Michelle O’Reilly, Diane Levine, Neil Sinclair, and Sarah Adams

c

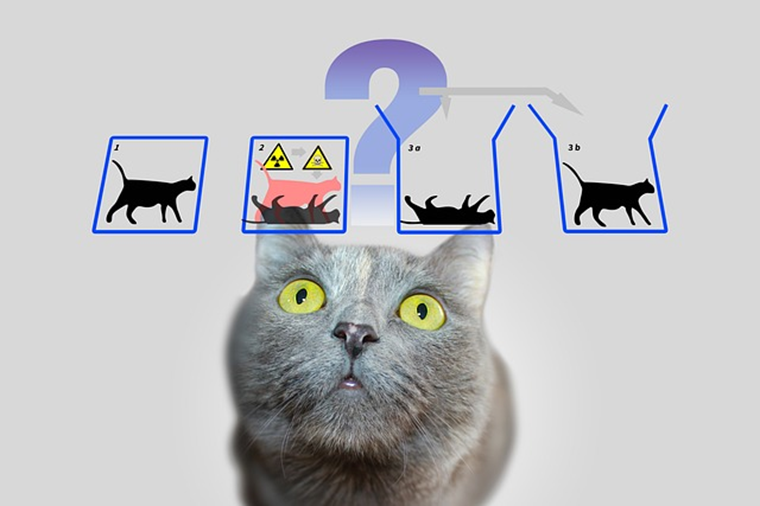

What if being kind online is harder not because children don’t care — but because they can’t see inside the box?

c

This was one of the most striking insights from our study [link to come] exploring empathy and digital behaviour among primary-age children. One child, grappling with the uncertainty of others’ emotions online, likened it to Schrödinger’s cat – the famous quantum thought experiment in which the cat’s fate remains unknown until the box is opened.

c

(Free image: Pixabay)

c

For these children, the “box” was the screen.

c

They recognised that in digital spaces, emotional cues are partial, ambiguous, or absent altogether. A message might say, “I’m fine,” but the person could be deeply upset. A silence in a group chat could mean anything: anger, sadness, or simply no signal. This masking of emotional effects and intentions doesn’t stop children from wanting to be kind, but it does make empathy much harder to act on with confidence.

c

If we want children to build healthy, respectful digital lives, our teaching needs to go beyond the basics of “be kind online” and grapple with the real emotional uncertainty that digital interaction introduces.

Here are four key takeaways for educators designing PSHE, RSHE and SEL curricula:

c

1. Teach empathy in a digital world as a process not just a value

Children in our study already believed kindness matters, but they struggled to read emotional cues online. PSHE lessons should unpack empathy as a skill, not just a virtue. Our study suggests that we need to teach children:

- That emotional cues online are different, limited, and open to misinterpretation.

- How to spot subtle signs of distress online (e.g. going quiet, short replies, sudden withdrawal).

- That empathy includes checking in, asking, and not assuming.

c

2. Help children understand the roles of intent and impact

The online world masks not only feelings but intentions, and that can open the door to misunderstandings. One message may seem playful to one person, and cruel to another. We need to support children to reflect on:

- The difference between what we meant and what someone experienced.

- How to take responsibility even when harm wasn’t intended.

- How digital spaces create ambiguity that needs careful navigation.

c

3. Make trust and authenticity part of everyday life online

Children in our study expressed uncertainty about whether others’ compliments were sincere or just “for show.” In a world of emojis, edits, and online performance, they questioned:

- What does it mean to be genuine online?

- Can you trust how someone says they feel?

Teaching digital citizenship should include reflection on authenticity, performativity, and trust, and how we build (or damage) it through digital habits.

c

4. Foster contextual empathy

Empathy doesn’t just happen in the moment. It relies on background knowledge of others’ lives and emotional worlds. The children who understood their friends best online were those who also knew them offline. PSHE should support students to:

- Ask questions about the context behind emotions.

- Recognise that different people respond differently to the same message.

- Reflect on why empathy feels easier with people we know well.

c

Final Thought: The Box Isn’t Empty

Our findings don’t suggest that empathy is impossible online. Rather, it’s harder, more complex, and more open to error, and this is precisely why it needs teaching.

Just like Schrödinger’s cat, children are trying to peer inside the box. It’s our job, in PSHE and RSHE, to help them open it.

c

Subscribe to ca270's posts

Subscribe to ca270's posts