By Iona Kerstin Volynets

September 05, 2025

Content warning: This article includes mentions of massacres, war, labour camps, death, and illness.

Where are you from? While for some of us, the answer is simple, for others, responding is more complicated. For two of the narrators in the East Midlands Oral History Archive’s Polish Project, the answer is more challenging than initially meets the eye.

Szeczepan Wojtak was born in the village of Cewelicze, in the Chorochow commune of the Chorochow district in Volhynia in January 1929. He was deported by the Russians to Siberia, joined the Polish army during World War II, and then moved to England by way of Karachi and Uganda (EMOHA 135/3). Julian Mamos, born in March 1932 in Volhynia, faced a similar fate. Mamos was also deported to Siberia, joined the army, and moved to England through various Asian and African nations, including Iran and Uganda (EMOHA 135/5). Both men suffered greatly in the Russian camps, experiencing and witnessing illness, death, and challenging conditions. Both Wojtak and Mamos were deported from Volhynia in 1940, after the Red Army had annexed Eastern Poland and engaged in three waves of forced deportation to “remove the most active populations from the annexed territories.” While most Polish citizens were allowed to return home after 1941, Wojtak and Mamos’ journeys brought them across the world during this time (Sciences Po).

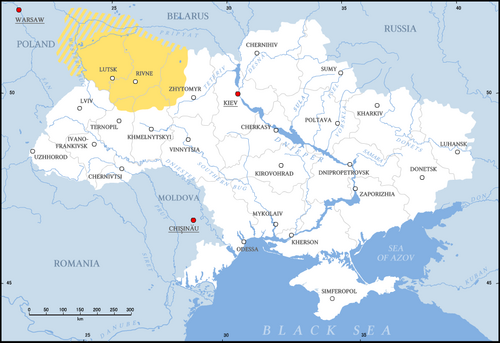

Volhynia, like much of Eastern Europe, has experienced a dance of shifting borders for the last millennia. After World War I, the region, previously part of Poland since 1793, became divided between Russia and Poland. After World War II, the region became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and after the collapse of the USSR remained part of modern-day Ukraine (Encyclopedia Britannica).

Wojtak’s birthplace of Cewelicze, known as Цевеличі (Tsevelichi) today, is now a part of the Volyn Oblast in modern-day Ukraine. Nonetheless, Wojtak, born long before 1945, describes himself as being born in Eastern Poland. Later in the interview, he says, “And when the war ended? The Poles were essentially betrayed. They sold our Poland. And our lands” and “Poles fought for freedom beyond their borders and yet remained abroad… we were… betrayed by the Allies.” Giving Volhynia to the USSR was, at the time, giving the land to the very nation that had kidnapped and deported Wojtak’s family.

Clip translation:

SW: They fought in Monte Cassino, and when the war ended, the Poles were essentially betrayed. They sold our Poland. And our lands.

KM: Do you mean the beginning of the communist era in Poland?

SW: Yes. Well, actually. Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill. At Tehran, Potsdam conference, they sold Poland, and then we got some German lands, but it was incomparable in quality and size. And so. Well, actually. The Polish army was terribly disappointed. That they fought for our freedom and yours. You have yours, but where is ours?

KM: Did your family receive any compensation for the loss?

SW: Absolutely nothing. Actually, there was much, much talk about it. They said we should apply to the… and I said, “You can’t get any water from a stone, you definitely can’t. I didn’t even think about getting any compensation. Absolutely not. “

Mamos asserts that his birthplace is Runowo, in Volhynia. The only modern-day Runowo villages are in far West Poland, which means the village where Mamos was born has likely since been re-named to a Ukrainian title, reflecting its new identity. Mamos does not directly address the transfer of Volhynia to the Ukrainian SSR. However, he describes the impact of communism in Poland after World War II, asserting that his grandmother warned them not to return to the “completely different world” that was postwar communist Poland.

Clip translation:

JM: How did the war end? People started leaving. Some went to France, who had no one. Many went to Poland because I had a father. My father, my cousin, went to Poland. My aunt. She wanted to go, because she says. My mother didn’t want her, she let her go, she says. Were you all of Russia with us? I won’t let you go.

KM: Did your mother know what the communists would bring to Poland?

JM: And my grandmother wrote, “Don’t come, because there’s nothing for you here. Because it’s a completely different world.”

The question of whether these men are Polish or Ukrainian, from Ukraine or from Poland, is no small matter. In the early 1940s, Poles and Ukrainians committed acts of ethnic cleansing against each other.

Most famously, in the early 1940s, the Ukrainian national army engaged in massacres of Poles in Volhynia, which was then occupied by Nazi Germany (Polskie Radio). The deportations of Poles and Jewish people by the Soviets and Nazis left a vacuum, where Ukrainian nationalist forces rose to power and attempted to “cleanse” the land of non-Ukrainians (Wilson Center). Experts estimate that between 40,000 and 100,000 Polish people lost their lives at the hands of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). Polish underground armies retaliated, killing between two and three thousand Ukrainians (Polskie Radio). Sources disagree on the dates of these massacres, ranging from 1942 to 1945 (Wilson Center, Polskie Radio). These events lead to continued contention between the two nations today, as Ukraine celebrates the UPA as a symbol of the fight for independence, and Poland struggles to recover victims from mass unmarked graves (Polskie Radio). Volhynia thus represents a dark tension in a crucial alliance for Ukraine and Poland.

While some relocations were initially voluntary, as populations began to refuse to leave, arrests, attacks, and murders became more prevalent. Some sources refer to this period as an ethnic cleansing of Ukrainians. Simultaneously, over a million Poles moved from Western Ukraine to Poland, many voluntarily fleeing life in the Soviet Union (Kyiv Independent). For the Soviet regime, homogenization of new territories was viewed as necessary to establish authority and legitimacy over these new regions (Lviv Center). The politics over these histories, too, remains contentious to this day.

Wojtak and Mamos were ripped from Poland in 1940. While suffering in Siberia, fighting in the army, fleeing to Uganda, Uzbekistan, and Iran, and eventually migrating to England, the land they left became the site of massacres, forced deportations, ethnic cleansings, and finally, a part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Their homeland first became part of the Ukrainian SSR and then became the site of forced deportations of hundreds of thousands of Poles, possibly including Wojtak and Mamos’ former neighbors, friends, and family.

To call these men Ukrainian would be unfair and even an unethical act of cultural erasure. Both Wojtak and Mamos gave their interviews in Polish and identify both themselves and their homelands as Poland. They are entitled to self-identification, a testimony to the resilience of their identities throughout the threats of deportation, war, and migration. Both Wojtak and Mamos articulate a sense of loss over the Poland they knew, while staunchly holding onto their Polish identity over the course of six decades in the United Kingdom.

Nonetheless, their interviews reveal Ukrainian histories buried in the archives. Any researcher seeking to understand the modern-day Volyn region of Ukraine would find their work enriched by the testimonies of Wojtak and Mamos, whose stories speak to the long history of cultural diversity and oppression in the region.

Bibliography

Campana, A. (2007) The Soviet Massive Deportations – A Chronology, Violence de masse et Résistance – Réseau de recherche, Sciences Po. Available at: SciencesPo.fr (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Encyclopaedia Britannica The church of Russia (1448–1800), in Eastern Orthodoxy. Written by John Meyendorff; fact‑checked by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, updated 11 July 2025. Available at: Britannica (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Fornusek, M. (2025) ‘Operation Vistula — the expulsion of Ukrainians from post‑war Poland’, Kyiv Independent, 4 August. Available at: KyivIndependent.com (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Center (n.d.) Genocide, Ethnic Cleansing, and Deportation: How Volhynia Became West Ukraine, 1939‑46, Wilson Centre. Available at: Wilson Center (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Lviv Center / Lviv Interactive (n.d.) The lost home: post‑war forced relocations, Center for Urban History – Lviv Interactive. Available at: LvivCenter.org (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Miller, J. (2017) ‘24 Pictures Examining Life in Communist Poland’, History Collection, 30 July. Available at: HistoryCollection.com (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Polskie Radio (2025) ‘WWII Volhynia tragedy and its lasting impact on Polish-Ukrainian relations: analysis’, Polskie Radio, English section, 31 January. Available at: PolskieRadio.pl (Accessed: 27 August 2025).

Subscribe to Colin Hyde's posts

Subscribe to Colin Hyde's posts