-dependent. For example, the reader of Cartoon Example 1 needs to be familiar with the historical extinction of dinosaurs; without an understanding that dinosaurs were wiped out by a meteor, the analogy to being wiped out by a virus is not accessible. The contextual knowledge of this cartoon is once again reasonably available (see Cartoon Example 6 for an example of more in-depth knowledge about the history of Jim Crow laws in the USA). Moreover, Cartoon Example 1 may not have been produced or understood a mere two years ago: the symbol of the virus has only become synonymous with COVID-19 virus within this time. Therefore, the context of the current visual meaning making of the pandemic through the symbol of the COVID-19 virus is necessary for comprehension.

The Simple View of Reading Political Cartoons: Cartoon Example 2

Visual Literacy

Tjeerd Royaards (Netherlands) — Cartooning for Peace

Now let’s look at a slightly more complex cartoon. In Cartoon Example 2, by Dutch cartoonist Tjeerd Royaards, the artist uses metaphor to covey meaning. In this case, the artist illustrates that statues are ‘rooted in racism.’ To comprehend the cartoon, the reader needs to associate two definitions of root: (a) the part of a plant that attaches it to the ground and (b) the basic cause, source, or origin of something. Furthermore, this cartoon uses the technique of labelling in order to convey meaning; the reader knows that the statue represents ‘Racism’ because the base is labelled. Therefore, an understanding of both metaphor and the use of labelling are crucial for comprehension.

Contextual Knowledge

Hand in hand with these techniques, it helps for the reader to be familiar with the phrase ‘rooted in racism.’ The use of the word ‘root’ as meaning the cause, source, or origin, has been used in the context of racism for a long time. However, a sharp increase in the use of this phrase, at least in literature, rose sharply in 1999 and again in 2018. This overlaps with the publication of this cartoon in 2020. More to the point, this also coincided with an ongoing controversy around the removal of statues of historically racist figures. Upon closer look, the cartoon also features people holding signs with text such as ‘Justice’ and ‘Black Lives Matter.’ This provides the reader with even more context as to the events being references. It also contextualises the position of a political cartoonist in critically reporting current events. Here again, this requires the reader to be knowledgeable of these events—in this case, the Black Lives Matter movement.

Antonio Rodriguez (Mexico)—

Cartooning for Peace

Cam de la Fu (Venezuela)—

Cartooning for Peace

Ed Hall (USA)—

Cartooning for Peace

Ted Littleford (USA)

Visual Literacy and Contextual Knowledge in Practice

The two examples analysed above demonstrate just how important both visual literacy and contextual knowledge are in relation to fully appreciating the message political cartoon.

However, approaches to teaching these skillsets are notably different. Cartoonists of all nationalities and generations use similar visual techniques in their work. Therefore, providing young people with an understanding of these techniques can give them the tools to access most cartoons. On the other hand, contextual knowledge is largely dependent on a variety of different factors—and can even inform Visual Literacy. For example, in Cartoon Example 7 and 8, both cartoonists use caricature to denote Boris Johnson. This visual technique (emphasizing recognisable features, specifically of famous characters in this context) also creates a shared understanding between cartoonists and readers as to how these characters are portrayed. In this case, a reader familiar with visual literacy techniques and the appropriate contextual knowledge will be able to identify Boris Johnson in political cartoons using minimal cues of an oval face and unkempt blonde hair.

Cartoonist ZACH (Philippines)—

Cartooning for Peace

ADENE (France)—

Cartooning for Peace

Finding the Balance

When first engaging young people with political cartoons, it is important to present cartoons that contain at least some familiar references—based in the current events of their generation. This is particularly the case when discussing a cartoon that may use more advanced visual literacy techniques; a balance between the familiar and unfamiliar allows for learning to take place.

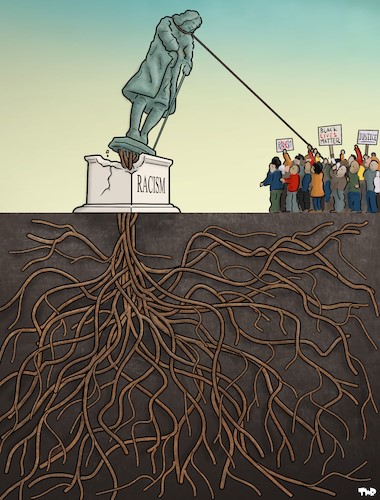

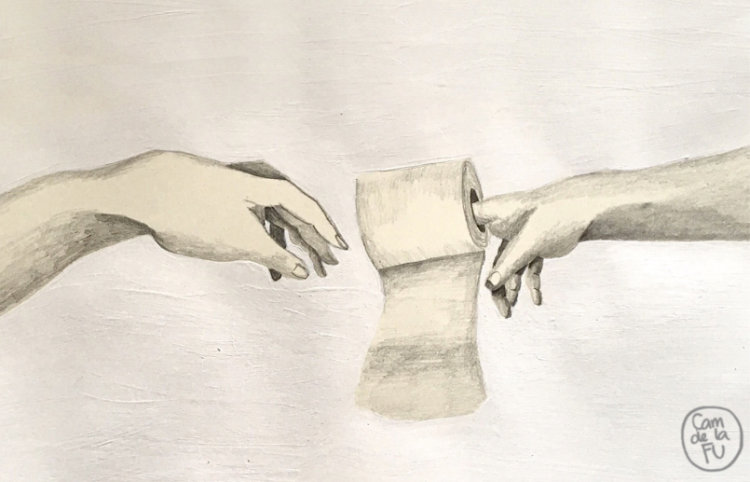

One such example from our own focus groups was that students were immediately drawn to Cartoon Example 4, by Venezuelan cartoonist Cam de la Fu, referencing the toilet paper shortage. Although students did not immediately have the Contextual Knowledge and Visual Literacy skills to recognise that this cartoon was an analogy of Michael Angelo’s Creation of Adam, they were engaged with the cartoon because it featured something from their own symbolic recall the pandemic. This interest then led to a further curiosity for learning about the original painting, and the use of artwork as an analogy.

As this example shows, once young people have an interest in developing a deeper understanding of context—and have some practice in recognising visual techniques—political cartoons become a fantastic educational tool. As we maintained at the start, cartoons are innately engaging and entertaining; students who may not initially be drawn to reading about political events have the opportunity to engage in a visual way. Furthermore, cartoons foster political conversation—encouraging readers to voice agreement or disagreement with the message portrayed. One of the aims of our project is to foster young people’s critical understanding of the world, and share their personal views around the pandemic. Through cartoons, we want to be able to support the learning of a variety of topics and inspire transferable literacy skills. With the right introduction, political cartoons have the ability to do just this.

Sarah Weidman (Research Associate) in collaboration with the Covid in Cartoons Team (University of Leicester, Cartooning for Peace, Shout Out UK)

Subscribe to fl47's posts

Subscribe to fl47's posts