Daring Deeds of Valour

By Dr Rachel Bates, University of Leicester

The 29 January 2016 marks the 160th anniversary of the Victoria Cross, a key legacy of the Crimean War (1854-56). Over the past four years, I have been looking at how the Crimean War shaped British understanding of war, violence and nationhood. The creation of the Victoria Cross in many ways encapsulates these overlapping themes. Here I take a look at the politics of the award and the work it performed for the British Army’s public image in the wake of the Crimean War.

The institution of the Victoria Cross on 29 January 1856 was realised by Prince Albert, though the idea of having a new military award had been proposed by the Duke of Newcastle a year previously. Both saw the benefits of rewarding individual valour, as opposed to specific military engagements and campaigns. For Newcastle, under intense scrutiny as Secretary of State for War, the award had the potential to boost recruitment and counter the dominant image of the British soldier as a victim of mismanagement. The need for positive intervention became more pressing as the War continued. The second half of the War is marked by a collapse of government and waning interest in the military campaign. The press had celebrated to varying degrees the early field battles of Alma, Balaclava and Inkerman, but found little to rejoice in Britain’s failed assaults upon the forts of Sevastopol. A focus on individual deeds helped to alleviate the War’s military and strategic failures.

Prince Albert devised the Cross along egalitarian lines. Britain’s unlikely military ally, France, had established the Médaille Militaire in 1852 for heroism in the ranks, to complement the Legion d’Honor for officers. The Cross trumped the French system, as a medal open to and worn by officers and privates alike. Its inauguration was popular at home, the British press celebrating its ‘democratic’ status. In reality, the monarchy was opposed to changes to the Army’s strict hierarchy by allowing promotion from the ranks. The Cross was arguably a symbolic gesture that diverted attention from debates surrounding the Army’s purchase system, a system whereby wealth and status determined entry into the officer corps.

Awards were issued according to certain ideals of heroic conduct. The early awards are notable for promoting abstract notions of battle-field honour and recognising humanitarian efforts. The Illustrated London News marked the first medal ceremony in June 1857 with a four page spread. Its vignettes depict fearless attempts to gain tactical advantage, such as dangerous reconnaissance; efforts to guard military honour and property, such as defending the regimental colours or reclaiming British guns; and successful attempts to rescue injured or surrounded comrades at great personal risk. Saving of life accounted for a number of the 111 awards issued for service during the Crimean War.

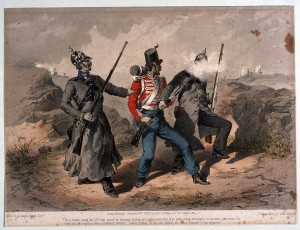

Rarely were singularly aggressive acts against the Russians celebrated as examples of martial prowess at this time. The case of Private McGuire, of the 33rd Regiment, illustrates this well. McGuire was taken prisoner whilst on sharpshooter duty but promptly escaped. According to the testimony of his commanding officer, Major George Mundy, McGuire noticed that the Russian on his right was carrying his firelock ‘very clumsily’ and so sprang forward, ‘wrested the firelock from him & shot him dead, then swung the firelock round’ and hit the other Russian in the stomach before re-joining his regiment. A print was released to commemorate the action, number eight in Lloyd’s series entitled ‘Incidents from the War in the Crimea’. It shows the point at which McGuire leapt between his assailants and shot his foe in the face.

M and N Hanhart after Michael Angelo Hayes, ‘By a sudden spring the 33rd man seized the Russians firelock’, 26 December 1854 (© National Army Museum)

This colourful print looks like a cartoon and the brutality of the act is also disguised by the discharge of smoke from the rifle, which conveniently obscures the face of the Russian victim. The description accompanying the print exhibits pride in the cool, routine nature of the act: ‘Calmly picking up his own Minnie, our friend returned to his regiment’. McGuire also received a gratuity of £5 from the Army for gallant conduct in the field. But the Queen and Prince Albert considered McGuire’s case of ‘doubtful morality’, since it encouraged people to kill rather than make their enemy prisoner. The Queen stepped-in to prevent McGuire from receiving the Cross. Instead, the public were presented with men who had taken Russian prisoners, or were captured as a result of helping comrades. The Queen was unwilling to be associated with acts that presented combat as anything other than an honourable pursuit. Defence rather than offense was a fitting criterion for royal recognition.

The inauguration of the Victoria Cross served not only key political objectives that helped boost public morale and maintain royal influence over the Army, it also helped to promote a better vision of war. A late-Victorian writer welcomed the Victoria Cross’ elevation of the British soldier and sailor, but here he goes on to grapple with the contradictions, complexities and passions of wartime endeavour:

‘It does seem an extraordinary comment on human nature, that, amid the clash of arms and the fury of battle, men can be bold as lions – aye, ferocious as tigers – one minute, and gentle as lambs – loving as women – the next, and are willing to sacrifice their own lives in their eagerness to save others, and to alleviate similar suffering in their comrades to that which they have done their best to cause in the heat of battle […]’

Further Reading

Alastair Massie, A Most Desperate Undertaking: The British Army in the Crimea 1854-56 (London: National Army Museum, 2003)

Jonathan Parry, The Politics of Patriotism: English Liberalism, National Identity and Europe 1830-1886 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Melvin Smith, Awarded for Valour: A History of the Victoria Cross and the Evolution of British Heroism (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008)

T.E. Toomey, Victoria Cross and How Won (London: Alfred Boot and Son, 1889)

Subscribe to Philip Shaw's posts

Subscribe to Philip Shaw's posts

Recent Comments