December 4th-6th 2019: the Arch-I-Scan project’s first encounter with proper pottery! After two weeks of planning our approach, seven of us (Penelope Allison, Evgeny Mirkes, Santos Núñez Jareño, Victoria Szafara, Alessandra Pegurri, Gabriel Florea and your faithful reporter) brave the winter morning cold to travel down to London to take photographs of whole vessels of Roman pottery in the collection of the Museum of London.

Counter-intuitive as it may be; yes, you can spend two weeks thinking about how you are going to use a smartphone to take photos of pots… From which angles are we going to take the photos? Do we rotate the pot, or do we move around it ourselves? How are we going to ensure a uniformly coloured background? How do we make sure that we have a useable scale in every picture, so that we can judge the size of the vessel? Then there were the questions of securing the materials required to execute our plans. As it turns out, two weeks can be a surprisingly short period of time to get all such things sorted.

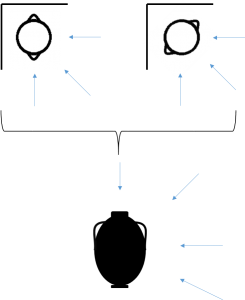

Original plan for photographing whole vessels

So, armed with a three page document detailing the process, rolls of background cloth hastily secured from the haberdasher’s and some 3D scales which were specially commissioned (but which do not fold, so are rather awkward to carry) we stand on the platform awaiting our train to London. Some of us are preoccupied with the cold (mostly our southern European friends, our Siberian companion seems less impressed), but the only question on my mind is: will the process work in London as it did in the training lab? We have not been able to see the place where we will be working and do not know how quickly we can get the pots from where they are stored to where we can photograph them…

At the museum stores, we are met by Fiona Seeley, Head of Finds and Conservation at Museum of London Archaeology, who is going to tell us what pottery we are photographing, and Nicola Fyfe, the Archive Officer at the Museum of London, who will bring us the actual vessels from the shelves on which they are stored. We cannot grab the vessels from the shelves ourselves, for fear of mixing them up or damaging them, so Nicola brings over trays of vessels for us to photograph, taking away the ones we have already done. While some waiting is inevitable, this process runs surprisingly smoothly!

The reality of working with archaeological material is, however, a bit of a shock to our mathematicians. ‘Archaeologically complete’ means that a vessel’s profile can be fully reconstructed. Mathematicians tend to use ‘complete’ in the every day sense of, well, complete… This is something that we archaeologists failed to prepare them for. Although, to be fair, most of us did not know the state of the material that we would be photographing.

An archaeologically complete cup

The, sometimes, fragmentary nature of the vessels meant that occasionally we had to improvise when taking photos. I never thought I would one day be a hand model (albeit an archaeological hand model…)

Archaeological handmodelling, reproduced with permission from Museum of London

After three days virtually without daylight, we return to Leicester with an enormous load of photographs (13508 photos of 384 vessels), but at that time more questions than answers. How useful are these photos for training our AI? How can we combine these photos of whole vessels with future photos of sherds? What day is it?

Looking back at the session I can draw some conclusions from our first trip:

-

- As a pilot session, this was very informative indeed, if only for the planning of the process. We could get some very interesting results from training the AI with the photos we have taken, but even if we do not, then the planning of future photography sessions will be much improved by the experience of this one.

- A three-page document is nowhere near enough to get people to do the same thing. Almost immediately in the process, there were questions about how to actually implement the protocol, even between the people who designed the process. The number of photos taken per vessel ranged from around 25 (which is the number we indicated as a guideline in the protocol) to over 80 from a particularly enthusiastic photographer (you know who you are). So the old adage was proved correct: the first casualty of the war is the plan.

- Naming and annotating 13500 photos is very time-consuming. A clever solution is needed here.

- We need to carefully prepare anyone who works with us for what they will actually be working with. I would not like to shock more people as we shocked our mathematicians with our ‘whole’ vessels.

- If the camaraderie of this session is an indication of what future sessions will be like, I am very happy to embark on many more!

Subscribe to Daan van Helden's posts

Subscribe to Daan van Helden's posts

Recent Comments